Sometimes it feels like Gaspar Noe builds his films out from gimmicks: un-simulated sex in Love, the rape scene in Irreversible, and the “fucking insane” DMT visions of Enter the Void. He works with primary colors alone, and when I heard he was making a movie about dementia, I got scared. Michael Haneke’s Amour wasn’t nearly as crushing as I thought it’d be, a great film nonetheless, but Noe would be cruel and unsparing. Vortex stars European film legends Francoise Lebrun (The Mother and the Whore) and living legend Dario Argento. I don’t know why anyone is surprised that Argento’s performance here, as the husband with a bad heart and a sick, demented wife, is so good—this is the director of Tenebrae, Phenomena, The Cat o’ Nine Tails, and Suspiria. Ditto for Lebrun, who glides into confusion and twilight chaos with more serenity than anxiety.

Argento is preparing a new film book called Psyche, but Lebrun flushes all his work down the toilet while he showers, saying, “I tidied your desk up for you.” Argento is beyond incredulous, and vibrating with rage and suddenly vulnerable: he stumbles out of the shower, mumble-screaming about this “total disaster” as he appears to sink into the same degeneration that his wife is already drowning in. Vortex begins with a brief scene of the couple happy on a nice morning in Paris; after waking up and preparing for the day, they sit outside and look at the sky. “Isn’t life a dream?” And then Noe’s camera goes up into the sky and rotates until it’s completely upside down.

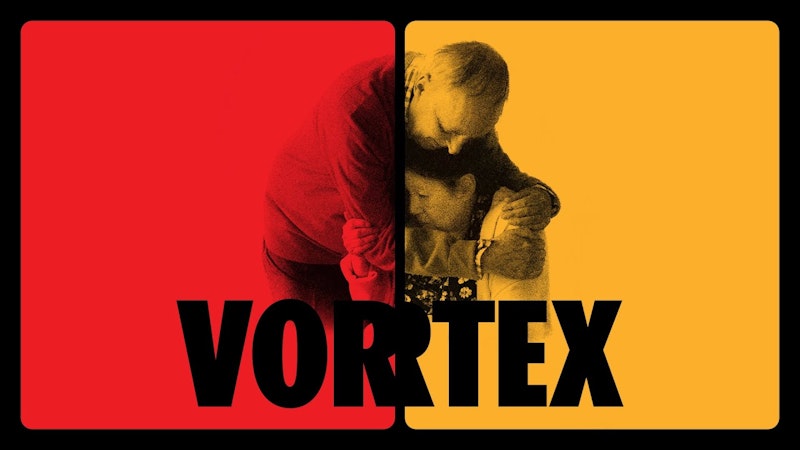

Cut to a widescreen image of the couple in bed: the black line of a split screen begins to sink between the two, and Lebrun is aware of it, or something, happening. Maybe this is when her wires cross and others snap, when she loses the ability to recognize her husband, her son (Alex Lutz), or her grandson. Noe runs all of the credits for the film up front, so that he can end the film abruptly and get the lights back on while the audience is still paralyzed. When he finally reaches the title of the film and the main players—himself and the actors—he displays their names and year of birth. Vortex is dedicated, “To all those whose brains will decompose before their hearts.”

The screen is split for the rest of the movie, with two cameras filming the same events simultaneously, sometimes right next to each other, other times far apart, like when Argento has the heart attack that kills him a few days later. Lebrun doesn’t notice until the next morning, and after so much stress about moving the increasingly sick Lebrun to a facility (she continues to turn the gas on), Argento ironically dies first, and when he does, his side of the screen disappears. It comes back for their son at points, but otherwise, he’s gone, and she can’t remember: she keeps forgetting, amongst all of their stuff, that her husband’s dead. Her neighbors have to remind her. After a few weeks of this, she turns and leaves the gas on for the last time.

Vortex is being sold as another Noe provocation, but for once, his reputation is getting in the way of a harrowing and unflinchingly real look at getting old and dying together. Just as Clint Eastwood demonstrated grace and strength at 91 in Cry Macho, and as the younger Donald Sutherland, Jim Broadbent, and Diane Keaton are willing to star in movies about the elderly that have no respect for them, and are clearly written by people decades younger with contempt for age. No other art form is as suited to the treatment and exploration of death and aging as cinema, for obvious reasons; if certain people are so desperate for a “serious American cinema” to return, why don’t they stop begging for more erotic thrillers and instead insist upon serious dramas with older actors?

One reason may be that getting old isn’t a universal experience. Unlike dying, not everyone will know what it’s like to wander around your apartment alone at 80 looking for your lost loved one. Not everyone will get confused, incontinent or reach the point where they need to take 12 pills a day, none of them fun. Their son’s wicked drug addiction was quelled, but for how long now? After struggling and failing to get his parents into an assisted living facility, he relapses and smokes heroin at home—his young son sees him, but says nothing. This is never followed up on, and by the end, when the ashes of Argento and Lebrun are put into memorial boxes, his son asks him if grandma and grandpa have found a new home.

“No,” he says, “a home is for the living.” Noe cuts back to the couple’s house, first free of them, then free of their possessions, and the camera once again flies up and rotates into the sky, another couple of dreams finished forever.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith