Liberty has always been a fluid and versatile concept, and remains so today. Few ideas inspire so much devotion, few ideals so much pragmatism. However, when projected onto to the world of individuals, liberty wears 1000 faces. History demonstrates the evolving nature of liberty, even in broad social terms. As history doesn’t proceed by consensus, it behooves us to consider what meaning of liberty we’ve adopted in our own value systems, and how others understand it. Historical examples of the evolving nature of liberty can offer at least some scope for that consideration.

Libertas referred in Roman law to freedom opposed both to the state of slavery and to the power of magistrates. The idea of liberty bound the community by legal definitions and procedures, which formalized the interactions between individual and state. Libertas among the elite contained other, more humanistic ideals as well, including equality (amongst the aristocracy, at least) and a shared opposition to monarchy in any form. It stemmed from a shared ideal of competitive politics and traditional authority of the Senate. These republican elite values expressed themselves in Roman politics, and through the mechanisms of democracy became the values of the Roman people.

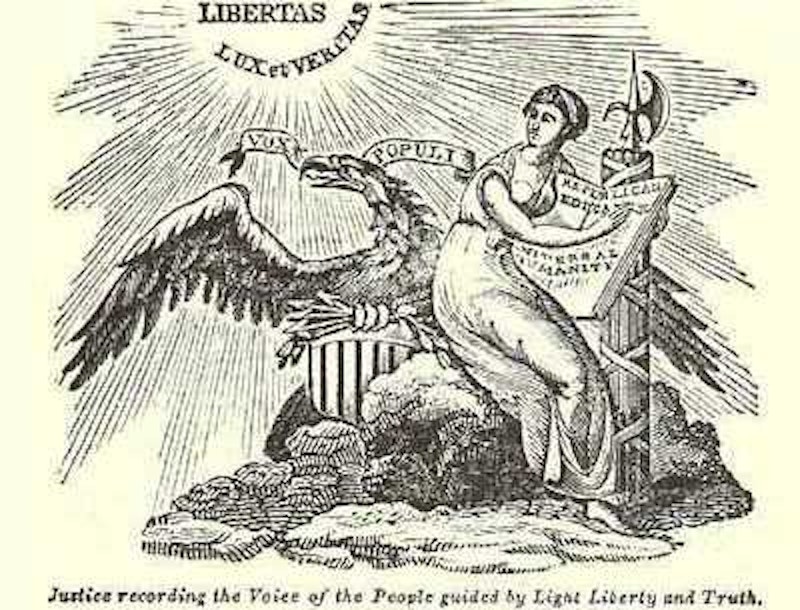

From a foundational and concrete legal principle in Roman democracy, defining as it did the fundamental and inalienable rights of every citizen, broader, less empirical standards emerge within the concept of liberty. The public worship of Libertas, both as a goddess and an aspect of Jupiter, reveals the powerful emotions that the idea could inspire, or be made to inspire. Likewise, the U.S. Constitution lays out our country’s supreme law, not its values, but New York’s Statue of Liberty evokes similarly stirring impressions on some who view it. But American love of liberty is most evident at election time.

Of course, one wonders how deeply Romans ever actually maintained these values. Hundreds of thousands in Rome and throughout Italy were ready to bend the knee when Caesar presented himself as dictator. Caesar was murdered on the floor of the senate by a cabal of hoary old men, but the Senate confirmed his successor’s creeping hegemony a generation later. For the most part, the Populus Romanus, model of American civil society, saw Romans looking to their own self-interest throughout the century of bloodshed that squandered the Republic. I don’t blame them.

As society descended into civil violence two millennia ago, leaders rallied their followers around traditional ideas: the rights of a free People, nostalgic moral codes, and the abomination of tyranny. The shattered Republic was re-forged into a hereditary monarchy under the same watchwords. Though their authority was essentially unlimited, Roman emperors minted coins featuring images of Libertas and bearing inscriptions testifying to the meaningless sanction of a Senate both rotten and impotent.

The concept of liberty has always been slippery, serving the purposes of those who use it to persuade.

Traditionally, liberty has been regarded as an inherently social value. In America’s history, liberty has often stood close with national independence and sovereignty, witnessed by the patriotism inspired by the word, its symbols, and its rituals. In more recent decades, our society has largely replaced that idea with a concept of liberty primarily experienced and understood in a personal and purely subjective mode. Instead of a definite, specific, and constitutionally guaranteed aspect of citizenship, Americans today demand and dispute the liberties inherent in and endowed by human nature itself.

Fundamental differences in how liberty is understood doom ideological compromise or reconciliation in many cases. For instance, the emotionally laden issues of individual freedom that lie at the heart of the battle between pro-choice and religious disputants obscure the many health, ethical, and other considerations that ought to frame any deliberation regarding the legality of abortion. But these crusaders don’t burn with a fire for reasonable regulation, they’re transported by a social or theological ideal. On one side (speaking broadly) stands an anti-authoritarian rejection of the power of government, men, or others to restrict a woman’s choice and behavior. On the other stands commitment to an idea of humanity in which some acts represent an intolerable violation of absolute law, which requires the restriction of individual liberties by the authority of the state. In both cases the scope of one’s legal freedom to do as we like is derived from and describes an ideal of more basic relationships between independence and authority.

In American culture today, we typically regard liberty as the freedom to, rather than the freedom from. The ideals represented by contemporary conceptions of liberty are valued so dearly by many that they stand ready to defend their idea of it on college campuses, in their bunkers, and in the nation’s courtrooms.

Are these or other definitions and ideals of liberty less valid for standing outside the historical mainstream? We cannot deny their emotional power. The validity of one conception of liberty or another requires a value judgment, obvious to all, if only because we are now judging entirely according to our own standards. Ancient Romans wouldn’t have understood some of our ideas of liberty, but that doesn’t diminish their power to move us as individuals. Moreover, conservatives may moralize that a selfish conception of liberty is wrong in itself, or progressives that a purely legal conception is too narrow; such criticisms only confirm that the idea of liberty is subject to reformulation, and that most of us living in a democracy feel some urgency toward these ideas.

Our individualistic, emotional conceptions of liberty render us susceptible to manipulation. By tapping into our basic and unqualified beliefs, the wielders of power and shapers of conviction can inspire an extraordinarily zealous enthusiasm for the idea of liberty. Only by the defense and exercise of your liberties, or in the denial and inadequacies of your liberties, can you truly be said to know what it is to be an American, we’re led to believe. Americans venerate Libertas, each of them by another name.

At times the rhetoric of the inspired ones outruns the logic. When Charlton Heston magnificently snarled “from my cold, dead hands,” he appealed not to “law abiding” citizens, but to those who will defy the state to protect the status quo. The depth of the conviction, though, is obvious. For most of us living in a free society, liberty emanates from some profound truth about the human condition, or some essential relation between the individual and society.

Given that American society tolerates the expression of differences of opinion, various conceptions of liberty derived from personal conviction and practice (e.g. egalitarianism, meritocracy, religious freedom) inevitably conflict with one another. The idea of liberty stands at the center of American self-image. The public institutions many value most are those that preserve it, as they understand it.

Any attempted general description of liberty should include a balance of rights and responsibilities. The most emotionally appealing, however, are those that reduce the concept to an elemental level.

For all the efforts of those who rally their partisans behind the idea, it’s not possible to finally define liberty within a free society, much less to impose a definition on history. A democracy’s ideals require new formulations of the concept of liberty to reflect changing attitudes of individuals. The mechanisms of democratic government provide a means for citizens to project a view of liberty onto society.

As individuals, we all apply the concept of liberty differently to suit our various purposes, as do those who seek to prey upon our emotions for their own gain. In the mouths of our country’s leaders, liberty and associated ideas are often meaningless; worse, it often serves as a slogan legitimizing views of an antithetical, unconstitutional, and anti-social nature.

If we seek to wrestle with our beliefs and understand one another as Americans we ought to clarify the range of our ideas regarding liberty. To the extent that Americans still value our liberty, we need to examine the origins, foundations, and nuances of our ideas regarding liberty before the threats facing it deprive us of the values we claim to cherish and defend.