I’ve held a fascination for Myrtle Ave. that goes back to 1965. That’s the year my mother and I set off on foot for several blocks east from Flatbush Ave. The Myrtle Avenue El was still in Brooklyn, and I noticed the “dwarf” lampposts beneath the big iron. I recall “My Boy Lollipop,” by Millie Small blaring from a radio somewhere. It’s my only experience with the El, though it and I coexisted for 12 years. I think we got a bus back to familiar territory in downtown Brooklyn and never got on the El.

Flash forward to 1992. For some reason, that year I was lurching around in Ridgewood a few years before I conceived of Forgotten NY and started exploring neighborhoods other than my own, Bay Ridge at the time. I stopped into a Robbins Men’s and Boys on Myrtle and purchased a zip-up black and maroon cold weather jacket with a fleece lining that I still have. I’ve replaced the lining and the zipper and still use it during extended cold snaps.

One thing I found when I began photography for my website forgotten-ny.com in 1999 is still there, this ad at 56-37 Myrtle just east of the WWI memorial at Cypress Ave. and Cornelia St.. After perhaps 50 years the blue, white and gold colors of the ad are still vivid despite facing full sun much of the time. Like Alice’s Restaurant, you could pretty much get anything you wanted at King Arthur’s, which has joined Robbins’ Men’s and Boys in the NYC store graveyard. But my black and maroon zip-up jacket remembers.

Here’s a golden oldie that may be as old as 1892 on Division St. just east of the Bowery at Chatham Square. The Turkish Trophies cigarette brand was introduced in 1892 and sold to the James Duke tobacco enterprise in 1900, which continued the brand till about 1930. The brand distributed card sets featuring smoking cuties, though most women didn’t smoke in public until the mid-1920s. This may be older than a century old. I’m amazed that this ancient ad has held up as long as it has, but certain brands of paint stand up to direct sun better than others.

Not a whole lot of “faded ads” I found in the early days of Forgotten NY survive, but a pair on Jamaica Ave. between Marginal St. East and Vermont Ave. near Evergreens Cemetery and the Jackie Robinson Parkway on a small brick building are still there today, though I selected a photo I obtained in 2007 and enlarged it a bit, hence the reduced photo quality. The ads on either side of the building survive but have faded to the degree that older ads underneath them have started to show through. When I first saw the ad I thought, “Kellobe, an unusual name.” t’s so unusual that it doesn’t exist as far as I know. Instead, it’s a portmanteau of two names: it was opened by two entrepreneurs named Keller and Loeber before World War II.

This is at the west end of Jamaica Ave., a road that could be said to continue out the Orient Point at the east end of Long Island, if you count the entire length of NYS Highway 25. Jamaica Ave. continues west as well, as East New York Ave. and Lincoln Rd., to Prospect Park. However, traffic can’t proceed along it in a through fashion because of one-way restrictions.

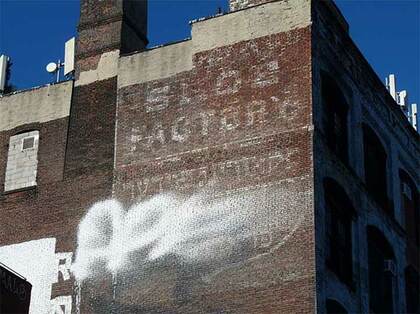

As the years pass, more and more of the “faded ads” that I encountered in Forgotten NY’s early days 25 years ago are disappearing or ravaged by the elements. And sometimes they’ve had help. Take this sign on the side of what was formerly a shoe factory at Hewes and South 5th St. in Williamsburg. The ad was visible from the northbound Hewes St. el platform on Broadway. The ad has faded over the years, and the local youth have set to work, putting their stamp on the neighborhood. The non-English script on the shoe factory ad uses Hebrew characters but is actually in Yiddish. As my friends and Forgotten NY aide Sergey Kadinsky explains, “Although I can speak and understand some Yiddish, you should really thank my grandpa Z. Vaysbukh, who can read and speak the language perfectly.” The line below ”Shoe Factory” reads a word for general production of the factory besides shoes: HABERDASHERY, which means that the factory also used to make socks, shirts, bracelets, pants, etc. And, the bottom line reads Scouring Powder Produkten (products). The factory produced both clothing and cleaning products, likely two separate companies.

Sometimes, the only thing that keeps ads painted on walls from fading into oblivion is the quality of paint used. Can it stand up to pollution and rain and can it withstand direct sunlight? The latter has faded hundreds of street signs around town into illegibility. On Myrtle Ave. west of Broadway in Brooklyn, there’s a perfect example of quality paint that still advertises a business that disappeared decades ago.

Information on the internet is sketchy about L. Salzinger. The Salzinger Building, on which the two ads are painted on either side of the building, to gather attention from passing Myrtle Ave. El riders, formerly held a metallic sign over the entrance, “National Bolt & Nut Co.” I gather that the NBNC was based elsewhere and that L. Salzinger became a franchisee. The metallic “L. Salzinger” sign over the front entrance of the building is newer than the painted ads, so I’d imagine Salzinger, of whom Google mentions nothing, joined the NBNC after several independent years. But, I’m speculating. The much faded telephone number is a GLenmore 8 exchange.

I was meandering in Rockaway Park not long ago and, when outside Boardwalk Bagel and Delicatessen, found what appeared to be a pair of vintage ads. One showed a Coke bottle with the inscription “Trade Mark Registered December 25, 1923.” It turns out that in 1923, the patent for the renewal of the hourglass Coca-Cola bottle shape was up for the first time. The new mold design carried the patent date of December 25, 1923. Because of this, all bottles produced between 1923 and 1937 were known as Coca-Cola Christmas bottles. It’s possible that this ad was produced in that 14-year period, or this is a faithful reproduction.

Also seen is a worn ad for Bazooka bubble gum. Since the brand was introduced in 1947 the red and blue logo hasn’t changed very much. In 1947, a piece of Bazooka bubble gum cost one cent and by the 1980s, it was a nickel. I’m unaware how much an individual piece costs today. I’d say this ad goes back to the late-1980s.

A recent building teardown at 2nd Ave. and E. 72nd St. revealed this partial ad for Pearline Soap. Though Pearline (pronounced Per-leen) is represented in a number of color advertising cards from the late-19th and early-20th centuries, I’ve found little about the company. Pearline soap, developed by a James Pyle, began appearing as a product around 1877, was trademarked on November 21, 1899, and continued in active use well after the rights to the name was purchased by Procter & Gamble around 1912. Interestingly, P&G had a massive complex in the Mariners Harbor section of Staten Island, so large that the area was briefly known as Port Ivory.

You can see that the corner building that was torn down has a lot of wood construction. Unfortunately, most of the ad was whitewashed at some time in the past, though “Pearline” in blue and white be made out. At one time the ad must’ve been as spectacular as the Reckitts Blue ad that popped up after a teardown in Prospect Heights in 1998, first documented by Frank Jump; that ad was covered by a building soon enough.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)