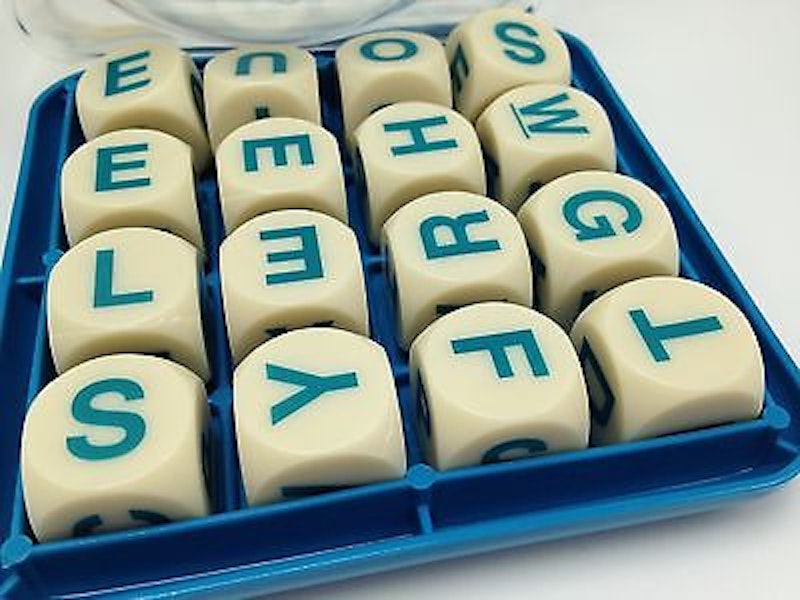

On Saturday night, the couple’s son, a 21-year-old senior in college, expressed an interest in playing Boggle, the family game of choice. It was three weeks into the son’s winter break and he’d made no time for Boggle as yet. They were cleaning the kitchen following dinner when the son, on wiping down the table, stood up straight and threw out his offer. The couple jumped at the invitation, and as soon as the dishwasher was loaded and running and the pots and pans draining in the rack, the three returned to their places at the table, now set up with the game in the middle—the tray of 16 lettered cubes arranged in a grid, under a dome. Writing materials were provided to each—a pen or pencil, a sheet of paper—and when all declared themselves ready the father shook first, turning over the covered tray and giving it a good rattle before setting it down again and lifting off the lid. The mother then flipped over and slammed down the sand timer, marking the official start of play. For the next three minutes the only sound was the furious scribbling of words on paper.

It was on the night of this winter match that the son pulled off a major coup. Not a victory, but something rarer—a blow to the father’s self-regard. It was while the three were taking turns reading off their lists of words, during the second round. The son went last, and to his chagrin, saw his first word struck off the board. (The word was “queasy,” which he spelled with two e’s.) The father, as usual, called the infraction. The father was a walking dictionary who ruled on every questionable word. If he came out for it, the word was allowed; if he came out against it, the word was denied. And because this power was his alone, he was never challenged when his turn came to call out words. If on his list they must be kosher, even the most obscure. In a match one night with his friends the Woods, another couple that loved the game, they accepted on faith, with nary a flinch, his four-point, lead-grabbing stunner of a term for a torso’s covering of armor—“cuirass.” The Woods, no less than his wife and son, bowed before his superior knowledge.

And now, after quashing the misspelled “queesy,” a careless mistake on the part of the son, the father quashed his next word, “queef,” though not for the double e this time. The boy had a habit of making up words in the hope of having one of them stick.

“That’s not a word,” said the voice of authority. “Were you thinking of ‘quiff’? ‘Quiff’ is a word.”

“Well, that may be, but I meant ‘queef.’ Q-u-e-e-f,” said the son, and as he rattled off each letter in the manner of a bright schoolboy, he tapped the corresponding cube with the tip of his yellow pencil.

The father sneered. “What is a queef?”

“A queef is a vaginal fart,” said the son in the manner of one whose hand has been forced. He looked the father straight in the eye and gave a silent laugh.

“Never heard of it,” the father said in a tone that was entirely new for him. To say he never heard of a word meant the word did not exist—or so he had always meant it in the past. But now his tone implied concession, as if to say, “Well, I’ll be darned.”

The son did not quite trust his ears. “So, two points, right?” His pencil hovered.

“Yes, two points,” the father replied, and only then did the pencil move.

Later that night, after the match, as the father was boxing up the tray, his glance happened to fall on the son’s wrinkled score sheet. Mother and son had left the room; only the father remained. He picked up the score sheet and looked it over. There it was tucked away in the upper right corner, directly below the crossed-out “queesy.”

“Queef, a vaginal fart,” said the father, speaking the words under his breath. Now it was fixed forever in his brain, but he didn’t stop there. He pulled out his pen and jotted a note on the index card he carried at all times. The note said simply “dictionary of slang”—a reminder to himself, on his next trip to the library, to look up the word in the trusty Partridge.

A half hour later he went up to bed, and as he was passing his son’s closed door in the darkened hall at the top of the stairs, his mind went back to a distant night when he wasn’t much younger than his son’s current age. He saw it all before him again, right down to the four orange chairs with high backs. He was having dinner with his parents in the kitchen when he let slip a vulgar expression at the table. “It hit me right in the balls,” he said in the middle of a story he was telling his father, who suddenly stopped his placid chewing and turned a scowling face on him.

“Not in front of Mother!” he exclaimed, drawing himself up. All eyes instantly turned to Mother, who truth be told was not some angel who never uttered an impropriety and who might’ve saved the present moment by shrugging off the offensive word. Instead, like a maiden, she cast her eyes down, as if fulfilling the role assigned her—that of a lady with delicate ears. Never had he felt so betrayed by his mother, who sat there mutely, her mouth clamped shut. All the while it hung in the air, that naked word, like something ugly. He shot a final look at his father, and, overcome with shame and anger, threw down his napkin and fled from the room.

In the darkened hall, he marveled now at family life of the present day, when a phrase like “queef, a vaginal fart,” could be casually dropped by the son of the house at the family table, without repercussions. Did his son understand the freedom he enjoyed was only a freedom of recent times? That he and his friends and others their age were living in a kind of new-found Glasnost? He, the father, took no credit for what he saw as a societal drift.

He went on down the hall to his room and found his wife reading in bed. “Had you ever heard of ‘queef’?” he asked as she raised her head in silent greeting. At the impure word she did not, like his mother, cast her eyes to the ground like a maiden. She looked right at him and laughed in surprise. “No,” she told him, with a shake of the head; and there the matter ended.

The following day, at the first opportunity, the father accosted the son with a question. “Do you mind if I ask where you learned the word ‘queef’?”

Grubby with stains, and baggy with wear, the son’s green sweatshirt suggested an answer. Across its front in yellow letters was the name of the son’s expensive college. What more natural place than college to learn all manner of dirty words? The father, sure he had it right, merely awaited confirmation.

In fact, he couldn’t have been more wrong. The son remembered learning the word in his final year of middle school. The father spluttered in disbelief. “Really? In eighth grade? As far back as that?” He saw, not the young man standing in front of him, but a round-cheeked boy trudging to school under a mop of blondish curls. The son went on in a wistful tone, “I learned it watching a South Park show, which had the hero learning it, too. Millions of kids, a whole generation, were introduced to the word that night.”

All of this came as news to the father, who suddenly felt the weight of his years. He saw again the round-cheeked boy, this time sitting in front of the TV, his face aglow in the glare from the screen. At first the sight moved him to pity, to think what the boy was being fed. But the boy himself was laughing wildly, and finally the pity seemed misplaced.

When the son went his way and the father was alone, he imagined a night of Boggle with the Woods and their stupefaction at one of his words.

“Queef? What’s a queef?”

And then he told them, as casual as can be.