I played a lot of Magic: The Gathering as a teenager, with the occasional relapse since then. I always enjoyed the atmosphere and aesthetic of the artwork more than the actual game. This is especially true of the older sets that pre-date the makeover in the early-2000s. I liked hanging out at the gaming store and sifting through the loose cards, the rejects left behind by “serious” advanced players.

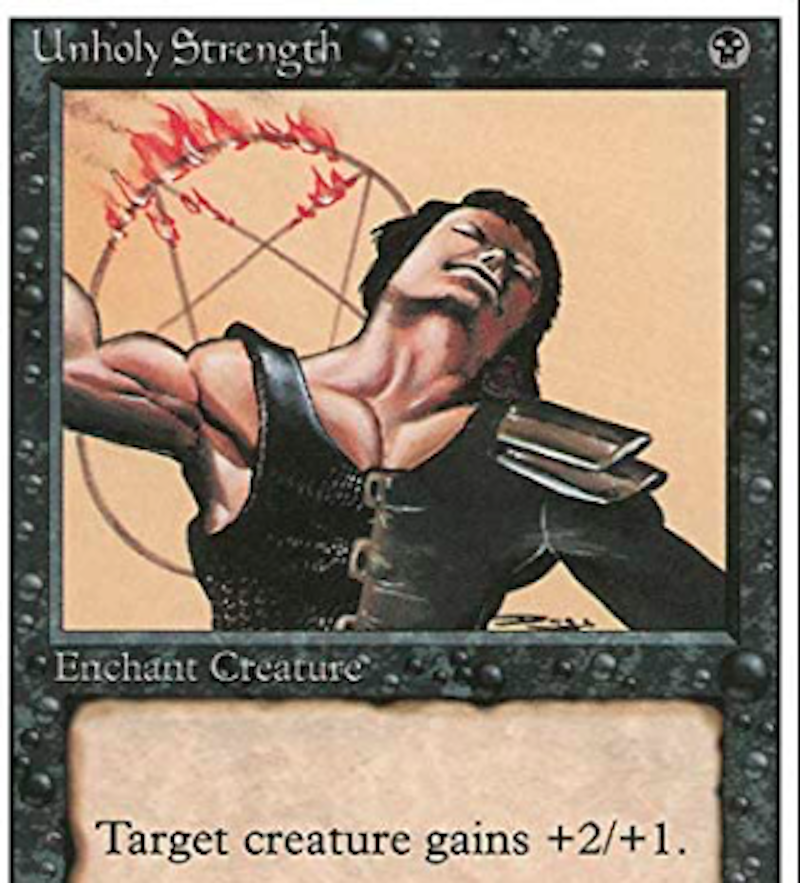

One day, I happened upon a version of a card called “Unholy Strength.” The version most people had contained a simple illustration of an armored man set against a yellow background, seemingly writhing in ecstasy. This version was different. This was the infamous original that featured a flaming pentagram in the background. Wizards of the Coast amended this in future print runs, in a move that must’ve been to appease religious and parent-led organizations. In a perverse irony, the card actually looks far more suggestive without the obvious pentagram, beckoning the imagination to wonder what’s going on outside the frame.

Magic: The Gathering is an interesting cultural institution, emerging in 1993 in the dying days of the “Satanic Panic.” This was a time of hysteria around supposed child abduction, torture and sacrifice. Beginning in the early-1980s with the release of the book, Michelle Remembers, the events stretching into the mid-1990s reflected the anxieties and insecurities of an America emerging from Vietnam, Watergate, urban decay, secularization and the sexual revolution. This coincided with the steady rise in divorce rates, two-income households, deindustrialization, and a retrenchment of tensions with the Soviet Union. The emergence of televangelism and the prosperity gospel was no accident.

The Satanic Panic thus gave a face to the suspicions people felt about schools, daycare facilities and pop culture, thus these institutions became the primary targets for sensationalism. Accusations were leveled against care workers, teachers, musicians, authors and filmmakers. Shows like 20/20 and television hosts like Geraldo Rivera and Oprah Winfrey aired TV segments like "Satanic Cults and Children" and "Devil Worship: Exploring Satan's Underground." Concepts such as “recovered memories” and “baby breeders” entered the cultural lexicon. It was all nonsense. A lot of innocent people had their lives ruined, careers destroyed, or went to jail. Many of the victims were working-class people who suffered for the insecurities of the emerging professional class. It was an abomination of justice.

But by the early-1990s, the panic started to fade. In 1992, the FBI released a report that thoroughly discredited the satanic ritual abuse scare. Testimonies were recanted, damages awarded, and apologies began. To Geraldo’s credit, he was one of the few boosters of the hysteria who apologized in 1995:

"I want to announce publicly that as a firm believer of the 'Believe The Children' movement of the 1980's, that started with the McMartin trials in CA, but NOW I am convinced that I was terribly wrong... and many innocent people were convicted and went to prison as a result... AND I am equally positive [that the] 'Repressed Memory Therapy Movement' is also a bunch of CRAP..."

Geraldo’s remarks bear an eerie echo of the Salem Witch Trials of the 1600s in New England, after which the the jury declared in 1697:

“And do hereby declare that we justly fear that we were sadly deluded and mistaken, for which we are much disquieted and distressed in our minds, and do therefore humbly beg forgiveness, first of God for Christ's sake for this our error. And pray that God would not impute the guilt of it to ourselves nor others. And we also pray that we may be considered candidly and aright by the living sufferers as being then under the power of a strong and general delusion, utterly unacquainted with and not experienced in matters of that nature.”

It wasn’t the thoughts and feelings of Massachusetts Bay denizens that allowed the injustice of the witch trials to take hold. As Nathaniel Hawthorne noted in The House of the Seven Gables, it was in fact:

“the influential classes, and those who take upon themselves to be leaders of the people, are fully liable to all the passionate error that has ever characterized the maddest mob. Clergymen, judges, statesmen—the wisest, calmest, holiest persons of their day stood in the inner circle round about the gallows, loudest to applaud the work of blood, latest to confess themselves miserably deceived.”

Comparable events took place in France around the same time, as described by Aldous Huxley in The Devils Of Loudun. At the center of the story is the persecuted priest, Urbain Grandier. What was his real error? Was it his sexual affairs with the widows of his parish? Did he have a secret pact with the Devil that he used to possess the nuns of Loudun? No. In fact, he was initially acquitted on these charges. His real mistake was speaking out publicly against Cardinal Richelieu, one of the premiere do-not-cross figures of history. It could only go one way from there for Grandier: convicted in a new show trial, tortured and burned alive.

Huxley also provides us with a view into how the witch hunter so often manifests the very evil he or she claims to fight:

“No man can concentrate his attention upon evil, or even upon the idea of evil, and remain unaffected. To be more against the devil than for God is exceedingly dangerous. Every crusader is apt to go mad. He is haunted by the wickedness which he attributes to his enemies; it becomes in some sort a part of him.

Possession is more often secular than supernatural. Men are possessed by their thoughts of a hated person, a hated class, race or nation. At the present time the destinies of the world are in the hands of self-made demoniacs—of men who are possessed by, and who manifest, the evil they have chosen to see in others.”

Huxley describes how the afflicted witches, encouraged or even coerced into thinking themselves possessed, acted out their own possession in a fit of mass hypnosis. Additionally, when you reify a concept and use it as a cudgel to attack a certain group or class, the attacked person may begin to positively identify with those concepts. The hateful identity becomes a source of out-group solidarity.

The Satanic Panic presents us with a wealth of examples. With “Satanism” used as a cultural weapon of powerful interests and suburban polite society, those with a mind for dissent and transgression began to wield it for themselves. A lot of ink has been spilled by commentators about the PMRC, Ozzy Osbourne eating a bat, and other tired stories of “rock under siege.” But this is the least of it. The wider cultural milieu helped inspire even more radical and extreme forms of expression that flouted the pieties of the moral crusaders.

The most prominent example is probably Florida’s Deicide, a band whose blasphemous message and terrifying music went further than even Venom, Slayer or Possessed had years earlier. Another is Morbid Angel, whose 1993 masterwork, Covenant, was inspired by and dedicated to the same Urbain Grandier from Huxley’s book. This cultural radicalism reached its apogee in the series of church burnings perpetrated by black metal devotees in Norway, Poland and elsewhere in the early-90s.

Notable as this was, it did nothing to bring the hysteria of the Satanic Panic to an end. After all, outright Satanic art and “activism,” no matter how oppositional and iconoclastic, fits comfortably into a Christian moral paradigm and relies on it for its potency. Deicide frequently drew the ire of Bob Larson, the author and televangelist known as an “exorciser of demons,” leading to a near confrontation at a show in 1992. But far from being able to “take one another out,” the two sides justify each other’s existence until the cultural ground shifts beneath them.

Unfortunately, moral panics are also uniquely resilient against truth-telling and debunking efforts. Debbie Nathan, writing for The Village Voice, reported on the Satanic Panic and exposed it for the farce that it was. In her 1990 article, “The Ritual Sex Abuse Hoax,” she describes how “many parents were skeptical, but therapists told doubters that unless they believed the allegations, their children would be further traumatized” and that “prosecutors, police, and social workers were attending nationwide conferences” extolling the threat posed by the Satanic menace. But it takes more than a few writers with integrity to bring the edifice crashing down.

The Satanic Panic ended because people wielded institutional power against it through litigation, to the point where the FBI got involved. In addition, the cultural concerns of 1995 had shifted since 1980. Through the remainder of the 1990s and into the 2000s, more cases were dropped and alleged victims of ritual abuse came forward to recant. The final coda can probably be dated to 2011, when the West Memphis Three were freed on an Alford plea when new DNA evidence called their 1994 convictions into question.

By 2011, the warriors on various fronts had moved on, many of them becoming isolated cultural curiosities or falling into obscurity. At that point, Deicide could play “When Satan Rules His World” at a rented-out church annex and no one would bat an eye. Magic: The Gathering began to reincorporate demonic creatures into its universe. Televangelists and other Bible-thumping scavengers of the “moral majority” were little more than a punchline outside of the most conservative and insular Christian communities.

The events of the 1980s and early-90s rarely came up in conversation, and any sort of moralizing impulse was at its absolute nadir in 2011. Like the late-1970s, this was a relatively easygoing time when it came to social issues, most of the relevant energy bound up in the fight for marriage equality. Other fights seemed to be resolved, or at least in a state of detente. Comedians could make off-color jokes on Twitter or at Comedy Central Roasts with impunity. Cards Against Humanity, released in May 2011, was the transgressive party game of choice among bourgeois liberals. There was a playfulness around issues of identity, and whatever third rails existed were clear and easy to avoid.

Things have gone downhill since 2013, a rolling series of moral panics, tearing through academia, journalism, the workplace, government, cultural spaces, and dividing friendships and turning family members against each other. Every time we think “maybe it’s over,” a new outrage explodes across social media and we’re at each other’s throats again.

This time will pass, like other moral panics. Even now, the arrival of a new administration in the United States signals a decline in cable news ratings, less online engagement with political news, and the fading of “The Resistance™” from the cultural chessboard. There are at least a few pressure points that will see some relief in the near future.

But I’m not so naive to think everything will suddenly calm down. Rather, our current cultural turmoil is exiting its revolutionary phase and entering institutionalization. This can seem scary. But nothing dilutes the energy of a movement like the integration into old, existing institutions. The players will no longer be obscured within a large, diffuse, amorphous cloud of “activism.” They’ll be in positions of elected office or bureaucratic appointments. You’ll know who to blame. The “rules” and boundaries will solidify, as will methods and avenues of subversion. But there are still a lot of risks, and a lot of people eager to get their co-workers fired and lives destroyed for a sliver of clout.

This poses a difficult set of questions for dissidents, or anyone of genuine moral virtue. A professor once told me about the nature of virtue. Each virtue has its extreme, negative corollary. In this case, we’re talking about courage. Courage, taken too far, can become foolhardiness. At the Battle of Dyrrhachium in 1081, the Byzantine Emperor Alexios could’ve kept the Normans pinned down as they besieged the city. He could’ve used time to starve them out and force a withdrawal. But he instead pursued an aggressive assault, which led to a disastrous defeat. All the elan in the world won’t defeat a well-prepared enemy.

Likewise, all social movements, especially ones despised by the majority of people, don’t have time on their side. Since late 2014, various gadflies and culture warriors have emerged to try and fight the good fight. But they stare into the abyss for too long and flame out, suffering mental breakdowns or fleeing to what remains of the American right. They’ll tell you that you need to fight, make yourself known, and stand out among “the cowards” who say nothing. They’re wrong. They’re encouraging you to throw yourself into no man’s land alone, artillery and machine guns blazing.

Changing individual minds won’t fix this. It may give you a few more friends you can be honest with in private, but that’s not enough. You need to join with or build alternative institutions. You need to mount challenges in the courts. You need to do what you can and with whatever allies you have to change the economic dynamics. Or at the very least, if you’re going to go it alone, Commando-style, make sure you have enough “fuck-you money” on hand to not worry about the consequences.

But choose your fights wisely, preferably ones that will benefit you personally, socially or financially. Don’t be a fool, don’t become an unwitting asset in someone else’s activist portfolio. You do no favors by martyring yourself to provide a “noble example.” The best act of dissent is to glide through the storm, join the most important institution of all—the great mass of people who live their lives with quiet dignity and decency. We’ll need that institution to be as large and robust as possible when the fever finally breaks and it’s time to rebuild the other institutions.