Around 30 years ago, still in my mid-teens, I watched a movie on late-night TV called Dark Star. It was a science-fiction film set hundreds of years in the future on board a spaceship, which was the sort of story I liked. Dark Star, though, bored and annoyed me.

It was slow, erratic, and cheap-looking. It felt like a movie for potheads, with no strong central plot idea or characters with a strong reason to do anything. In the years since, I’ve come to suspect I was too harsh, and so was eager to watch it again as part of Criterion’s 1970s science-fiction collection. And I did like it more than I did the first time around. But I don’t think I was wrong about the pothead angle.

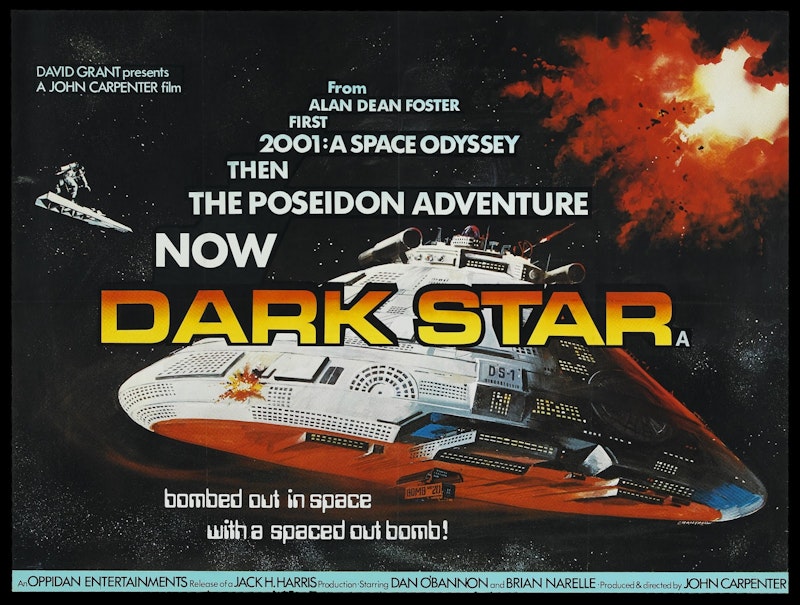

The movie’s got an interesting background, at least. It started out as a student film, directed by a young John Carpenter from a script he wrote with Dan O’Bannon, who’d go on to write Alien, work on special effects for Star Wars, and write and direct The Return of the Living Dead. They borrowed their ending from a Ray Bradbury story (“Kaleidoscope”), and shot the movie between 1970 and 1972. They then worked with at least one distributor—accounts vary—who insisted on additions to bring the movie up to feature length.

The movie follows the four-man crew of the Dark Star, a spaceship whose job is to go to “unstable: planets that might threaten future colonization of yet other planets, and destroy them with exponential thermostellar devices—planet-busting bombs equipped with artificial intelligence. It’s been a long mission, though, and the crew’s past the point of getting on each other’s nerves. One man (Dre Pahich) spends all his time alone in the ship’s observation bubble, watching deep space. Another (Dan O’Bannon) has captured an alien for a pet. Another (Cal Kuniholm) likes playing with an emergency laser weapon. Then there’s a storm in space, the ship’s hit, and things go wrong. Even the original commander of the ship (Joe Saunders, voiced by John Carpenter), dead and kept in suspended animation, can’t help.

The story’s aimless, as we get bits of character detail at random, interspersed with things like an extended sequence of the pet alien getting loose. That sequence attempts slapstick comedy without much success; O’Bannon, watching audiences not laugh at an alien hiding on board a spaceship and ambushing a crew member, decided that if the idea didn’t work as comedy it might do better as horror. It turns out he was right, but that doesn’t help here. In addition to lacking much of a comic sense of timing, the scene has no obvious relevance to story or character.

In a real way, though, that apparent lack of structure brings out the point of the film. It’s about four men stuck together in an environment they can’t get out of, doing a boring job. The lack of coherency reflects the way they’re disintegrating under the tedium. The feel of life on the Dark Star is very strong, and it fits with the glimpses we get of the broader society behind the mission.

Specifically, the ship’s mission of destroying entire planets that might get in the way of later colonization has an obvious political subtext. The massive bombing campaigns of the Vietnam War were still in the news. What the movie successfully brings out is the lack of moral sense on the part of the bombers. Nobody on the ship cares about the places they bomb. The mind-boggling tedium of day-to-day shipboard routine has left them alienated from the wider universe.

Occasionally, there are moments where we see more depth in some of the characters. Pinback, the man who took the alien pet, keeps a video diary in which he makes a surprising revelation. Talby, who almost lives in the observation dome, does so because of a near-spiritual fascination with space. These moments are the real heart of the film, developing the characters so that the ending turns out to be a coherent ending to something like a set of arcs.

The overall effect’s distinctive. It’s interesting in ways more conventional stories aren’t, while also feeling shapeless. There’s a lack of anything resembling narrative momentum from scene to scene, but not every story needs that kind of momentum. Dark Star is a series of character studies, tied off with a surprisingly effective conclusion—one that takes a dark turn precisely because a character refuses to accept that there exists a world outside of their senses, and abandons himself to the alienation.

Beyond the sense of character, there’s also a sense of parody to Dark Star. Not just a social satire, it also takes the piss out of traditional science fiction. A number of writers have seen it as a reaction to 2001, complete with a pseudo-transcendent conclusion, but it strikes me as more of a response to Star Trek: a navy ship in deep space, seeking out brave new worlds and bombing the hell out of them. Behind Trek there’s a tradition of semi-militaristic and at least semi-colonialist science-fiction going back to editor John W. Campbell and his Astounding magazine; Dark Star sends up the idea of an elite military crew driven by idealism.

It’s worth noting one of Carpenter’s best-known later films is his adaptation of Campbell’s “Who Goes There” as The Thing. Still, Dark Star is more of a piece with the New Wave of science-fiction writers, people like Michael Moorcock, Harlan Ellison, and Samuel Delany. It also points ahead to something like The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, a story abut scruffy outsiders knocking about inhabited space; a picaresque space opera. Dark Star is one of the first films to imagine a galaxy of planets visited not by a perfectly-regimented gleaming military force or an idealistic agent of justice, but by a ramshackle group of cynics, the kind of people whose supply of toilet paper was lost when a storage area accidentally self-destructed. You could even argue there was a distant influence on the outcast rebels of the first Star Wars.

Science fiction can be used in a lot of different ways. It’s often plot-oriented, but doesn’t have to be. Dark Star’s not a complete success, but it shows how flexible the genre is. It’s worth watching. It has moments of real wit, even if it also has long sequences of tedium, and a strong ending that pays off an unusual sense of character. It’s not the greatest science fiction film of the 1970s, but it’s one of the more interesting.