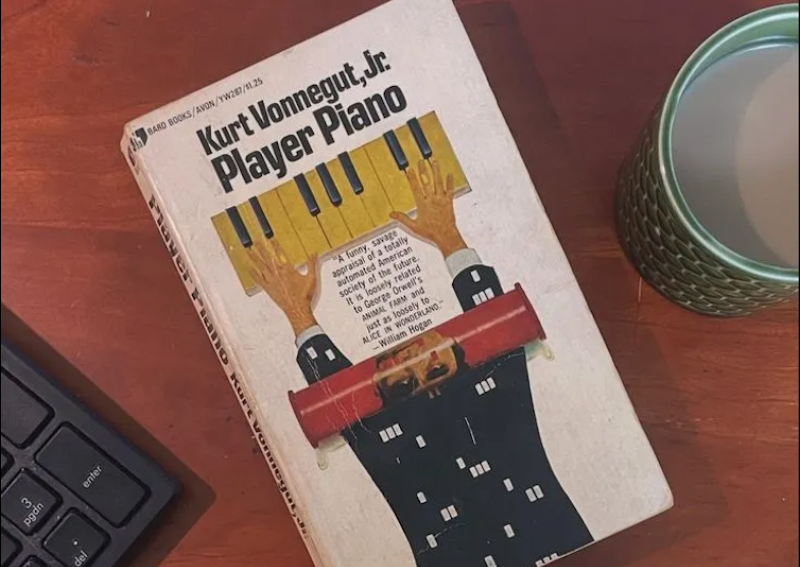

Player Piano was published in 1952, the first novel of a 29-year-old former journalist who’d quit a well-paying job as a General Electric publicist to dedicate himself to writing. The young author, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., was inspired to write a futuristic satire by what he’d seen at GE’s plant in Schenectady, New York.

Set after a third world war, the book follows Paul Proteus, the manager of a great automated factory called the Ilium Works. Named for its location in Ilium, New York, the factory’s an emblem of its times: this is an America in which mechanization’s thrown almost everyone out of work, except for a cadre of managers and engineers who’re being laid off one by one as technology advances.

Proteus drifts through life, as his ambitious wife schemes for his advancement within the corporation. Meanwhile, a Shah visits the United States, seeing this brave new world from an outsider’s perspective. Between him and Proteus, we see more and more of the problems with this world, in which most of the male population’s employed in government-run make-work programs.

Slowly, Proteus grows dissatisfied with the world around him—a world in which artisans have their techniques and movements recorded by computer and then re-enacted by machines, just like a player piano, the production process automated so that the human individual’s eliminated. Proteus’ enlightenment takes about two-thirds of the book. Then he comes in contact with rebels against the system.

Less happens after that than you’d expect, but the book’s point isn’t plot. It’s about Proteus developing to the point where he can make a meaningful choice about his life and his participation in the system of the world.

That system is essentially the system of the early-1950s, that era’s corporate techno-optimism projected forward into an imagined future. Warning about dangerous trends of the moment is fair enough for a satire. The satire lasts beyond its moment to the extent it cuts deeper, and reflects on something generally human.

Vonnegut warns about mechanization depriving people of the meaning to be found in a good job. That’s a big theme, raising the question of what matters in life. If machines can do everything necessary for society that human labor used to do, then as the Shah asks: “What are people for?”

Vonnegut, with a keen eye for absurdity, has some strong moments developing this theme; scenes at a kitschy team-building exercise he based closely on an actual event at GE, for example. But some of the more general societal critique is undermined because Vonnegut at this early stage of his career isn’t questioning his own society enough.

There’s not much about race in the book, for example—one minor Black character, some use of Indigenous imagery by white characters, and the foreign Shah and his party. It never comes together to say anything about either the fictional future or the actual 1950s, especially since the Shah’s the weakest and most obvious aspect of the story. And gender roles read as an artifact of the early-50s; it’s a problem for men to be deprived of the satisfaction of having a meaningful job, but apparently not for their wives.

You might also wonder how credible it is that there’d be a society-wide malaise caused by a lack of work. Did everyone in the future (or in 1952) really find so much meaning in their jobs? Even if so, why not find an alternate source of meaning, in family or community or art?

Vonnegut’s technocratic future is interesting, though: a small group of oligarchs work with a government who taxes their machines heavily enough to pay for the employment of much of the population in government work crews. Why have work crews if machines can do human work? Vonnegut channels FDR’s WPA; unceasing technological plenty becomes indistinguishable from the Great Depression.

What makes the book work is Vonnegut’s prose. It’s lean and precise, avoiding extensive descriptions of the future in favor of dialogue and simple action. It uses irony deftly. And there’s a strong, vigorous rhythm, even when Paul himself isn’t especially strong or vigorous.

This is a book about a systems man who learns how to make his own choices, but who for much of the book is passive. He’s still interesting, though, because his observations of the world around him show his growth. If there’s a happy ending in an otherwise bleak and ironic story, it’s that he develops into someone able to make meaningful choices at least for himself.

The strong character work makes up for a lack of plot, then, which is unusual for American science fiction at the time. Vonnegut didn’t grow up particularly engaged with the genre, but Player Piano fits in with a field that was exploring new and often more satirical tones. The novel’s insistence on theme above story marks it out as something a little different.

If it’s a book about the early-1950s, it’s nevertheless interesting because even as a young writer Vonnegut was interested in human beings and human truths. Mechanization taking away jobs has been an issue for a long time, almost since the start of industrialization, and is liable to continue to be an issue for some time to come. But this is a book about people, not about machines or futuristic economies.

Is work what makes a human being? If not, what does? What do you do with people who have no immediate use to society? What does it take to make meaningful and moral choices? Vonnegut’s taking on big ideas in this book, and if the result isn’t a major classic, his raw talent makes it worth reading.