I still have grand dreams and ambitions. Publish a book and buy my own place? Done years ago. Marriage? Make millions? Let’s not get crazy. It popped into my head to list every street in Manhattan that runs for only one block. My criteria for this project were simple. The one-block street should intersect only the two streets where it begins and ends (or one street, if it’s a crescent and begins and ends at the same street) and shouldn’t be a section of an interrupted numbered street. And, they can’t be honorific street names slapped onto already existing streets. Here’s a sampler from lower Manhattan.

Above, the one-block stretch of Mosco St. between Mulberry and Mott is all that remains of the formerly lengthy Park St. (originally Cross St.), which used to run from Centre and Duane Sts. northeast to Mott. In 1982, the remaining stretch was named for community activist Frank Mosco, who was associated with the Church of the Transfiguration on Mott St. and involved with youth outreach, lower-income housing and the elderly, and organized the Two Bridges Little League. The northeast corner, 100 Mosco (left), is where Frank Mosco lived, and 28 Mulberry, Wah Wing Sang Funeral Home (right), began as the Banca Italia in 1888.

One of the shortest streets in a part of town that has a number of them, Moore St. runs for one block between Water and Pearl north of Whitehall near Battery Park. There was no obvious “Moore” in the area in area records in the colonial era it could’ve been named for, so tradition holds that it was for the many ship moorings along Queen St. (now Pearl). All Manhattan territory east of Pearl St. is built on landfill. An extra block of Moore St. east to South St. was wiped out by the New York Plaza complex in the early-1970s.

A set of subway cars runs on the S-curve at Coenties Slip, which remains a wide, though short, thoroughfare today. A tight turn from Water via Coenties Slip onto Pearl St. necessitated this S-curve.

Coenties Slip was one of the largest of lower Manhattan’s colonial-era boat slips. It’s pretty much kept its old slanted shape. The slip was filled in around 1870. The name “Coenties” is old Dutch as Dutch can be, since it recalls an early landowner from New Netherlands era, Conraet Ten Eyck, a tanner and shoemaker. He was nicknamed Coentje, or “Coonchy” to the British, and over time settled into this spelling. Ten Eyck St. in Brooklyn’s East Williamsburg was also named for him. Another story has it that the name is a contraction of “Conraet’s and Antje’s”: Conraet Ten Eyck and his wife Antje. I’ve never heard “Coenties” pronounced, but I imagine area denizens pronounce it as spelled: “ko-ENT-ees.”

Coenties Alley, formerly Coenties La., is a short lane connecting Pearl St. with the rump section of Stone St. cut off by 85 Broad St. Here there’s a brief break from the towering skyscrapers, allowing a view of 54-story 20 Exchange Place, the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce Building (originally the City Bank Farmers Trust Building), completed in 1931, a feverish era for skyscraper building. Within two years, this building, 40 Wall (the Trump Building), the Chrysler Building, and the Empire State Building all rose.

It’s hard to get photos of some of NYC’s downtown alleys because of everlasting scaffolding; so imagine my surprise when Dutch St. was finally revealed to (partial) sun. Dutch St., a one-block path from John north to Fulton east of Nassau, has been nearly completely shrouded by construction sheds for the better part of a decade. On a downtown foray, there it was in the sunshine, or what little sunshine the behemoth buildings of Lo-Man permit.

According to Sanna Feirstein in Naming New York (she’s right about more streets than the late Henry Moscow is in The Street Book) Dutch St. was named for the Old North Dutch Church, which was at the corner of William and Fulton from 1769 to 1875; the name shows up on maps as early as 1789. (Moscow merely says it was named for the Dutch colonizers of New Amsterdam.)

Dey St. and Broadway in the 1970s

Like its one-block long brother to the south, Cortlandt St., Dey St. was once much longer, but because of the construction of the World Trade Center in the early-1970s runs only for a block, between Broadway and Church St.. It was named for colonial-era Dutch farmer, Dirck Teunis Dey; the road was built through his former property en route to the ferry on West St. Today, a look west down Dey St. gives glimpses of the spiky exterior of the new PATH train terminal, referred to as The Oculus, and the glass dome of the World Financial Center, which has a climate-controlled lobby area in which you’ve been able to find several palm trees for the past few decades.

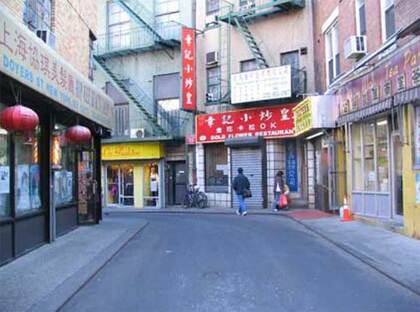

For a one-block street, Doyers St. is unusual in Manhattan, where curved streets are rare: it makes two changes of direction, meaning it goes in three different headings as it meanders from Pell St. to the Bowery. By some chance, the zig-zagging cart path that led to Dutch distiller Henderick Doyer’s tavern has been preserved in situ. The street’s the site of the long-running Nom Wah Tea Parlor. Recently cars have been barred as it’s now open only to walkers, cyclists and scooters. Doyers has been called the “bloody angle” from Chinese gang wars that have erupted along its length over the years.

Twenty or so years ago, Benson St. was a dead end, not a “one and done.” However, a narrow section was opened north to Franklin St. According to both Henry Moscow and Sanna Feirstein in their Manhattan street name chronicles, Benson St. is named for Egbert Benson (1746-1833), NYC’s first attorney general, a delegate to the Continental Congress, and a founder of the New-York Historical Society. Though the name appears to be English, the Bensons were among the first Dutch immigrant families to settle in Manhattan; a Brooklyn branch of the family settled in what is now Bensonhurst in Brooklyn. ( Feirstein erroneously has the street name as “Benson Place.”). The family’s legacy in NYC is far-flung: Egbert Benson is buried in Prospect Cemetery in Jamaica, Queens, while the Benson family’s large holdings in southern Brooklyn are remembered by the neighborhood of Bensonhurst.

Franklin St., and the Place named for it between Franklin and White Sts. west of Broadway, have been there a long time. This Dripps atlas from about 1867 shows it already in place, and every street on this excerpt also remains in place. Before the street was named for the Philadelphia polymath who proved the usability of electricity, stove inventor, editor, political activist and ambassador to France, Franklin St. was, mystifyingly, called Sugarloaf, or Sugar Loaf, St. The name likely had to do with Sugar Loaf, a town and a mountain in Orange County, New York. According to legend, in winter the mountain resembled “sugar loaves” sold before cubes or granulated sugar became the norm.

I’m not sure Ericsson Pl. should count as a “one and done,” as it’s a renamed one-block section of Beach St. between Hudson and Varick, facing the Holland Tunnel approach ramps. However, it gets its own street signs and is unaccompanied by Beach St signs at all. It was named for John Ericsson, the Swedish-born designer of the first ironclad U.S. Navy warship, the Monitor. Statues in his honor can be seen in Battery Park and McGolrick Park in Greenpoint, where the ship was built. Ericsson resided on this block of Beach and until recently the outline of his house could be seen next to a torn-down building.

Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)