There is the Canon. The films the precocious youngster cites as her favorite—Casablanca, Gone With The Wind—years before she will grasp the meaning of the word compromise. Neurotics who long for an Annie Hall of their own, a cipher to love in spite of her mind-numbing frustration. The 1980s devotees, the bad boys, the Cassavetes, Bergman afflicted: “Give me something Real, and Raw! What life, what marriage is truly like!”

For all its drawbacks—specifically Hollywood’s formulaic and disastrous output—the new millennium has brought independent audiences a genre all its own. A depiction of love that exists beyond the standard star-crossed, forbidden fruit saga. No longer must lauded indies subscribe to the heterosexual model of romance: they are increasingly free to explore alternate forms of that ubiquitous four-letter word, whether it’s platonic or “taboo.”

Below is a wade into three of the year’s most successful variations on this thoroughly modern film. (Currently in theaters.)

Laurence Anyways

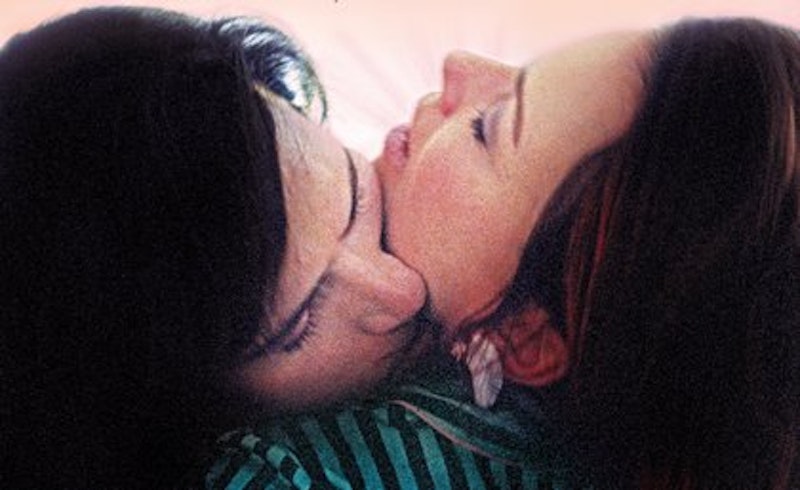

Despite its heavily drawn ’89-‘99 backdrop, it’s hard to imagine a film like Laurence Anyways existing in any time but the present. It chronicles a love affair that is at once undone by Transgenderism, and made all the more powerful because of it. Frédérique, or Fred, as director Xavier Dolan slyly addresses her, lives with Laurence, a well-regarded teacher and author, who eventually announces, beneath the whirring bristles of a car wash, that he is dying. Not of an illness, but of a desire. Desire to finally become the woman he was born to be. Fred, falling prey to the hypocritical murmurings of her lesbian sister, tries to renounce Laurence. But she cannot. She loves his spirit enough to continue loving him as her gender incarnate. Until, she can’t. And back and forth and back and forth like this, as we glide through Dolan’s meticulous and evocative sound, production, and costume designs, across years, across Québec. Despite her efforts to lead a Respectable life with a Normal partner, we sense Fred’s torment, and her inability to let go of the man—now woman—she once held so close.

At their final meeting, Laurence tells Fred that they were fucked from the start. That their love was not meant to last, regardless of the journey the former’s mind and body has assumed. Fred is visibly rattled by such an admission, but it is an important notion. That what for most couples would be a cataclysmic undoing to an otherwise destined longevity, was merely an alternative beginning to an end.

Museum Hours

Take art. Take a man. Take a woman. Take desperation. Take compassion. You have all the makings of a bad Woody Allen Eurotrip, but thankfully there is nary an ex-First Lady of France in sight at the Kunsthistorisches. Instead, there is a humble museum guard, a onetime band manager, who now spends his days ambling along wood-paneled corridors strung with paintings. There is a woman, a visitor, strapped for cash and human warmth, who will shuffle around Vienna, from the museum to bars to the hospital, at his side. Their meeting, although gentle and genuine, is not a passionate one. Outside the obvious human inclination for companionship, their relationship is predicated on a love of inspection, of looking—at art, at people, at the hallowed, snow swept city—one that they share with their creator, Jem Cohen.

The guard’s mere reference to his homosexuality goes as quietly as his soft, enraptured gaze in the Bruegel room. It feels no more revelatory than one of the camera’s drifting observations, as it considers its settings beyond the traditional, conversational focal point. It is natural, and yet somehow, we are so thankful for it. Thankful that their singular rapport will not be encumbered physical resolve. That they can merely continue sharing their histories, their curiosities, their gaze, side by side, as two strangers before a work of art, bound by circumstance.

Frances Ha

Frances Ha is a rare film, the kind whose deceptively simplistic good looks take on varying forms and meanings with repeat viewings. While some may judge it to be a portrait of a bumbling, hapless young artist, others will see it as a treatise on female friendship. It is both, but for all intensive purposes, allow us to consider the latter. “Frances,” Greta Gerwig offered, at a screening back in May, “is as much in love with Sophie as you can be with another person, without wanting to put something inside of them.” Let’s not mince words, then.

Wherever the film finds Frances, chances are, she is pathologically vomiting up disjointed phrases—often, unintentional insults—about her Sophie. If you’ve been there, the sort of possession and fixation you can feel for a best friend is at once unrivaled and indefinable. We don’t quite have a word, a category, for this kind of love, because it is not physical in nature. It is not a “relationship,” and therefore its ardor cannot be explained away like we might brush off a naïf who is irretrievably infatuated with her boyfriend. But not once do director Noah Baumbach and Gerwig disregard or trivialize Frances’s feelings.

She sits, alone, outdoors in Paris, lying to Sophie about her whereabouts, the first time they have spoken in weeks. “I’m going to say something, and I don’t want you to feel like you have to say anything back, so I’m going to hang up,” Frances cautions. “I love you.” The obsolete cellular device snaps shut. No one—to my knowledge—has ever made a love story quite like this one.