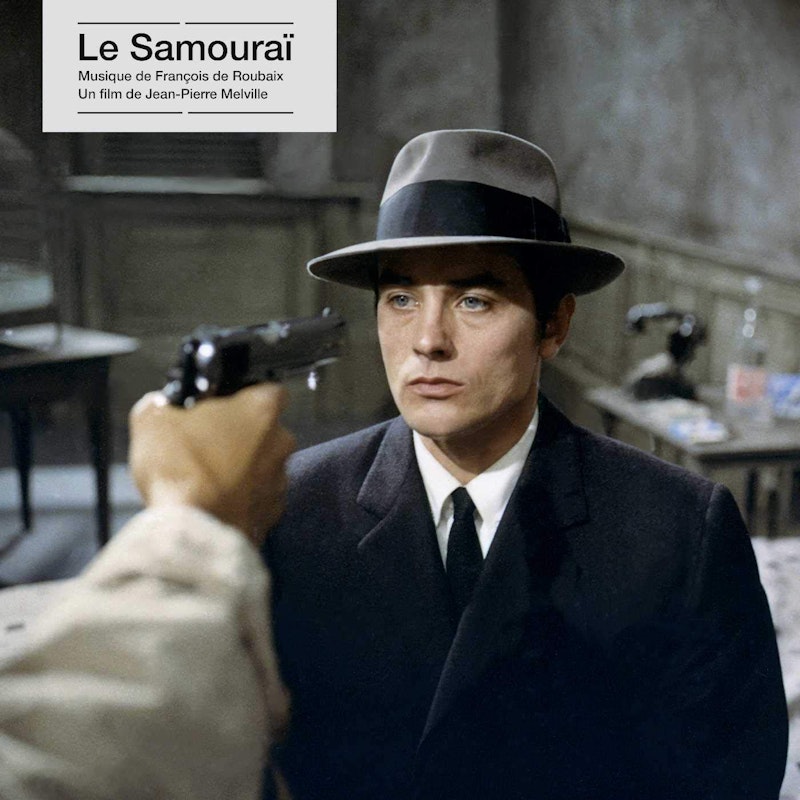

Nothing defines “cool” more than Alain Delon in Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le samouraï (1967). Yet there’s more beneath the surface of these cool, French waters. Le samouraï is an unusual film. While it’s an homage to film noir and especially American films of such genre, it maintains its own cinematic identity, mainly from Melville’s aesthetically slow cinematography, and the uniqueness and essence of Delon.

Delon plays a professional hitman, Jef Costello. As the film opens, we see a dark, gray-blue room in a dilapidated Parisian apartment. Everything’s still until we recognize a man’s body (Delon) moving on the bed. There’s also a bird in a cage, oddly out of place, chirping away, unaware of Costello’s life. He gets up, puts on his trench coat and his fedora, and with an elegance that’s at odds with the ruinous and slummy apartment, leaves.

Everything about his moves is deliberate. He steals a car, and proceeds to take it to the garage, where a man changes the car plates. During this interaction, he also receives a gun. We still don’t know where he’s going or what he’s doing, but he establishes an alibi with a girlfriend. He drives the stolen car to a club, where cool sounds of jazz and shiny glasses of martinis dominate. Unlike Costello’s dumpy apartment, the club is an example of high class and wealth. But he’s not impressed. In fact, all of it is irrelevant to Costello.

Moving with a precision from room to room, Costello finds the owner of the club and shoots him. Before he does, the owner asks him who he is, but Costello doesn’t think that’s of any importance. He kills and leaves in the same deadpan and emotionless manner that he arrived. However, as he leaves the room in which the hit happened, he’s seen by the club’s jazz pianist, Valérie. This is where the film really begins because it’s at this point that the police treat Costello as their prime suspect.

Despite the fact that Costello has a solid alibi from his girlfriend, Jane, the police detective is running more on a gut feeling than evidence. After all, Costello has been cleared with the alibi from Jane; Valérie unequivocally stated that Costello is not the man that she saw leave the club owner’s room; and the gun has been thrown into the river. Yet the police detective is stubborn.

The police are always tailing Costello, and they bug his apartment. This turns out to be a failure because Costello finds the bug, and the only thing that the police managed to record is Costello’s bird, chirping away. The plot continues to unfold as most noir or detective films do. In this case, Le samouraï isn’t unique, but Melville creates existential layers around Costello that only Delon can bring out.

Much like the torn wallpaper in Costello’s apartment, Melville peels back more layers and reveals interior aspects of Costello. Film director’s signs matter greatly, and in Melville’s case especially. Costello may live in an apartment that’s about to crumble, but he has glass bottles of mineral or spring water, neatly placed in order, on top of his cabinet. His suits and his fedora are impeccable. His wristwatch sits tightly around his wrist but with watch hands facing down. Costello is very particular about this appearance and how he executes his work, if we can call it that.

And then there’s the bird. Why would a hitman own a bird, especially one that has to worry about being caught? Costello clearly cares for it: he feeds it, gives it water, and even gives a small indication of warmth toward this creature, despite its annoying sounds. But the bird is, in many ways, Costello’s attempt at relating to another being. After all, he lives alone, and one can suspect that hitmen don’t make for good partners.

Every film has a mood, but Melville’s vision here is exceptional. This is a minimalist film but strangely, not nihilistic. Jazz permeates the screen; everything is gray, except for Valerie’s apartment; most characters aren’t showing a lot of emotion; and the plot movement is slow, bordering on oppressive. We watch the film unfold through unbearably thick grayness. This grayness may share its coloring with Jacques Tati’s Playtime (1967), where it’s used comedically and playfully to show the absurdity of modern life, but Melville’s grayness feels like there’s no exit out of existence’s oppression.

Delon’s performance is superb. His attractiveness is suspended, and Delon becomes Costello. Yet again, Delon’s gifts as an actor are on full display. He doesn’t smile at all; he’s cold and calculating as any hitman would be, but there is an existential quality to Delon’s performance. It’s as if we’re watching Delon play a stoic philosopher who happens to be a hitman too, but maybe has read Albert Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus. This is how his life appears to be—a man cursed to repeat the same action, namely murder.

How can such a man be moral? Is there anything in Costello that indicates that he’s good? The end of the film appears to lean in that direction. He has been paid to kill the jazz pianist, Valérie, but it turns out his gun had no bullets. He never intended to kill her, and thus he has in some way either sacrificed himself or committed suicide (I use the idea of suicide here in very loosely).

No matter what the answer may be on his morality, we must admit that Costello has been eluding everything and everybody. We can assume that he has been doing this for most of his life. So, where can this escape lead, especially given Costello’s lack of unity in life? In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus writes, “In the face of… contradictions and obscurities must we conclude that there is no relationship between the opinion one has about life and the act one commits to leave it?... In a man’s attachment to life there is something stronger than all the ills in the world… We get into the habit of living before acquiring the habit of thinking. In that race which daily hastens us toward death, the body maintains its irreparable lead.”

Costello’s a man who has the habit of thinking, but what kind? When he faces one of the people who hired him to kill the club owner, Costello is monotone and blunt, looking at him with piercingly cold, blue eyes.

“Nothing to say?” says the blond gangster.

“Not with a gun on me,” says Costello.

“Is that a principle?”

“A habit,” replies Costello.

It’s the habit of being a hitman that eventually leads to his death, but perhaps, for Costello, it was, to use Camus’ own words, “a happy death” after all.