A young woman is unsettled. She paces around an apartment, while a man looks on, confused in an attempt to reach out to her. The window curtains are pulled tight. This couple is separated from the external world, and the unbearable artificial lights paradoxically conceal their intents. They’re unable to express their feelings for each other adequately but it’s really the woman who’s uncertain about their relationship. She’s made a decision to leave the man, despite not knowing why or what she wants out of life.

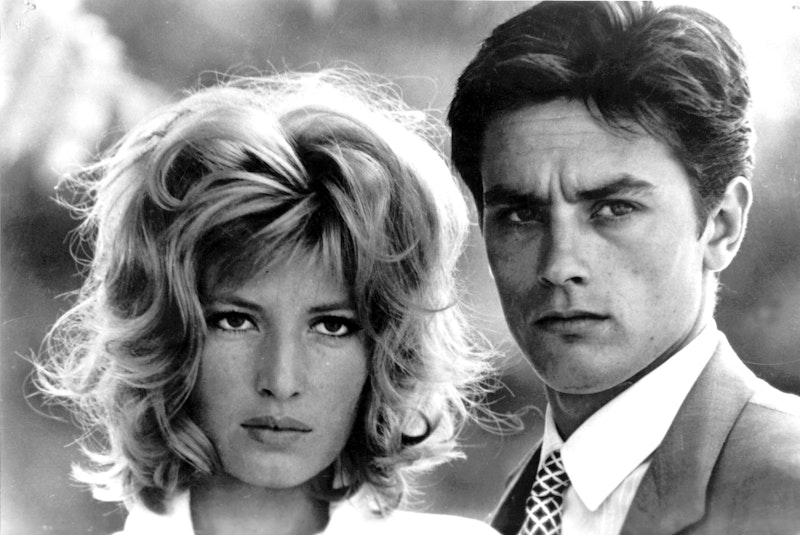

This is the opening of Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’eclisse (1962) that follows the story of Vittoria (Monica Vitti) and Piero (Alain Delon) as they navigate through the streets and spaces of Rome in order to establish their relationship. Piero works as a stockbroker and Vittoria as a translator. Their lives are unconnected except for the fact that Vittoria’s mother plays the market in an obsessive effort to escape poverty, and sees Piero daily at the stock exchange.

Vittoria sees this obsession as an unhealthy habit but she also has some understanding for her mother who’s been a widow ever since Vittoria was a small child. Things begin to fall apart when Vittoria’s mother (along with many others) loses a lot of money on the stock exchange. As much as Vittoria cares for her well-being, she lives a separate life. In fact, she’s not only disconnected from her mother but from the rest of the world.

Piero represents a break in the anhedonia and acedia that Vittoria feels. He pursues her, yet even he’s not sure why. He does have more passion and playfulness, and he tries to bring that out in Vittoria as well. At first, she resists him, and plays a game of submission and withdrawal. Antonioni brilliantly teases out the essence of a relationship between a man and a woman. The masculine pursuit, showing off with material goods, and the need for sex but also closeness. Vittoria embodies the feminine withdrawal but there’s something more in her, which goes beyond the dichotomy between the feminine and masculine. Her alienation is genderless, and is simply human.

Antonioni sees great significance in cityscapes. Vittoria’s and Piero’s jobs are incidental. What’s more important is the spaces they inhabit, and the objects they come in contact with. While Piero is living in “old town” Rome, surrounded by ancient ruins, Vittoria lives on the outskirts of Rome, in a modernist apartment building surrounded by other cold and distant modernist buildings. It’s an endless and undefined landscape of pavement, minimalist street lights, and parking lots. The roads may be winding and some trees occasionally emerge in the frame, but such natural matter is out of place. The people are separated from the passionate bustle of Rome and the imposing ruins, and they too somehow don’t belong in this landscape that resembles another distant, lifeless planet. The streets are almost always empty with a few people walking as if a nuclear bomb went off.

The contrast doesn’t stop with the cityscape. Vittoria visits Piero’s house, which is warm and whose objects include beautiful paintings from Baroque and Romantic periods. The lines aren’t cold but they represent undulating human desires. Despite living there, Piero is also disconnected from the house he inhabits. It’s a space he grew up in but remains indifferent to it. He tries to get close to Vittoria but she places an open window glass between their faces. Their lips touch the glass as they try to kiss. She continuously tries to escape but not because she feels unsafe with Piero. In fact, he’s respectful of her dignity, but thanks to Delon’s presence, he retains masculine aggressiveness because he senses that Vittoria desires it.

She wants to escape him but can’t help but embrace the playfulness of a genuinely erotic game. They desire each other but aren’t sure why. Perhaps, as Vittoria says, there should be no “understanding” between people who are in love. They shouldn’t know why they love each other because then, the supreme mystery of erotic relation between a man and a woman would be lost.

This is what makes Antonioni’s vision excruciatingly and achingly beautiful. Like a painter, Antonioni shows the juxtaposition between eros and alienation, yet the film itself isn’t one of despair. It’s easy to elevate apathy and despair cinematically but Antonioni lets the spaces and objects lead us into the interior lives of Piero and Vittoria. They, but especially Vittoria, are impenetrable but not repulsive.

The body movements that Delon and Vitti exhibit in the film is one of the best and beautiful expressions of erotic love on screen. The passionate embraces are restrained but not lifeless. The movements are choreographed but they’re not mechanical. Rather, the sexual passion between Vittoria and Piero is in itself a piece of Art. Just as we feel they’ll finally belong to each other, they pull away. But there are thousands of unspoken feelings and desires in one kiss, one embrace, one fistful tug at a dress. There are walls and partitions, both literal and figurative, that separate us from each other and from the space. The relationship between Vittoria and Piero is uneven but that’s the nature of an erotic relation between a man and a woman. They become one in a small glimpse of desire until they pull back again, obscured by the existential eclipse, and remain metaphysically separated. And yet, they will see each other “tomorrow… and tonight… and the day after… and the day after that.”