I’ve always found that there’s something sweetly lachrymose about biographies. For as much as they succeed in allowing us a glimpse into a life or a moment, they’re also records of loss. What they describe is gone forever, a kind of literary outpouring from the sorrowful spinning of what Buddhists call Samsara. Reminders that life, as Kerouac wrote, is a “dream already over.” Why does this feel even more so in a biography of a band like R.E.M.? Robert Dean Lurie’s Begin the Begin: R.E.M.’s Early Years is a masterpiece that should take its place alongside other great band biographies. It’s genre-defining. But what makes it so good isn’t necessarily the job it does recovering factoids or sketching personalities from the past. Begin the Begin is a well-wrought monument to the passing of time. It’s a testament to the loss that gives life its sweetness.

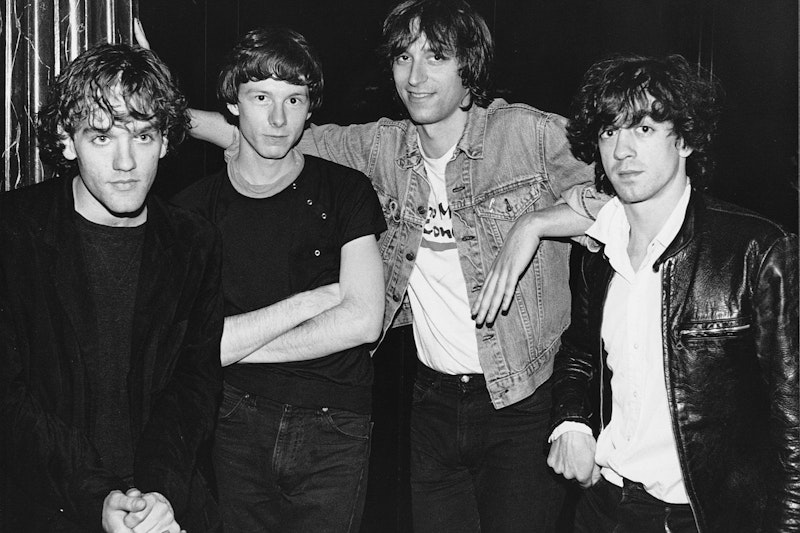

Begin the Begin is a book for insiders, and Lurie is a fan’s fan. True to its name, the book begins with the early lives of band members Mike Mills, Michael Stipe, Peter Buck, and Bill Berry and traces their meandering path from upstart Athens, Georgia party band to one of the biggest acts in contemporary music. R.E.M.’s commercial success and the role they played in popular culture was never assured. Odd turns of event, luck, and the influence of hundreds of friends and early supporters all contributed to making the band the powerhouse high art/pop fusion success that it was. And so Lurie meanders along R.E.M.’s path himself, stopping to linger at the countless little moments that made up the early life of the band.

Ever curious about what Michael Stipe’s favorite brand of mustard was to dip his head in? Ever wonder about the influence playing in Love Tractor had on Bill Berry? Who was the most libidinous on tour? That’s all here, along with other recovered factoids that any fan of the band (or fan of exhaustive pop culture writing, to be honest) will find themselves thankful for. One of my favorite, and not so insignificant, discoveries of Lurie’s is concerning the name of the band itself. Everyone sort of assumes that R.E.M. stands for “rapid eye movement,” the cycles of sleep which correspond to jerky eye movement, low muscle tone, and vivid dreams. But Lurie, after friend and local Athens personality William “Ort” Carlton suggest they’re named after photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard, writes:

“[T]here is a skewed sensibility to Meatyard’s work that is entirely in line with the visual aesthetic Stipe displayed during his early years with R.E.M. Virtually any of Meatyard’s photographs would have slotted perfectly into any of Stipe’s collage-based album artwork. The two artists share a number of overlapping preoccupations: an interest in discarded junk, overgrown landscapes, blurred and/or obscured figures and objects, and a fondness for juxtaposing the vaguely grotesque with the mundane. Meatyard typically asked his subjects (usually his own children) to don ghoulish Halloween masks before posing them in Norman Rockwell-style tableaux... Viewing photo after photo, I get a very strong sense that Ralph Eugene Meatyard must have exerted an influence on the young Michael Stipe—on his art and personality at the very least, if not also his band’s name.”

Lurie concludes “Stipe was thinking of photography in general and Ralph Eugene Meatyard specifically when he lobbied for the name [R.E.M.].”

The recovered facts that make up the life of a group of people in a specific time and place are Lurie’s focus in Begin the Begin. But the clarity gained from such a venture begins to resemble Borges’ The Garden of Forking Paths, and the reader has the strange sense that each repossession equally represents a loss. The detail underscores the finality of the history, and the finality articulates a melancholy ephemerality. Life as a memory of life already gone. Time washing over and through us, which the decay of trends and modes and styles only seem to emphasize.

As Lurie illustrates, R.E.M. was always “ahead of its time” stylistically. Their pitch-perfect blend of arty experimentation and familiar pop structure only came to sound ubiquitous after the band succeeded in infiltrating American popular culture. Compare all the other stuff topping the charts in 1983 with R.E.M.s first full-length album Murmur. It sounds like it could’ve been recorded yesterday. Or in 1994. Or 2010. Which is a testament to the influence the band has had on popular music, especially the genres that came to be known as “college rock” and “alternative rock”.

And yet for all of its ubiquity, R.E.M.’s music will always be rooted in specific time and place. To all the music fans only half-familiar with Athens, Georgia—even more than the B-52’s, Pylon, or Neutral Milk Hotel—R.E.M. are the ambassadors of the town synonymous with punching way above its weight musically. That spirit is especially strong in the band’s early recordings. Lurie writes:

“[I]t seems that the one-two punch of Chronic Town and Murmur captures the spirit of the town the best—perhaps because the band members were still spending most of their time there. The delicately picked guitar patterns, nasal vocals, and lyrics steeped in mystery seem to suggest a self-contained world willed into existence by its inhabitants. When I first heard Murmur, a good four years after its release, these qualities called out like a siren song; they played a larger role in my decision to attend the University of Georgia than I was willing to admit at the time. I had a vision of an eccentric small town somewhere off in the murky woods, a place where a community had fallen under the spell of art for art’s sake and students and scenesters alike flocked to clubs in droves to pogo-dance to quirky, angular art rock. Astonishingly, the place I found largely matched the place I had imagined…”

Lurie does a magnificent job of using the changing town (Athens is much different now, thanks in no small part to the success of R.E.M.) as a kind of synecdoche explaining the development of the band itself. Jerry Garcia said in interviews that the San Francisco that the Grateful Dead came out of largely disappeared by 1968, replaced by a caricature or cargo cult worship of the original forces that informed the spirit of the band. The same could probably be said of Athens and R.E.M., and some old time Athens hardliners might even make the case that R.E.M. itself represented the death-knell of late-1970s Athens post-punk music. Give me Pylon or give me death.

But if the particularities of time and place have faded, so has the way in which R.E.M. “made it.” They rode that final wave of old-style big record deals. And just as they were there to bear witness to an Athens that would be forever changing and forever changed, they’d experience the same when it came to the music industry itself. Lurie explains:

“Even R.E.M.’s business model—the manner, accidental or calculated, in which they ascended from independent college rock band to global pop sensation in slow, incremental steps—has largely disappeared from practice. With the ongoing upheaval in the music industry, artists now tend to be on one side of a great divide or the other; there are those who, like Lady Gaga and Katy Perry, follow the world-domination plan and work from within the ever-dwindling corporate machine. Then there are the vast majority of artists, some quite successful, who either remain on independent labels (or on the indie fringe of major labels) throughout their careers, or follow and even purer DIY approach—using the recently developed tools of YouTube, Bandcamp, and various streaming services to take their music directly to customers.”

What’s gets lost in this dichotomy is the kind of community-fostered live performance art scene, the place and the people who make it possible. Lurie writes, “[T]he story of R.E.M.’s early years... belongs to those of us still afflicted by history. As the participants die and the memories fade, the flame necessarily diminishes.”

And one can’t help but wonder if being corralled into online micro-experiences or force-fed slick corporate products represents the ultimate death of the type of artistic community which gave birth to R.E.M. Perhaps the significance of time and place as necessary coordinates for creating vibrant music has already been engulfed by forgetfulness, like the kudzu smothering the landscape on the cover of Murmur. If you listen to some of their early music, it sounds as if the band was aware of living through that loss. That they were sensitive to the impending decay. Paradoxically, it might be this very awareness which guarantees their continued relevance.