In January 2013, Laura Poitras had finished two-thirds of her “9/11 Trilogy” of documentaries. Both My Country, My Country (2006) and The Oath (2010) received acclaim, with the first examining how U.S. occupation affected the lives of Iraqis, and the second examining adults in other countries and how they were affected by US intervention. In her third film, Poitras wanted to focus on how the political climate affected American citizens.

Poitras was one of three journalists who flew to Hong Kong and received leaked information from Edward Snowden, then a contractor for Booz Allen Hamilton for the NSA. The result, Citizenfour, is not only an unravelling of international surveillance programs, but also a front-row seat to an international incident that’s a piece of history. Citizenfour won both the Academy Award and BAFTA for Best Documentary Feature.

Trilogy complete, Poitras decided to further explore leaked government information with Risk. Without knowing the truth, it’d be easy to assume that Citizenfour (2014) and Risk (2016) were directed by two different people. Risk deviates from Poitras’ trademark of staying behind the camera. Poitras made two films about the same topic, and she began to go about both of them in the same way, but the complications of reality made that impossible.

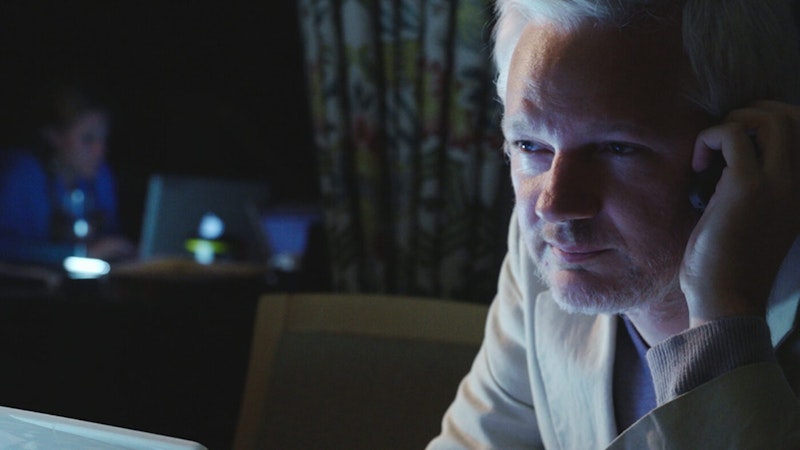

Risk, originally entitled Asylum, focuses on Wikileaks founder Julian Assange. At first, Poitras stays behind the camera and observes, but it becomes clear that this is a completely different world than Snowden was in. When we first see Assange, he’s on the phone with then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s aide, encouraging them to step up cybersecurity practices as Wikileaks believes a large leak of information is imminent. Assange gets into a tense back-and-forth with the staffer, which ends with Assange sneering into the camera and telling the staffer it’s “Your problem, not ours.” Minutes later, Assange freely rants about the safety of other leakers, and then his own, while pouring drinks for himself.

By contrast, Snowden is a Boy Scout. The government contractor-turned-fugitive was 31 at the time of filming Citizenfour but appears more mature than Assange does at age 42. Snowden, the product of a Coast Guard family, sits calmly on a bed with his dog tags around his neck. Snowden had originally sought to serve his country in the Army, but broke both of his legs in training. He takes time to answer questions from the two other journalists in the room, while Poitras stays silent behind the camera. When the hotel in Hong Kong begins to coincidentally perform testing on their fire alarm system, Snowden’s visibly shaken, but overall maintains his composure. On the other hand, Assange is at one point convinced he’s being followed, and casually directs Poitras, as if she were his assistant, to go check it out. She finds nobody.

Poitras sees her usual form won’t work with her eccentric subject and switches it up. Early on, she handles Assange’s sexual assault allegations tenderly, and then puts it center stage. She inserts herself increasingly in the documentary, and openly discusses her disillusionment with Assange. The endeavor is quickly worthwhile as only a few minutes later Poitras pushes Assange on the topic of the investigations, only for Assange to abruptly claim there’s a global “lesbian feminist” conspiracy against him. Furthermore, Poitras informs the viewer via narration a friend of hers was romantically involved with a member of WikiLeaks, who became verbally abusive and slanderous after they parted.

Poitras explores the harsh reality of the group’s questionable ethics and attitudes towards women, as well as the undeniable risk they’re all taking in their profession. Poitras puts herself into the element of risk, as she reveals she’s sure she’s being followed, and her phones tapped.

In an effort to empathize with Assange, Poitras delves into his difficult childhood. Assange’s father was never present, and Assange considers his stepfather his “real father” and took his surname from him. The family’s home burned down, and Assange’s mother and stepfather separated. Soon after, his mother became involved with members of the Australian Cult “The Family.” Clearly a damaged person, by 1996 Assange (25) had been married, become a father, divorced, arrested for computer hacking, and released on a good behavior bond.

Poitras doesn’t shy away from Assange’s bravery and persistence, but doesn’t ignore his misogyny, erratic behavior, and narcissism. In Citizenfour the urgency of the situation makes a character study of Edward Snowden impractical. In Risk it’s unavoidable. Snowden’s motivations are clear-cut, Assange’s are not. Poitras used Citizenfour to complete a trilogy. If viewed as a spiritual successor to Citizenfour, Risk shows the duality of the world of document and information leakers.