During the 1970s Dan Reed was a ubiquitous presence in Miami’s comic scene who worked as an apprentice under C.C. Beck. The young artist had a special place in his heart for Captain Atom, Blue Beetle, The Question, and other characters from Charlton Comics’ 1960s Action Hero titles. In the early-1980’ Reed turned his love for comics into a career by taking a short cut to the pros via Derby, Connecticut.

With Charlton still entrenched in the aftermath of 1970’s financial disasters, he spied a window of opportunity. Reed showed up at Charlton’s Derby offices offering his services free of charge. Impressed by his work, the down-on-its luck comics line (desperately in need of a fresh re-start) then asked the artist to fill an entire book with new content. This became the first 1980s issue of Charlton Bullseye. It helped that veteran fanzine contributor/Warren Publications writer Bill Pearson was then Charlton’s assistant comics editor. Pearson and Reed provided Charlton with a heavy connection to the fanzine world, a fresh talent pool of outsider artists and ambitious amateurs who were all willing to work for free.

When a name for this new series was needed the company decided to revive the old moniker that was used for the semi-pro fanzine Charlton Bullseye. This B&W title ceased publication five years before the color Bullseye comic series began.

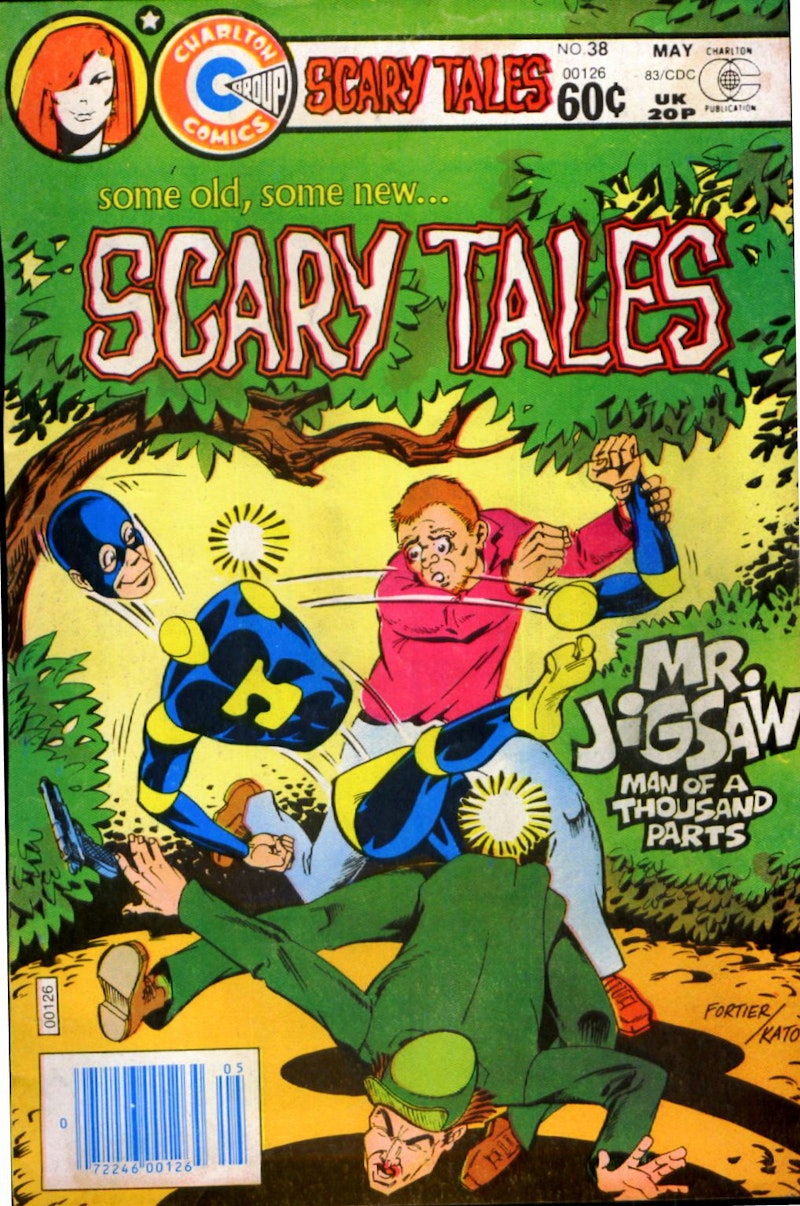

The amateur submissions flooded in. By the time Charlton Bullseye’s 10-issue run ended in late-1982 there were nearly 250 pages worth of material languishing without a home. A chunk of that orphaned content eventually appeared as cover art (for Ghostly Tales, Scary Tales, Beyond The Grave, Attack, War, Billy The Kid, Gunfighters, Ghost Manor, and Haunted). In 1983 several issues of Scary Tales and one issue each of Ghost Manor and Attack showcased new amateur stories and interior art.

Charlton’s new content ran the gamut from imaginative eccentricity to tweaked takes on genre fare. Charlton Bullseye no. 6 had the series’ best superhero content. It starred the outré character Thunderbunny, an anthropomorphic creation from Martin Greim that first appeared in fanzines during the 1970’s. Thunderbunny’s first appearance in Bullseye stretched superhero genre parameters with an incomparable origin story that confronted global war, refugee issues, and identity politics. Bullseye 10 contained two more Thunderbunny stories: an emotional tribute to 1940s comics called “Hero With A Heart Of Gold” and “The Attack Of Big CAM,” an adventure where the musclebound rabbit found himself up against a mad bomber with an irrational hatred of fast food.

Bullseye’s fan mail was just as fascinating as its comic content. Pearson and editor-in-chief George Wildman rarely replied to fans’ opinions. The Bullseye letters page primarily functioned as a fans-only soap box. Excitement developed around the fact that these comics were made by amateurs, including many whose experience level was no greater than that of the fans writing in. A feeling of comradery shines through as do some charming glimpses into fans’ personal lives with letters detailing how they found Bullseye, how their devotion to the book inspired them to travel all over their hometowns searching for the title (Charlton’s in-house distribution system wasn’t the most reliable), and many letters reveal just how young the fans could be (correspondence often concludes with phrases like, “O.k., that’s all for now, my mom is calling me for dinner”).

Charlton Bullseye was sometimes overloaded with exposition, abstract panel designs, and op-art layouts that made every page feel like a dense mini-comic within a comic. This disorienting maximalism resembles what might happen if Jack Kirby tried to draw a futuristic megalopolis right after ingesting magic mushrooms. On the opposite end of the freak art spectrum, there’s the hallucinogenic minimalism of colorist Wendy Fiore. Her luminous opaque backgrounds bring to mind the work of James Turrell, the contemporary installation artist now famous for inspiring the production design of rapper Drake’s “Hotline Bling” music video. Bullseye 5 features a defining example of Fiore’s style in the book-length story “Lair Of The Assassin” by Bradd Meilke & Chas. Truog. The colorist’s pastel glow transformed this barbaric sci-fi yarn into a blurry ambient zone-out.

All of this bore the mark of creators who knew their time in the national spotlight was limited. Other than Thunderbunny, none of the Bullseye characters were featured in more than one issue, though stories and art from Mitch O’Connell, Michael Grace, Dan Reed, and the team of Gary Kato & Ron Fortier appeared in several issues of Bullseye and other Charlton titles. Subtlety was not an option. The amateur creations had to make splash or risk being lost in the sprawl of serialized characters that dominated Reagan-era magazine racks.

Bullseye 3 and 8, and Scary Tales 37 presented modernized takes on the creepy subversive style of Charlton's mid-late 70's horror material. Scary Tales 37 featured Canadian writer/artist David Roman’s “Alien Encounter, a meditative story written from the first “person” perspective of a wild animal. Its nerdy language is steeped in marine biology, elements of Proust, and early sci-fi. Roman’s gentle illustrations provide a gorgeous counterpoint for the heavy narrative. As a cathartic mutation freed from the chains of formalism, “Alien Encounter” exemplifies everything that was great about Charlton Bullseye and all of Charlton’s early-1980s output.