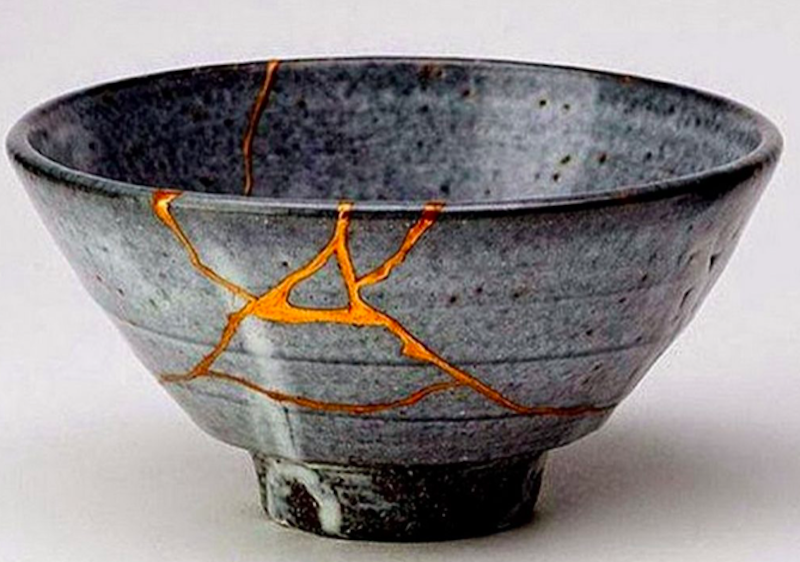

The other day, the wind on my lanai blew a coffee cup I liked off of a table, shattering it. I did what most people would—picked up the pieces and threw them in the garbage can. There are people in Japan, however, who would've handled the breakage differently. They'd have glued the pieces back together with golden lacquer, following an ancient practice known as kintsugi, an expression of the elegant Japanese aesthetic philosophy known as wabi-sabi. The damaged cup would've taken a new kind of beauty—one that spoke of the impermanence of life in general. One can own a beautiful object that, in a moment, is shattered, just as one can have a beloved friend or relative who loses their life in an instant.

Americans live in a disposable society. We replace anything damaged even slightly because we can only accept perfection. If we thought in the wabi-sabi way, we'd embrace imperfection, allowing us to view something that could be considered decrepit in our sleek, mass-production culture as having a singular beauty.

Wabi-sabi, an outgrowth of Buddhist teachings, merges two Japanese concepts into a unique blend. There’s no direct equivalent of the word wabi in English. "Rustic" is probably the nearest equivalent, but it comes up short. The word originally referred to the loneliness of living in nature, remote from society, but its meaning has evolved over time, taking on less melancholy connotations. "Flawed beauty" is what it refers to now. Sabi expresses the effect that time has on objects. A rusted old metal wall exhibits sabi. Nobody would build a rusted wall, but it's still possible to see the aesthetic value in one.

Consolidating the two words into wabi-sabi expresses an aesthetic based on the appreciation of aging, flawed objects, and finding beauty in simplicity. It's about celebrating the way things are rather than how they should be. An object exhibiting wabi-sabi has the quality of inevitability—time changes everything. Maintaining a perfect look is impossible over the passage of time, and it's not something to be sought after. If people could accept this about themselves, they'd be happier and would save money. But the Kardashians and Instagram set our shallow cultural tone at this time, and they're about as un-wabi-sabi as possible.

The concept of wabi-sabi, the rough Japanese equivalent of the Greek ideals of beauty and perfection, has been at the core of Japanese artistic expression for centuries, but walk around Tokyo asking random people to define the word, and you'll find many struggle with the task. Someone might eventually say that wabi-sabi refers to the "soul" of Japan, which is concise and accurate, yet not quite a definition. Most Japanese know wabi-sabi when they see it, but explaining it's another matter. How many Americans could, on the spot, explain what Americana is, and how it's reflected in this nation's music, cinema, fiction, folklore, and material culture?

The West is obsessed with symmetry and perfect proportions. Murata Jukō, founder of the modern Japanese tea ceremony, saw too much flawless beauty in the aristocratic manner in which the tea ceremony was conducted in 15th-century Japan. He was dismayed that the shoguns were holding the ceremony in gaudy surroundings to show off expensive vessels and utensils imported from China, which was a deviation from the practice's spiritual roots. Jukō's redesign of the ceremony was in keeping with the tenets of wabi-sabi. At the time, tea ceremonies were held on balconies during a full moon. Jukō wanted it to happen while the subtle interplay of shadows during a half-moon, or a partially-clouded moon, and he wanted to replace the fancy imported products with rustic, imperfect objects made by Japanese artisans. To this day, the tea ceremony remains one of the most pervasive manifestations of the wabi-sabi philosophy.

Wabi-sabi is under enormous pressure in Japan from the consumerist values of the West. Around 45 percent of Japanese women own a Louis Vuitton handbag, an item representing the Western obsession with symmetry and perfection. The Japanese are obsessed with prestigious brand names, which is antithetical to wabi-sabi. Prestige has no place in the wabi-sabi aesthetic.

As for American culture, it's about material possessions and bling. Nobody can be too rich, too young, or too fit. The pursuit of perfection comes with a price—depression, anxiety, drug addiction, and burn-out. Advertisers stoke this culture by encouraging us to seek unattainable goals, which is exhausting and unnatural. It's also dangerous to one's mental health. Striving to live a life of perfection ultimately means that all it takes is a little hiccup to take you down. It gives people a brittle quality that those able to find satisfaction with their current circumstances don't have.