People say that if you’re bored, then you’re boring. I don’t think that’s necessarily true or perhaps they’re not defining boredom in proper terms. Boredom can also be known as accedia (the “noonday demon” as the Desert Father used to call it), or ennui, if we want to get existential. This kind of boredom can often induce creativity or aimless roaming around the space you find yourself in.

When I lived in a refugee camp during the Bosnian War, I experienced all types of boredom, and can assure you I’m not a boring person. Boredom in the camp is much different from that in the war. In the war, there’s always a looming threat of death but your being just doesn’t give a damn what happens. Contrary to what some may believe, war’s a very dull experience.

Experiencing the depths of boredom as a refugee in a camp is an illusion of happiness. You think you’re free but this freedom is only temporary and uncertain but you also know that you have to keep sane. If your mind begins to meander without any direction and starts to turn against you, you have to snap out of it and bring it back to its origin point.

I wasn’t always bored in the camp, but the instances of restlessness were far too many to single out. They blend together like the memories themselves and create their labyrinthine uncertainties and veracities. But there was one moment that I recall, a summer day in the refugee camp and there was a sense of peace and quiet. This was generally not the case given the fact that the section of the camp I was in housed close to 100 people.

I shuffled across the long hallway and courtyard that divided the rooms and community playroom in search of something to occupy my mind. The summer heat was only contributing negatively to my lack of concentration. I held a key to another small room—a former office—that was converted to a makeshift library. I clutched at the key so hard that I didn’t even realize it left a mark on my palm.

However fake this library was spatially, it housed real books and magazines. They were either in Bosnian or English and featured many authors. I remember reading Bret Easton Ellis’ Less Than Zero in translation, thinking that this L.A. crowd is rather strange for my taste. And yet there was something weirdly and delightfully American about the whole scene that I was hypnotized.

I picked through the books and magazines but my listlessness was a barrier to finally making a choice in reading material. I don’t think this feeling had anything to do with the camp or the circumstances but with a rather short attention span and a lack of patience I had, and in many ways, still do.

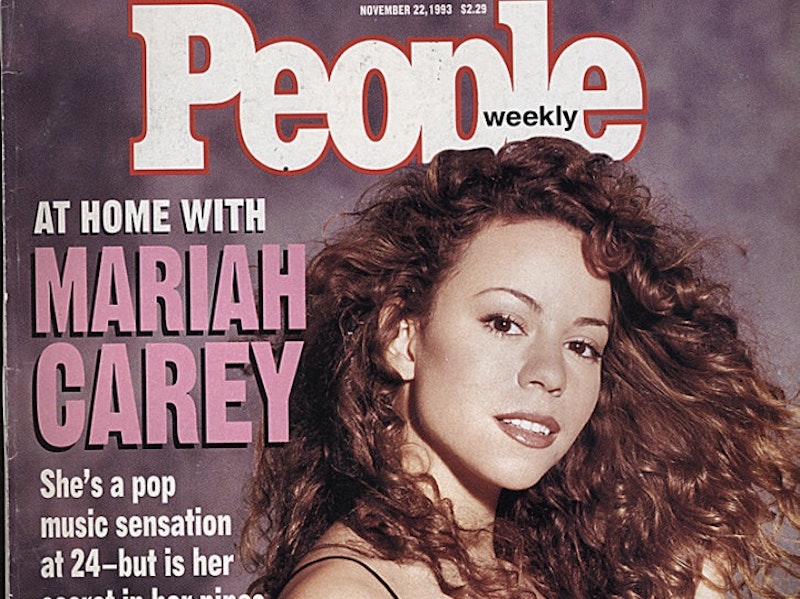

My fingers carefully touched each book as if I were determining what to read based on the weight and texture of the paper. Big printed letters helped too. On a big magazine pile, there was a single copy of People magazine, dated November 15, 1993. By that point, I was in the camp almost an entire year. I wasn’t sure who donated the magazine or where it came from—most likely from the offices of The Prague Post that some Americans brought in. On the cover was a photograph of an attractive and mysterious looking young man, who turned out to be the American actor River Phoenix. I was intrigued by this young man who, in the photograph, obscured his face with his hands. The title of the cover article was “River’s End,” and the subheading read as follows: “River Phoenix was young, idealistic and full of promise when he died at 23.”

I didn’t read an entire article. I spoke English but still had some trouble comprehending every word and meaning without the use of a dictionary. But I could piece together that it was Halloween night and that the “costumed revelers” were gathering around the door entrance to the Viper Room, which was located on L.A.’s Sunset Strip. I kept repeating those words L.A. and Sunset Strip, as if by some odd incantation, I would magically appear in California.

Something strange was happening in front of the club: a man was thrashing and flailing and nobody seemed to have noticed. I continued reading the article: “But no one seemed to recognize the star of Stand by Me and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade… By the time he arrived by ambulance at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center at 1:34, the actor was in full cardiac arrest.”

I was fascinated by this whole event and stole the magazine. I treated it as if it was some prized American relic of highbrow thought. I cut up the photos from the article and glued them to the pages of my daily journal. The otherness and mystique of America exuded from the pages of this glossy magazine. Only later, once I finally arrived in America, would I realize that People is essentially a tabloid magazine, sitting on the piles of other magazines in dentists’ offices and hair salons.

But my later realization and the disappearance of its magic didn’t diminish the immediate experience of intrigue, sadness, and displacement I felt during that summer day in the camp. Through the glossy pages of the magazine, I was thrown into the world of American excess, which was repellent. Yet the strangeness of this other New World—in its freedom to choose or reject the life of baroque excess—was what made it so appealing. I wondered what is this land called America? As the beautiful Miranda spoke: “O wonder! How many goodly creatures are there here! How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world, That has such people in't.”