I’m sitting in an enclosed garden in the precincts of Canterbury Cathedral with my friend Jon. It’s one of our favorite places to sit. There’s a wedding on. The bells of the Cathedral are ringing out in an ecstasy of sound, echoing off the walls that surround us, so that it’s impossible to tell where the noise is coming from. The peal of the bells hangs in the air, poised like ripe fruit from some ancient tree, waiting to be plucked.

The Cathedral was founded in 597 AD by St Augustine, who’d been sent by Pope Gregory I to convert the English. Canterbury is the seat of the Anglican Church, and lies at the heart of the English identity. It’s where the English sense of self was born.

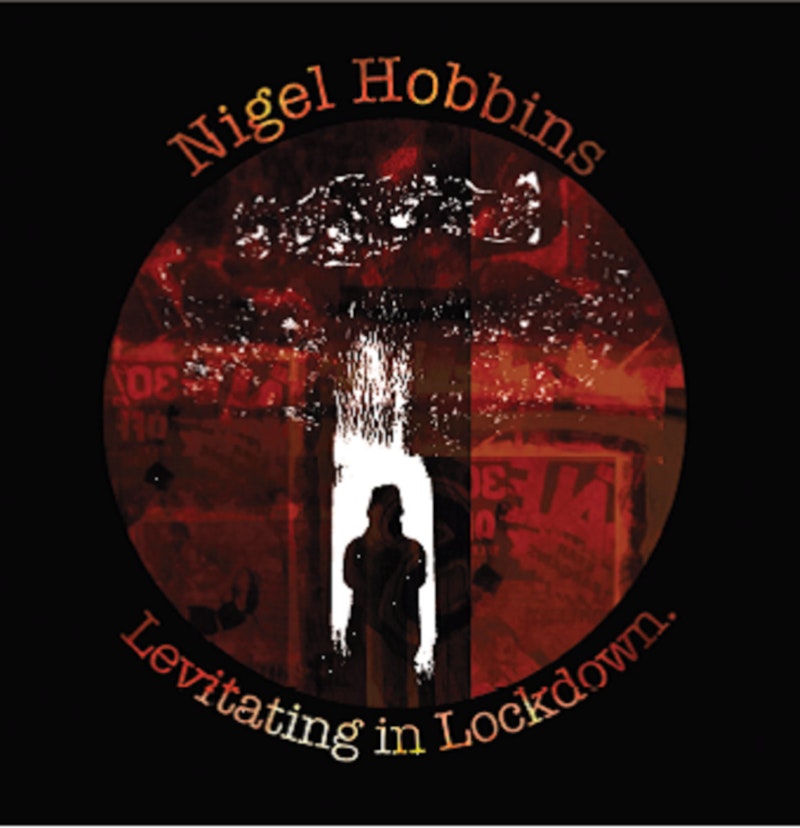

The second track on Nigel Hobbins’ new album Levitating in Lockdown is called “Canterbury Bell.” The “bell” here has several meanings. It’s the bells of the Cathedral ringing out, as they are today, to celebrate some significant moment: a wedding perhaps, or the end of a war. It’s also a wildflower, shaped like a bell. Finally, it’s a beautiful Kent lass, a “Canterbury Belle” in the flower of her youth, heart-stoppingly lovely.

It’s an instrumental, a duet between mandolin and guitar, with a rising, ringing chorus, like the sound of those bells echoing in the Cathedral grounds. Although it’s a new composition, recorded by Hobbins in the heart of the pandemic last year, it’s also immediately recognizable. This is an English tune. It couldn’t have been written anywhere else.

This is Hobbins’ genius. He digs deep into the English soul, the English soil, to find what’s hidden. It’s a kind of musical archaeology. It’s as if these tunes have always existed, and Hobbins has simply found them: as if he has dug them up, cleaned them up, and then presented them to us as if they were new.

The fifth track on the album has a similar quality. Again, it’s named after a flower: the Michaelmas Daisy. Again, it has that air of something found, something old, something profoundly English, something born of the English soil. It’s like a dance tune for an ancient festival, one that lives in the heart of every English person’s soul, immediately recognizable, timeless and yet also brand new.

Hobbins has been doing this for years. From “Glory of a Crown” from his first album, to “Ignore the Rain” from his third, Hobbins captures what’s typically English and turning it into song. For an English person, suffering under the strange spell of these post-Brexit days, this is heartening. To be able to imagine that there’s still something positive to be found in our old country, something worthwhile, something soulful and unique, not yet tainted by craziness, gives us hope of a renaissance yet to come.

The hope lies in the past as well as the future. It’s the sound of English protest in the ghostly and gloriously archaic “Swing Boys Swing,” about the Swing Riots in the 19th century. It’s the sound of childhood and adventure, as well as adult resistance, in the English countryside, in Fighting for the Garden of England. It’s a reminder that the class system is still with us, as we labor under the dictatorship of the Eton Boys, with their plummy, ridiculous accents, their overweening sense of self-entitlement, their politics of blame and division, so well-documented on his latest album:

So if you’re a single mum,

or an old person without a pension,

if you’re homeless or a traveller on the road,

if you’re disabled

or been injured in this nation’s conflicts,

a protester, gay, black or a refugee,

look out for the finger of blame.

Hobbins’ view of English identity is inclusive. Hobbins’ England is a welcoming place, a place of communal identity, where our common dreams may thrive. It’s as light and lovely as those flowers he writes about, as welcoming as a dance tune which calls us all to join in. There are no border guards in Hobbins’ country. It’s the land of the Commons, of the common people with our common hopes, common law, common sense, where property is shared through custom not contract, of the common lands where we hold all our festivals, our feast days, by common assent.

This is the strand that runs through all of Hobbins’ music: a sense of shared identity. He sings of the ordinary people, the Lovesick Brickie and the hired worker. He sings of fairgrounds and skinheads, of men coming home from war, of traditional crafts and times gone by. Of love and loss and sadness. Of celebration. Of our ordinary humanity. These themes apply to all of us: to people all over the world. But Hobbins does it in such an English way, it’s a reminder of who the English were meant to be.

Hobbins is one of the most down-to-earth people I know. I’m a city-boy, an itinerant, a nomad who’s been on the move all his life, and I wouldn’t have it any other way, but knowing Hobbins is to know the reassurance of place, of a music and an art that’ve grown out of an abiding presence in one part of the world. It’s the world his parents grew up in, in Challock, just off the Pilgrim’s Way, one of the oldest continuously used roads in the world. The woods behind his house lead to Canterbury. That was his back garden when he was growing up. And it was here, in a summer house he built himself, in the garden of the bungalow his dad built, and that he has tended all his life, that he made all of the recordings that go to make up his latest LP.

Unlike his other albums, this is Hobbins mainly on his own. His usual method of making an LP is to lay down the basic tracks himself, and then to go from house to house, with his recording equipment, to get the contributions of his musical friends. Lockdown made that impossible. What you get on this album is just the basic tracks, plus the sounds of an old Yamaha DX11 from his store cupboard, which he dusted off and which miraculously sprang into life on being plugged in. It’s a pared-down album from a pared-down time.

But it’s that rootedness that comes out most strongly here, not only the rootedness of place, but the rootedness of family too. His Grandad was a pub singer, with a large repertoire of songs, both Music Hall and traditional, that he used to sing to raise money for poor people, as well as for entertainment; and one of these songs, his Mum’s favorite, that his Grandad used to sing to her when his Dad was away at war, is included on the album. It’s a partly unaccompanied song, sung as a message to those who are away to return home safe and sound.

Lastly, my favorite. “River Fishing,” which opens the album, represents everything that’s characteristic about Hobbins’ music. It is, as its title suggests, a song about fishing on a river. The words veer from practical advice about how to fish, to a lonely invocation of the mood, the soul of the practice. It’s evocative of the English countryside, and of the rivers that still wind their way through our green and lovely land. Specifically, it’s about fishing on the River Stour, the river that shimmies and shivers its way through the city of Canterbury on its journey to the sea. This is the same river that lies in the valley beneath where I live, and that I often visit on my walks. A river is wondrous, cool in the heat, with always a breeze, it ripples and sings to you as you pass by. It’s full of life, of river plants that trail and twist like long green tresses, of moorhens and ducks and the occasional family of swans, of fish that hang in the water, half hidden in the depths by their natural camouflage.

This is precisely the feeling you get from Hobbins’ song. The tune—another one of those characteristic English compositions that are his speciality—carries the essence of the river with it. It swirls and shifts with the current. It sparkles with the sunlight. You sense the life of the river in every note. Short of sitting by a river with a fishing rod, watching the sun go down on a late summer’s evening, I can think of no better evocation of this most solitary of pastimes than this song.

—You can listen to the album here, and his entire back catalogue here.