I’m a bit tardy to the media’s marking of Woodstock’s 50th anniversary, just as I was tardy to Max Yasgur’s 600-ace parcel of land in upstate New York (Bethel) in 1969. In fact, I was so tardy, I didn’t go. I wanted to, but at 14 my normally permissive parents put the kibosh on the idea instantaneously, and shared belly-laughs at my audacity for even bringing it up; and this was a month prior to the three-day concert, before the highway jams, rainstorms, mud and the “groovy” coining of “Woodstock Nation.” My 18-year-old brother didn’t need permission from our parents to attend, but his boss at the local hardware story in Huntington, New York wouldn’t give him the weekend off.

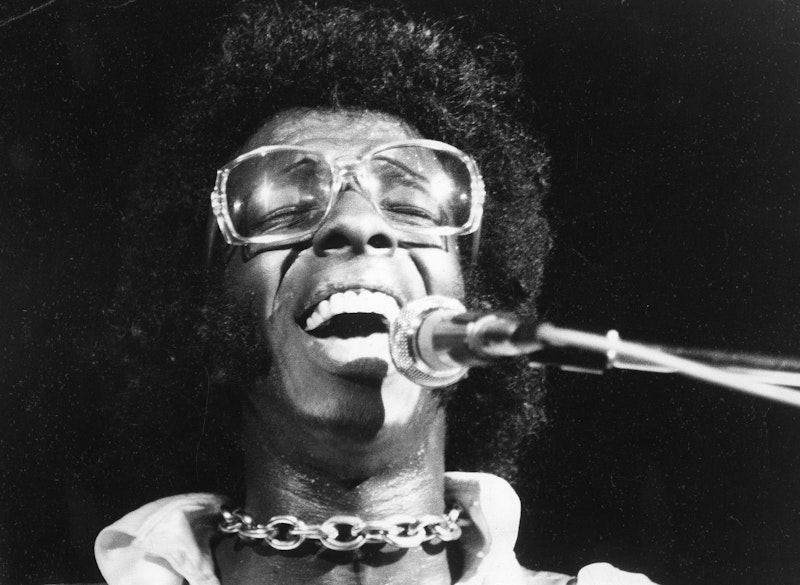

I sure wish I’d gone, despite the uncomfortable accommodations, “brown acid” (I just began, as politicians used to say, “experimenting” with pot at the time, which was a big enough step) and loads of nude bathing that probably would’ve made me blush (or not!). None of my friends attended, although later, I encountered a number of people, at college and work, who did, and they had varying memories, but none regretted the experience. Really, the chance to see The Who, Hendrix, Crosby, Stills & Nash, The Incredible String Band, Richie Havens, Sly and the Family Stone, Joe Cocker, Jefferson Airplane, Country Joe, Arlo Guthrie, Santana and The Grateful Dead on the same weekend is still staggering. I’m certain it was by and large very cool.

Last week I read a sour roundup of contemporary reports about Woodstock—and a retrospective slam of the event—by conservative journalist Steven Hayward, who’s 60 and says he “sadly belongs” to the “appalling baby boomer generation.” (The non-stop apologies for the generation of your birth is remarkably narcissistic; no one has a choice when they enter the world. And I suspect that’s a pro forma “apology” from Hayward, who’s fashioned a very successful career.) I’d suppose young Hayward was an “Up With People” fan, and if he listened to music, it was probably on the order of the Osmonds and Robert Goulet. Or maybe he was a snobby guy, who dug Cisco Huston, Leadbelly, Coltrane and Mississippi Fred McDowell and fretted about “cultural appropriation.” Joshing!

This is how clueless, or maybe just antagonistic Hayward—still!—is to a “counterculture” that’s long been consigned to photo albums, diaries and books.

He writes: “In fact the purported innocence and new moral world of Woodstock would prove as evanescent as the summer shower that cooled off the concertgoers at Max Yasgur’s farm. A few months later the attempted sequel to Woodstock at California’s Altamont Pass ended violently when the Hells Angels hired as security proved they were not yet ready to be part of the Age of Aquarius. The Hells Angels beat a concertgoer to death just a few feet in front of Mick Jagger, who was in the middle of singing ‘Sympathy for the Devil.’ In contrast to the encomiums to Woodstock, there was little media commentary suggesting that Altamont showed a dark side of the counterculture.”

Ahem. One, Altamont was a last-minute idea cooked up by the Stones after a long tour promoting their new record Let It Bleed, a free show with a number of available bands (Airplane, Flying Burrito Brothers, Santana, Ike & Tina Turner) that hurried to the scene. Maybe September’s Isle of Wight festival, which featured Bob Dylan, acted as a UK follow-up, but not Altamont.

Second, as is commonly known, Meredith Hunter was killed during the Stones’ “Under My Thumb” and Jagger had no immediate idea it happened. Invoking “Sympathy for the Devil” makes for better copy for Hayward, but if he’d seen the Maysles Brother’s Gimme Shelter, out just a year after Altamont, he’d have known that. And the Altamont fiasco was widely-reported—to the glee of some mainstream publications—and a few weeks later in an exhaustive, and excellent, series of stories in Rolling Stone. In addition, I knew about Altamont in the next couple of days (depending on leadtime for publications), from newspapers and WNEW-FM in New York City. Perhaps young Hayward had his nose buried in National Review at the time.

You can’t ignore the mythology surrounding both Woodstock and Altamont—four months apart—as the zenith and nadir of the “hippie culture,” but that’s really just lazy shorthand. In between the two concerts, there was the October 15 anti-war Moratorium, which attracted 250,000 demonstrators to Washington, DC—and twice that number a month later—as well as sit-ins, teach-ins and the like at schools and centers all over the country. It reached the junior high level; on that day, Tom Demske and I, 9th graders, led an anti-war assembly (wearing the black armbands for the occasion) that was, incredibly, sanctioned by the school’s principal.

Historians, and those alive at the time, differ on when “the 1960s ended,” and it’s really arbitrary. The most common demarcation of the decade dates from the assassination of JFK to Nixon’s resignation, and that makes sense. My own view is the “good vibes” ended on May 4, 1970 at Kent State when the National Guard killed four students—and protests became less well-attended—and probably more significantly when Nixon strategically ended the draft.

Hippie culture splintered into “back to the land” communes, a thankfully brief Jesus Movement (Godspell, “Spirit in the Sky,” “Jesus is Just Alright"; in 11th grade, one of my buddies, momentarily riding the wave, told me, “Hey man, fucking is better with Jesus in your heart.”), and then the mainstream acceptance in the early-70s of “hippie” behavior—long hair, widespread drug use, jeans and flannel shirt uniforms—by latecomers who’d made fun of the “movement" just a few years earlier.