Burt Bacharach raised slumming to an art form. A sophisticated composer fascinated by the intricacies of jazz and the possibilities of tonal colors in small ensembles, he spent his career writing ephemeral pop hits for the most mainstream of mainstream performers—Tom Jones, Gene Pitney, Herb Alpert. Rhino’s massive three-CD, 75-song compilation, released in 1998, is hour after hour of dramatic strings surrounding soaring paeons to love and heartbreak, endlessly sinking into a milky sea of melodrama glop.

The glop, though, keeps winking at you, with a world-weary suave. The perfect façade of Bacharach’s innocent songs are always peeling away to reveal cynicism and/or concupiscence. He’s the aural equivalent of Billy Wilder’s brightly earthy sex comedies, sun-dappled, horny, and knowing. The 1963 Gene Pitney hit “Twenty-Four Hours From Tulsa” see-saws back and forth between triumphant Latin-tinged surge with horn flourishes and melancholy ballad throb, as Hal David’s lyrics tell the sad (?) story of a traveling man who abandons his wife on the spur of the moment for a woman he meets in a hotel. “I can never, never, never” he moans, as the music hits a false cadence. The narrator is trying to trick himself into believing he’s really tormented, before the big finish with back up chorus declares, “go home again” like liberation.

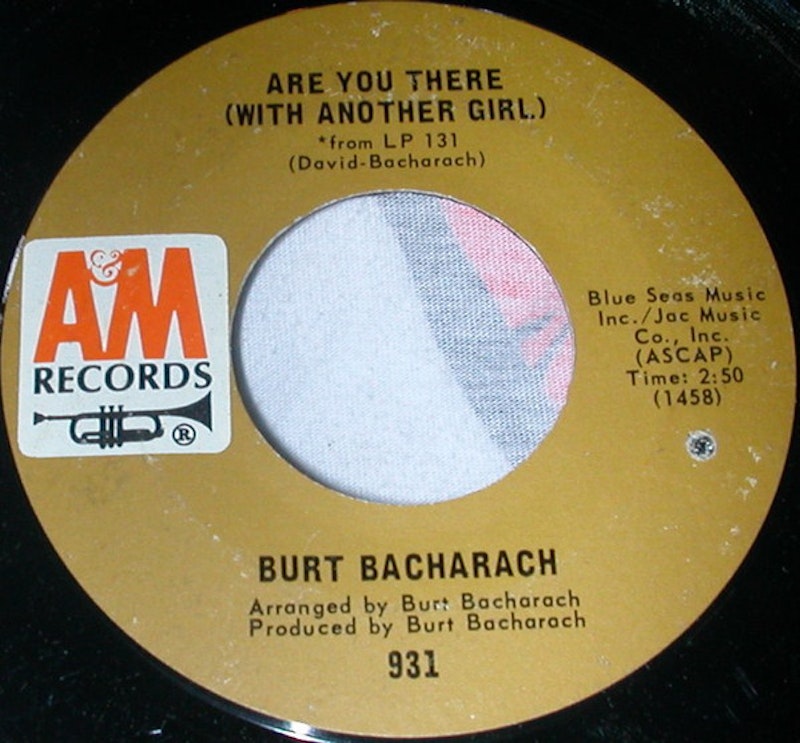

And then there’s the marvelous David/Bacharach “Are You There (With Another Girl)." Sung by Bacharach’s greatest collaborator, Dionne Warwick, the narrator in the song stands outside her boyfriend’s house and sees one too many silhouettes on the window shade. The vocal line rises up in an exulting spiral, “Love requires faith, I’ve got a lot of faith…but!” The last syllable hits like an offhand backhand, before Warwick drops to the bottom of her register again, innocence trying to wrestle cynicism back down from where it’s peeking in that window.

It’s impossible to list all the highlights: Gene McDaniels’ “Tower of Strength,” with his growling sobbing vocal about how he’s nothing of the kind, as the honking trombone mocks him; Tom Jones heavy-breathing hiccupping go-go grind encouraging men to lie to their sweethearts with starry-eyed calculating glockenspiel glissando; the late-period 1981 Christopher Cross “Arthur’s Theme,” with the smooth jazz sax solo wistfully swaggering between the moon and New York City; Manfred Mann checking off syllables like he’s flipping through names in his little red book; Dusty Springfield sighing as she gives that bossa nova beat the look of love; Jerry Butler soulfully commiserating with the dissonant piano as it prepares to break up with him; Karen Carpenter still wanting to be close to you after one false endings, and even after a second.

Not everything is great, but even the disappointments—like Herb Alpert’s too fruity “Casino Royale” or Bobby Goldsboro’s racist “Me Japanese Boy I Love You”—don’t seem out of place in a collection so attuned to the sweetness of disappointments and the disappointments of sweetness. “Weeks turn into years/how quick they pass/and all the stars/that never were/are parking cars and pumping gas,” Dionne Warwick sings with a sensuous clarity and swing over a stop-time organ-vamp. Bacharach and his collaborators make failure sound like sex and give joy the sting of failure.

Bacharach managed to keep making hits for four decades, but the 21st-century emphasis on rhythm over melody and explicit over implicit sex isn’t congenial to his aesthetic. He’s over 90 now, and while his songs still show up on movie soundtracks, his relevance has diminished rapidly even since the release of this compilation. But that’s okay. As Bacharach knew, nothing lingers like the knowledge that even the purest love will eventually get up, sigh, and to the sound of swirling strings, walk on by.