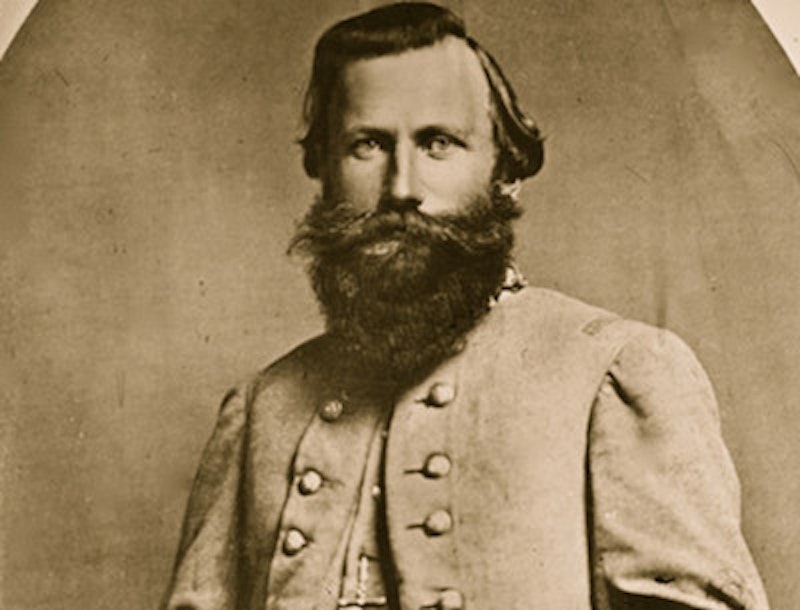

J.E.B. (Jeb) Stuart cut a swashbuckling figure as a Confederate general as he sat astride one of his many fine horses, a long ostrich plume extending from his jaunty slouch hat, his golden spurs glittering on his long boots. A red sash lent his gray uniform just the right dash of color. There might even have been a whiff of cologne about him, or so they say.

The native of Patrick County, Virginia's one of only three Confederate generals (he's joined by Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson) memorialized with a statue on Monument Ave. here in Richmond, but it's not because of any battlefield-chic look he pioneered—his prowess as a cavalryman who refused to settle for just “enough” earned him that distinction. One hundred and fifty-six years ago today, on June 12, 1862, the 29-year-old cavalryman embarked on a feat of military audacity that would breathe new life into the beleaguered South. Eventually it came to be known as the Ride Around McClellan.

Robert E. Lee, who'd just taken command of the Confederate Army, was nervous at the time. George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac, which was then just nine miles from Richmond, had slowly advanced on the city throughout the spring, causing thousands to flee. But Lee found some measure of comfort in his suspicion that the tentative McClellan was vulnerable to a counterattack. Needing verification before he could plan one, Lee ordered his cavalry chief to gather the best of his troops and scout the enemy’s right flank for weakness.

Stuart surprised his commanding officer by boldly suggesting more—he'd take his troops on a lap around the entire enemy army, which was the largest fighting force ever to have been assembled in the Western Hemisphere. Lee understood that Stuart's idea presented an opportunity to demoralize the Federals and get some badly needed good news into the newspapers, but he ordered his flamboyant subordinate not to risk hazarding his command by overreaching. Whether or not he thought that was actually going to happen is debatable, given his familiarity with his cavalryman's tendencies.

The mission was planned in secrecy. At 2 a.m. on the 12th, 1200 of Stuart’s best cavalrymen, including General Lee’s son “Rooney,” began a northward march from Richmond in the general direction of the enemy’s right flank, although the intention was to fake McClellan into believing the troops were en route to joining up with Stonewall Jackson’s troops in the Shenandoah Valley. After several skirmishes with Federal troops, Stuart made it to the village of Old Church. By this time he'd determined that McClellan’s right flank was indeed vulnerable, meaning that he'd arrived at that place where, as General Lee had instructed him, he should be content with his accomplishment “without feeling it necessary to obtain all that might be desired.”

But holding back wasn't Stuart's style. Plus, the enemy had identified his location, meaning he couldn't retrace his tracks back to Richmond—that's what they’d expect him to do. So he decided to make it back to the Confederate capital by riding completely around McClellan's forces. Having successfully reconnoitered one flank, Stuart figured he'd scout another one. Maybe he'd even get a chance to capture his father-in-law, Union cavalry Gen. Philip St. George Cooke, who’d caused a rift in the family by siding with the Union. As Stuart would later put it in his report, this was an opportunity to strike “a boastful and insolent foe, which would make him tremble in his shoes.”

The Federals were slow in responding to the news that the enemy cavalry was behind its own lines, as Stuart knew they’d be. He had the element of surprise working for him, allowing his troops to burn down schooners at Garlick’s Landing and then, at Tunstall Station, hit the enemy's main line of supply, the York River Railroad, ripping up track and tearing down telegraph poles.

Stuart had his hubris tested when reckoning he was close enough to hit the Army of the Potomac's main supply base for its march towards Richmond—White House Landing on the Pamunkey River. Destroying that prize would force McClellan into retreat and make the youthful Confederate general an instant legend, but Stuart was able to resist that gambit. It was time to get back to Richmond.

At Providence Forge, stone abutments were all that remained of a destroyed bridge. Stuart’s men took the wood from a nearby barn to rebuild it, and then set fire to it after they'd made the crossing, just as the Union cavalry was approaching.

On the morning of June 15, Stuart rode ahead of his troops to deliver the payload of intelligence he'd gathered to Robert E. Lee. His men, of whom he'd only lost only one in battle, would arrive in Richmond the next day, with 165 prisoners and 250 mules. The newspapers ate it up. Stuart, described by Stephen Vincent Benét in his epic poem, John Brown's Body, as “Lover of gesture, lover of panache,” had turned the formidable Army of the Potomac into a laughing stock, boosting the South’s lagging confidence.

The Ride Around Richmond provided Lee with all the information he needed to plan his attack at Mechanicsville on June 26, the first of the Seven Days’ battles that doomed McClellan's Peninsula Campaign, aimed at capturing Richmond, to failure.

In May, 1964, Stuart took a bullet at Battle of Yellow Tavern, six miles north of Richmond, after which he died an agonizing death. Stonewall Jackson had died the previous year at the Battle of Chancellorsville in Virginia. Robert E. Lee could only hang on until April, 1965, when he would surrender to Union General Ulysses S. Grant near the village of Appomattox Court House.