During the late-20th century reactionary music writers and fans worshipped grunge guitar rock. Everything from punk to indie rock, to chart-topping alternative sounds were treated as musical forms of salvation that brought listeners and artists closer to an idealized “organic” expression. NME writers Paul Morley, Ian Penman, and their progressive ilk were at odds with the “rockists” championing (what Morley called) the “overground brightness” of Duran Duran, the New Romantics, synth pop stars, electronic musicians, and others driven by the imperative to make pop for pop’s sake. Both niches were comprised of lapsed zealots who embraced punk’s rebellious hype. When they later slagged punk’s performative revolution as a failure, these jaded scenesters began supporting the wide swathe of late-1970s-to-90s artists who were branded “post-punk.”

A milieu born of a similar cultural “boom and bust” existed during the late-1960s. Greg & Suzy Shaw, Miriam Linna & Billy Miller, Tim Warren, and others have all done exhaustive archival work to prove that punk rock music originated before the 1970s. Despite their efforts, a nuanced view of Vietnam-era punk’s impact remains elusive, especially when considering avant-garde music artists of the 60s and how they processed garage punk’s effect on the pop landscape. The Sex Pistols, Ramones, and Clash spawned Human League, The Minutemen, and PiL. Link Wray, The Kingsmen, The Troggs, and other early punk stars also inspired a musical reaction, a post-punk expression that served the same purpose as its latter counterpart(s) despite predating the punk cultural milieu’s birth.

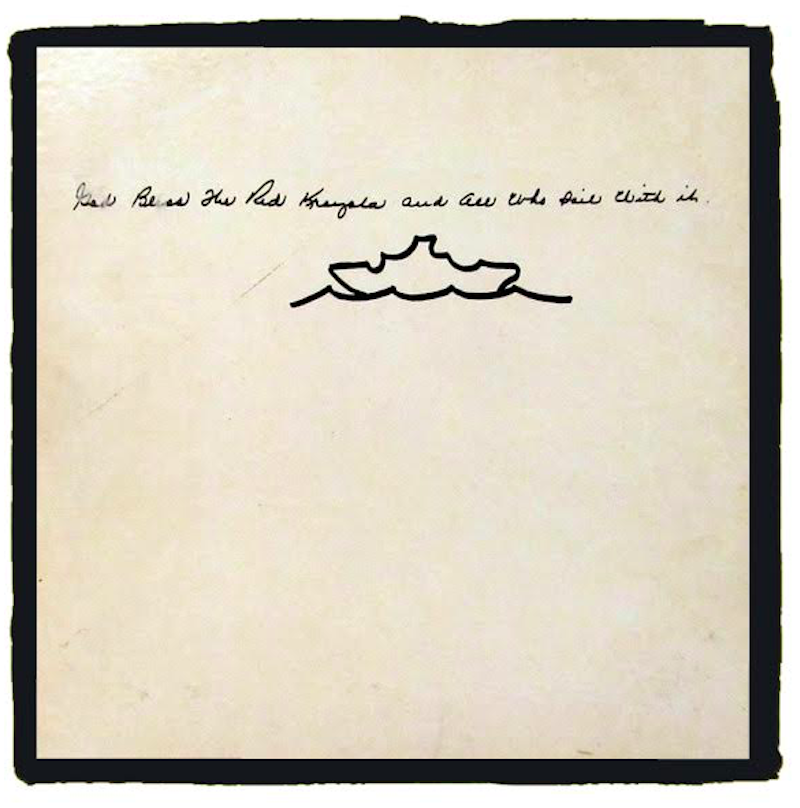

God Bless The Red Krayola and All Who Sail With It by The Red Krayola is the major work of 1960s post-punk. With child-like front cover art, ever shifting/schizophrenic moods, angular arrangements, free jazz improv, and playful Dadaistic lyrics, the 1968 sophomore LP from The Red Krayola singlehandedly created the blueprint for all contemporary post-punk aesthetics. Touches of The Red Krayola’s work can be found everywhere from global DIY cassette culture to the jagged/funky rants of The Minutemen, Gang Of Four, and Elastica, to today’s contemporary noise music. There’s no doubt that they were prescient, but The Red Krayola also represents a distinct reaction to 1960s pop. Elements of 60s garage punk and bubblegum in particular played a big role as subliminal influences on the Krayola approach.

The Red Krayola didn’t seek to simply subvert the mainstream, but to create and inspire a righteous new purpose for music, one informed by leftist politics and the manic media overload immortalized and dissected within the works of McLuhan and Innis(an overload exemplified by the sensationalistic coverage of the 1960s British Invasion, the prime inspiration for most 60s punk bands). Burroughs-like nonsense lyrics splatter across guitar riffs that careen from Kinks-ish savagery to jangly folk-psych sweetness. Atonal noise and awkward silences interrupt anything a pop fan might call music. A collective of lead singers creates the record’s most mercurial element. Sometimes Krayola founder Mayo Thomspon’s understated tenor takes the lead; on other tracks random supporters and friends of the band contribute ecstatic caricatures of melody; one song features a spoken-word piece by a toddler with a barely existent vocabulary.

This music wasn’t easy to dance to. Lovelorn teen Boomers would never hear a Red Krayola track blasting through the p.a. during the local roller rink’s request and dedication hour. By stretching their arms around the widest array of influences possible the band’s recordings were a reflection of the chaotic world they came from, not just the onecultural niche (aka the youth market) predominantly embraced by their shaggy-haired contemporaries. Krayola’s dissonance, twisted melody, and indecipherable weirdness came from a symbiosis of noise and music, an outrageous performance art piece stumbling into an underground 1960s rock concert.

The rock scene in their home state of Texas was dominated by 60s punk, most notably the frantic acid-punk of underground ballroom favorites The 13th Floor Elevators (whose singer—Roky Erickson—plays on RK’s first LP, the improvisational psych classic Parable Of Arable Land). The Elevators and Red Krayola shared a common social circle and were signed to the same record label, International Artists. While Roky and co. balanced their noisy weirdness with sweet melodies and dreamy lyrics, Red Krayola made a conscious effort to be as imbalanced and topsy-turvy as they could. In addition to symbolizing a high tech communications breakdown, God Bless…was a twisted fun house reflection of The Elevators’ crazed riff-age and the dance music culture that surrounded it.