Experimental fiction is usually experimental in pretty predictable ways; stream of consciousness, Kafkaesque absurdities, dreamlike sequences, cut and paste. What I love about Aleksandra Lun's The Palimpsests is that, even though experimental fiction is usually experimental in predictable ways, it manages to find a new way of being new. It repeats itself.

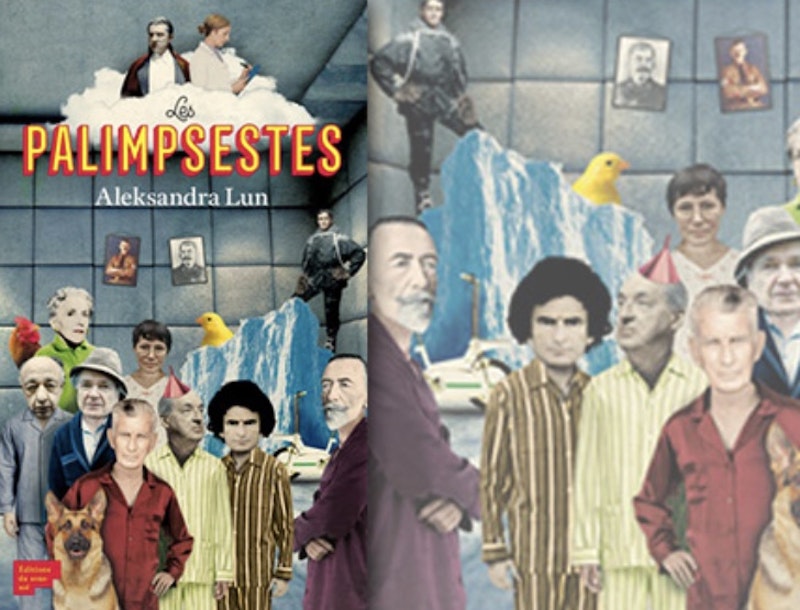

Lun is a Polish author who writes in Spanish; her novel is about Czeslaw Przesnicki, a Polish author who writes in Antarctic. Przesnicki's first hugely unsuccessful novel drew the ire of his Antarctic-speaking peers, who beat him soundly for daring to trespass on their language. He ended up in a Belgium asylum, where he laments the death of his sex life and writes a second novel about a stunt double in the margins of a Dutch newspaper while receiving treatment to help him stop writing in a foreign tongue. Also committed, in typical post-modern style, are Vladimir Nabokov, Joseph Conrad, and other real life polyglots, who dispense wisdom and witticisms while Przesnicki weeps, throws furniture, and is given injections.

The novel, narrated by Przesnicki, is a hoot; it reads more like a series of gags than like a connected narrative. Przesnicki's tragic relationship with Ernest Hemingway, for example, ends when "Ernest upped and shot himself, leaving me nothing but a confusing farewell letter about a lost generation, the restroom of a Parisian bar, the two world wars, the Spanish Civil War, and a young soldier who tried to escape by bicycle."

These punchlines are hemmed round with obsessively repeated descriptions or phrases, which then become punchlines themselves. Whenever Przesnicki mentions his psychiatrist, he also mentions her "impassive eyes" and her endless and ominous note-taking. Whenever he mentionsbeing held in Belgium, he dutifully adds that it’s "a country that has had no government for the past year." He describes his second novel using the same blurb about a stunt double probably 10 times (his interlocutors always tell him it sounds a little too pretentious.) The English translator Elizabeth Bryer in her afterword says that the book's language evokes psychobabble and professionalese; the vocabulary feels constrained and comically obtuse.

The obsessive repetition hem Czeslaw around, like the walls of the asylum. His second language has imprisoned him, and the language of the book imprisons him; he's constantly staggering from those impassive eyes to the country that’s had no government, to his pretentious book description about a stunt double, to "I fell asleep" (the words which end almost every chapter.) It gives the book an uncanny, claustrophobic air of disorientation, as if you’re stuck with Czeslaw in an obsessively repeated description that’s closing in. Language is like a box the author has made to keep you in your place.

The repetition is exhilarating. Books just aren't usually put together like this. Good authors, supposedly, use repetition with sparing caution. You're supposed to keep the prose floating along, like a stream going forward, rather than a stream going forward and then doubling back to put you at the start of the stream. Each ugly clumsy switchback reminds you that your experimental fiction here isn't experimental in a predictable way. The limits of an awkward language that insist on making itself known becomes a kind of liberation.

Przesnicki whines incessantly about forgetting Antarctic; he can't remember verb conjugations; the vocabulary slips from his flabby forebrain. He says, "I fell asleep… I fell asleep… I fell asleep" in part because he doesn't know what else to say. He’s a bad writer. But bad writing is also new and beautiful, which is why the writer using a foreign language is often the one with a new beautiful style of writing. The Palimpsests is experimental in unpredictable ways, like a country that’s had no government for the past year, or someone speaking in a language that isn't quite their own.