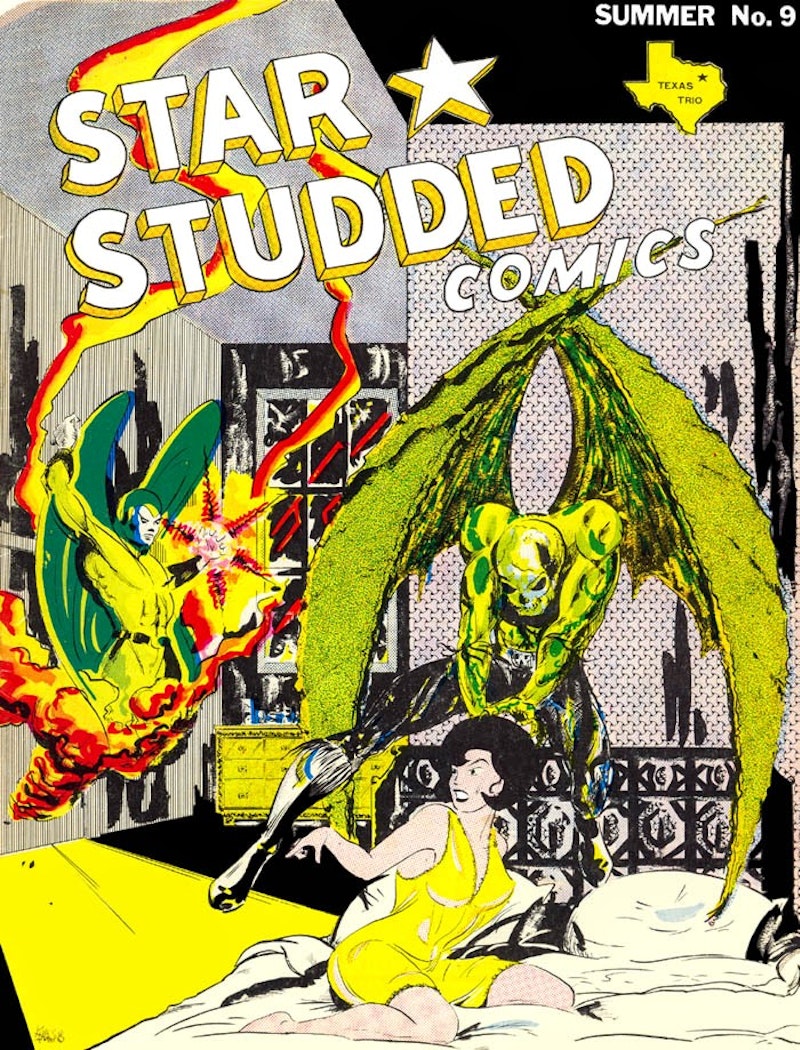

Biljo White, Richard “Grass” Green, and Landon Chesney are just a few of the early zine visionaries who appear in Fandom's Finest Comics. These creators fused the escapist minimalism of Golden Age comics with the DIY aesthetics of modern graphic novels and small press experimental comics. Their rough-hewn fantasies came from a prescient subculture unified by the belief that comic books were important works of art.

When elements of reality slipped into these books they were mostly related to individual artists’ personal lives or fandom-centric inside jokes. Bill Schelly’s annotation doesn’t give much analysis to non-aesthetic influences and that’s for the best. The contextual silence gives readers a chance to come to their own conclusions about what could’ve wrought all of the reckless creativity that makes these works so powerful. This blurriness is also the mark of cultural development—these creators were using their work to carve out a niche. Early zines came from a “safe space” as they were specifically made for and by passionate comics fans, collectors, and aspiring pro-artists. Whether or not casual readers understood their esoteric context wasn’t a big concern.

Being a dedicated comics fan in the 1950s and 60s sometimes brought ridicule, embarrassment, and humiliation, particularly for teens and others who faced confrontations from school bullies and immature phobes. Comics’ ever present secret identity trope had a special appeal to bullied kids from marginalized backgrounds. As a gay man living in the closet for much of his life, Schelly developed his bond with fandom in response to a bigger alienation caused by the intolerance and homophobia that was common in the pre-Stonewall era. His need for an unconditional acceptance of his secret sexuality was just as strong as the need to create comics and zines. When Schelly died suddenly in 2019 The Comics Journal ran a tribute to the late creator/archivist that highlighted the crucial role tolerance played in fan culture’s birth: “In printing his own zines Schelly had become ‘a member of a brotherhood.’ In the 1960’s… Fans were motivated by a desire for inclusion and connection, and when he came out to his fellow fans he found that he was no less welcome in the “brotherhood.’”

In the pre-Comic Con dark ages it was a miracle for amateurs to receive any support. Without an art degree, graphic design experience, and well-established connections to major publishers, getting a foothold in the pre-Reagan era comic book industry was tough. For those amateurs who got beyond the zine scene the move to the pro-level required patience and humility. Morale boosts from the zine community were also ingredients for success.

Acerbic genius Alan Hanley’s “Good Guy! Champion Of Clean Living!” (originally from COMIC BOOK no. 5) appears in Fandom’s Finest vol. 1. Hanley’s career began in the early-1960s. The writer/artist would die before seeing his work professionally published. His satirical piece “The Mitey Buggers” ran in Charlton Bullseye no. 6 about a year after he lost his life in a car accident and nearly 20 years after he began self-publishing zines (an interesting coincidence: Hanley’s fellow zine pioneers Martin Greim and Jerry Ordway also had early pro-work published in Bullseye 6). The artists Jim Starlin, Jeffrey Catherine Jones, Dave Cockrum, and Alan Weiss all toiled in obscurity for years while honing their chops in DIY zines.

The best story from the first volume of Fandom’s Finest is George Metzger’s “Master Tyme and Mobius Tripp” (originally published in Bill Spicer’s Fantasy Illustrated). Metzger would become legendary for creating ultra-detailed imagery in Moondog, The East Village Other’s Gothic Blimp Works supplement, and other hippie underground titles. While there’s intricacy galore, the representational element that also dominated Metzger’s better-known works forms no part of “Master Tripp…” The ambitious story’s op-art influenced scrawling and its main creature share many traits with the untamed nature of early fanzines. They were shambolic, passionate, and consumed by relentless imaginary forces.