Nobody went outside. No, they did, but it was a passage and that’s all. People lived indoors; and living so, they moved from one indoors to another. Top hats everywhere, rooms as seen on Masterpiece Theater. Wood panels, brass fittings. Gas lamps, brocade drapery, tablecloths. Crowded wallpaper and the top hats. Though the hats disappeared. People don’t wear hats indoors.

Here my thoughts ended. There remained a mere impression, but for decades this impression has pleasantly loomed or swelled in the back of my mind. It throws a light, one in which I feel that late-Victorian life is something I know. It isn’t, I don’t. Still, the feeling stays with me. At 13, I read a book called Portrait of Max and it gave me a dream of what life can be. By this point I’d given up on the avenues at hand. Classmates, my mother and father, brother, grandparents, teachers, my body—they’d all gone splat as far as building hopes was concerned. But adults said I was good at writing, and here was a writer who lived the way I hoped to live. I suppose that notion turned a dial on the whole thing. The vision’s glow or gravity was increased, and the vision came to live with me forever.

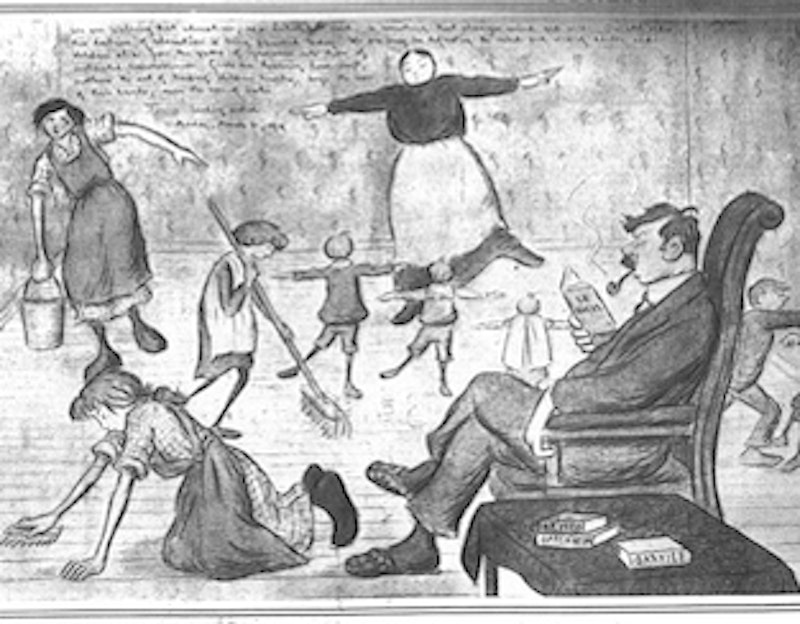

Portrait of Max is about Max Beerbohm, who wrote essays and drew cartoons. He died when Elvis was something new and Max was something very old, a relic visited by august names who honored him for... for his charm, really. He was treasured. This can shade into veneration, and saints can be winsome, as with Gandhi. But look at Gandhi’s life work and the winsomeness was merely an element. Whereas winsomeness was Max’s big thing: winsome and sharp, winsome and original, winsome and adroit. As with the work, the life: unpretentious and winsome, affable and winsome. S.N. Behrman, author of Portrait of Max, did a first-class job of presenting his man, and the picture was of a small angel who beguiled. Max’s fedora and china blue eyes were featured. He sang music hall songs (“When Max sang, he leaned far forward in his chair, his face immensely solemn”). Behrman also showed why this being was not just dear but wonderful.

Max’s conversation, as somehow reproduced without mention of tape recorder or notepad, was indeed perceptive and phrased like a series of small marvels. Consider Shaw and the back of his neck, which Max found “especially bleak—very long, untenanted, dead white.” This is probably the best use of “untenanted” ever. As a boy I was put away by the fake newspaper quotes (Behrman transcribed them) that Max had written into a book by Queen Victoria. For example: “Not a book to leave lying about on the drawing-room table nor one to place indiscriminately in the hands of young men and maidens... Will be engrossing to those of mature years.—Spectator.” I hadn’t read polite late Victorian book chat. Even so anyone could feel that a tone had been hit. Subconsciously I delighted at the thought of someone who could move from voice to voice, superior to all of them, and superior to the Queen and Bernard Shaw.

Yes, Beerbohm, a grown-up man, was cute. I minded this much less than might be expected of a 13-year-old boy. Nor did I mind the subtly apparent fact that the china-eyed Max had at most a nub of a sex life. Imagine that sacrifice for a boiling young creature of zits and lust in 1975. Yet I never felt it and the issue remained a wisp at most. Not until my 30s did I wonder if this figure from my long-ago might’ve been a particular way, just as gays are gay and heteros are straight, and that his way involved not feeling much interest in sex. Max, as a being, was comfortable for my 13-year-old self. The way he lived was comfortable. He lived indoors and knew people (Behrman’s book thronged with them), and this knowing took the form of experiencing anecdotes first-hand and drolly observing foibles. There were incident and variety—Oscar Wilde, Edward VII, and Frank Harris are highly distinct from each other, not to mention from humanity’s normal run—but there was little that was heavy, or at least not in Portrait. Not that the book’s a greeting card. It gives a sense that life passes and in doingsocan leave a bruise. But Max, at least in the book, was un-bruised. The life he passed, again per the book, was a model of a man being, in his particular way, splendid.

Some teenagers want a life with the heavy stuff: rebellion, vengeance, triumph, undying love. Or even just the medium stuff, like regular love. Looking back, I think I shied away from all that. Yet I wanted to live. Without knowing it I imagined a substitute: a life of happy, untroubled social busyness lit by my personal brains and charm. That was my picture of adulthood well spent. I didn’t have such a life then, and I never would. But that’s what I had in mind; that was what I was living toward, if all went well. I saw nothing else on the horizon. Now the horizon has come up close; it threatens to pass me by. The life I wanted still hasn’t arrived, and for reasons that have become obvious to me over the decades. My habits, my temperament, the shortcomings of my nervous system. If I’d been solid enough, perhaps I wouldn’t have fallen in love with Portrait’s low-gravity equivalent of adult life. But I was sprained inside and had to take things easy while longing for them very much.

None of this is Max’s fault, or even S.N. Behrman’s. Max describes the eyebrows of Arthur Wing Pinero, Victorian playwright: “The skins of some small mammal, don’t you know—just not large enough to be used for mats.” For all the murky reasons that I loved Max Beerbohm, I also had reasons like that. I was an early teenager with ragged t-shirts and spaniel hair, and I fussed over an Edwardian bell-lettrist who said “don’t you know.” Looking back, I have some explaining to do. Even so, I’m not embarrassed.