There’s a funny bit in Dana Spiotta’s 2011 novel Stone Arabia, in which the narrator explains her brother’s late entry into the local punk pit. “Nik wasn’t really interested in the punk or post-punk music scene that was exploding. He was too old [25], for one thing. [But] LA had to answer for the Eagles and Jackson Browne.” Aside from X, LA’s answer was tepid, unless you dug Black Flag and the Germs, which I didn’t. The rescue from the bloated, cocaine-infused acts that filled stadiums with half-hearted music came via London and New York. As it’s said, that’s why the price of cabbage is the price of cabbage.

I do think, on occasion, of the SoCal output of the late-1960s and early-1970s, a lot of which I loved at the time—and still do, for the Byrds, Flying Burrito Brothers and solo Gram Parsons—but now think is really dated. For example, although a monster album at the time, and one that I owned and played constantly, I don’t think there’s a single song (except “Wooden Ships”) on 1969’s Crosby, Stills & and Nash that I ever want to hear again. Has any group so quickly transformed from massive hippie touchstone to “soft-rock”?

Steve Stills is a good example. His major achievement was helming Buffalo Springfield (despite his tempestuous, and jealousy-fueled feuds with the superior Neil Young), and while “Bluebird” endures, his crown jewel was the understated anti-Vietnam War song “Four Days Gone” from the band’s third and final album. Then he went off to the supergroup, a couple of so-so solo albums, and a last gasp in 1972 with the first Manassas record.

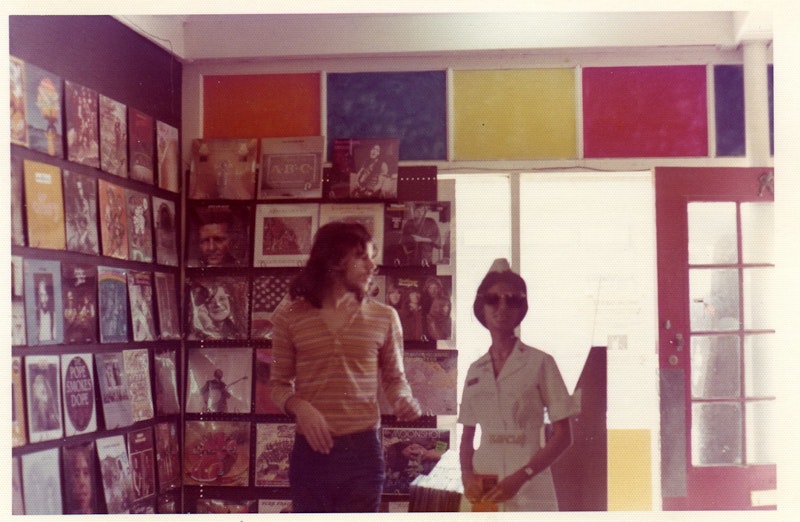

(The pic above, from 1972, shows Huntington’s Kropotkin Records co-owner Rob Witter.)

Chris Hillman (after leaving the Burritos, disgusted with Parsons’ profligate schedule and heroin addiction) collaborated with Stills on the short-lived group, and together they produced one memorable song: “It Doesn’t Matter.” It’s a quiet tune, but the harmonies are nearly perfect, reminiscent of the early Byrds, and it holds up to this day. And that’s despite some really dumb lyrics, like the final stanza: “You might live for the living/Give for the giving, moment by moment/One day at a time/It doesn’t matter, it’s nothing but dreaming anyhow.” That record was in my collection, but “It Doesn’t Matter” was the only song I played after a few listens.

Unlike Stills, whose dissolute lifestyle led to weight gains and losses, and about 100 reunion tours or albums with Crosby and Nash, Jackson Browne’s a marginally more interesting story. He was massively popular in the early-1970s, and his first hit single “Doctor My Eyes” brightened a decreasingly vibrant AM radio, and had fierce devotees. I remember having a friendly debate with a college newspaper buddy (who happened to look a lot like the singer), who made the preposterous claim that Browne’s output—slim at that time—was superior to Bob Dylan’s. I didn’t really take him seriously, which bugged Marc, and he’d try in vain to bait me with the same argument time and again in the fall of ’74.

In a way, Browne reminds me of George Harrison—not for talent, since George is the clear winner there—but for their similar dual personalities. Harrison, from “Taxman” on, often complained about money (“Only a Northern Song,” later, in his twilight with the novelty act The Traveling Wilburys, with “Handle with Care”) and then would drone on about karma, Hindu spiritualism and the immorality of materialism (presumably written in one of his mansions, with his fancy-dan cars in the garage). As I recall, he admitted as much in a Beatles book—or perhaps someone spoke for him—saying he’d mostly live an Indian lifestyle, but would go on expensive binges for a change of pace. Not so different than the men from Muslim countries who travel to Dubai for a weekend of hedonism.

Jackson Browne, who after his initial burst of fame, and money, became a left-wing conscience, showing up at every single political protest in the late-1970s, 1980s, and probably currently, touted as “one of the good guys” in the rock world. After his wife committed suicide in 1976, he wrote a pretty good song, “The Pretender,” in which he lusted for lust and the “legal tender” as “a happy idiot.” Later, there were rumors that he beat up actress girlfriend Daryl Hannah, which was confusing to his dwindling fan base.

Today, he might be a #MeToo casualty, but that movement, at least for musicians, apparently isn’t retroactive. I don’t quite get that: if Dustin Hoffman, who’s 81, can be pilloried for his sexual conduct, why not Jimmy Page, Bill Wyman, Dylan, Steven Tyler and Rod Stewart? And last I heard, the Stones’ “Stupid Girl” and “Under My Thumb” haven’t faced boycotts. (Nor, for that matter, The Band’s pro-Confederacy anthem “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.”)

Anyway, this was a long time ago, so year by year, it doesn’t matter.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955