I wrote a book about the Erie Canal, filled with pictures of old ruins, but what struck me was the forward-looking ethos of early-19th-century America. This country’s engineering profession began with the upstate New York canal’s building, with onetime surveyors learning on the job how to carve through rock, drain swamps, make hydraulic cement, and use wheeled devices to pull out tree stumps. The canal made it far easier for Americans to move, to new careers as well as new towns. New ideas moved along the canal route, too, including Mormonism, spiritualism, utopian communities and women’s suffrage.

By the early-1820s, London investors were eager to buy Erie Canal bonds, even though it was just a decade earlier that British troops had burned Washington D.C. The canal’s foremost advocate, New York Gov. DeWitt Clinton, opened the waterway with a weeklong celebration in October 1825, topped by pouring Lake Erie water into the Atlantic. The U.S. had come to be seen as a country that embraced the future, a reputation that would persist over centuries.

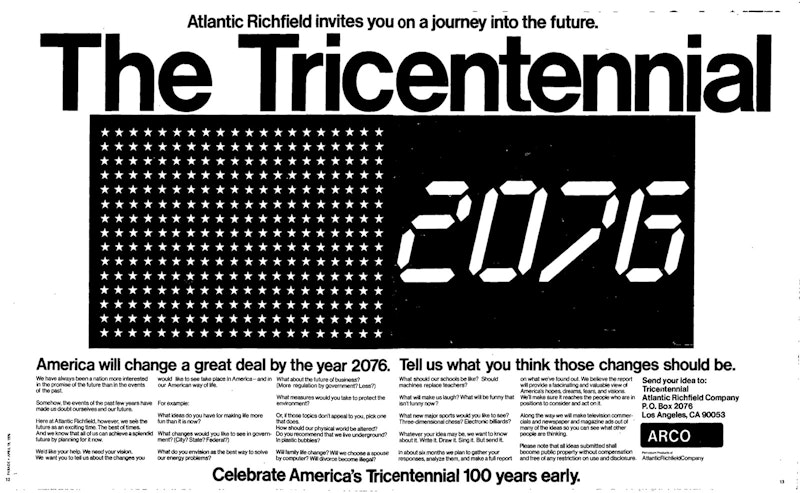

The current decade will see the canal’s 2025 bicentennial, followed the next year by the U.S. Semiquincentennial, officially marking the nation’s 250th anniversary. Recalling the U.S. Bicentennial, I know such celebrations can’t conceal a nation’s troubles, as in that post-Vietnam, post-Watergate, inflation- and crime-ridden juncture of national self-doubt. Yet the 1970s of my childhood still had some vivid and hopeful views of the future, as with NASA’s sketches of orbital colonies or kids’ letters to the people of 2076.

In his book Evil Geniuses, Kurt Andersen complains that American culture has become increasingly past-oriented over the last several decades. Looking through old photos, he notes that the look of everyday life—clothing, vehicles, buildings—used to change much faster, say in 1950–1970 compared to 2000–2020. He sees a political aspect to this: “The general default to nostalgia that started in the 1970s helped soften the ground for the right’s project,” making people more amenable to old-style economic nostrums and a lack of political reform.

I think there’s something to that. But I don’t think it’s a condition that holds indefinitely. Granted, I overshot with my pre-election prediction that a 40-year span of right-wing dominance was as good as over. But the election results suggest fatalism is not in order. Old voting patterns have broken up. Arizona and Georgia now look to be swing states, and no one can be sure what’ll happen in the latter’s runoff elections in January.

Some of my fellow Biden supporters reacted to the gradually unveiled election results with grimness, even as it became apparent that Biden was heading to victory. They lamented that the Senate hadn’t flipped, the presidential race had been closer than they expected, so many millions had voted for Trump and thus shown they’re fine with racism, authoritarianism, etc.

True. But there’ve always been millions ready to vote for ill-conceived alternatives. The remedy is to show that when your candidates and ideas gain, better things happen. That will require some forward-looking visions of America, not despair that the country is so benighted.

Here’s something I’d like to see: more wildlife corridors. Animals have better survival chances when they’re able to move from one area to another, rather than confined to a single protected zone; that involves such measures as building overpasses and underpasses to circumvent highways. The idea has made headway in policy and legislative circles, for example in a bill that passed the House last summer with some Republican support. The Democrats’ 2020 platform contains a proposal known as “30 by 30,” to protect 30 percent of U.S. land and waters by 2030, which includes a focus on corridor conservation to safeguard migratory routes.

The Erie Canal, connecting the Eastern Seaboard to the Great Lakes, played an important role in holding the developing United States together in the 19th century, keeping East connected to West even as North and South frayed. Nationwide networks of parkland and wilderness areas might be a key to keeping a culturally divided U.S. together in the tumultuous 21st century.

—Kenneth Silber is author of In DeWitt’s Footsteps: Seeing History on the Erie Canal and is on Twitter: @kennethsilber