Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast was filmed a little over a year ago, under pre-vaccine COVID protocol, and it shows—for the first time, in a way that benefits what surely would’ve been another forgettable historical film too toothless and generic to make anyone really happy for more than an afternoon. It’s a movie that people over a certain age ask teenagers and college students working at arthouse theaters if they’ve seen, and what they thought. Beyond being filmed in black and white—and well, as in properly lit—the set and production design utilize the limitations of a virus without a vaccine to tell a larger story in miniature, and again, the result is far more cinematic and inventive by necessity than the film that would’ve been made before 2020.

Beginning on August 15, 1969 with a street brawl between Protestants and Catholics, Branagh’s semi-autobiographical film follows one working-class Protestant family surrounded by violence and forced to consider the impossible: moving to London for safety and leaving Belfast, and so many friends and family, behind. The film ends with the following three title cards over modern day Belfast: “To those who left” and “To those who stayed behind” and "To those who died." The film begins with a geography montage of contemporary Belfast in color, before shifting to black and white as the chaos begins.

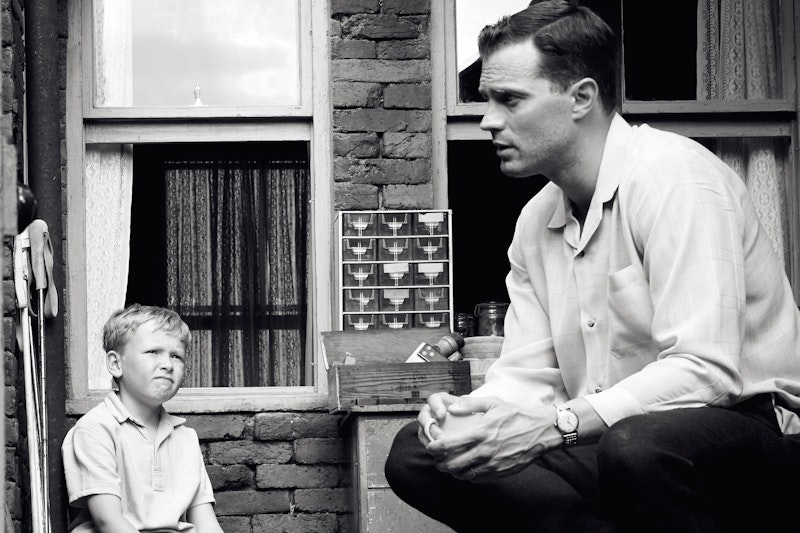

Although the scale of the riots betray the circumstances of production, the small set—one row of houses and a tiny main street—make the film feel more surreal and like a dream, or a memory, and the result is closer to a Wes Anderson movie than the hundreds of bland historical dramas with no visual imagination. Branagh films the family—no surname given—in arch tableau that bring them through a year of living through The Troubles. Ma and Pa (Caitríona Balfe and Jamie Dornan) are good parents, and they anchor their family, and manage to keep the Catholics away. The small scale of the film may make Pa’s confrontation with Catholic agitator Billy Clanton (Colin Morgan) look a bit like the Sharks and the Jets, but once Branagh goes back into the home, everything’s fine.

Except life itself: Granny (Judi Dench) must stay behind when the family eventually leave for London, shortly after the death of their beloved Pop (Ciarán Hinds). In an especially moving sequence, Pop is framed between the ridges at the foot of his hospital bed, with Pa and his son Buddy (Jude Hill) flanking him on both sides. A couple shots later, we see him from overhead in a coffin. Life goes on, even when Dench cries by a bus stop window, watching her only remaining family leave for the big city to get away from all of the bombs and rabble rousers.

I haven’t mentioned Buddy yet, but Belfast is told through his eyes, and with a young boy’s perspective. This is great when it makes the production design exaggerated and larger than life, but you throw a close-up of a terrified child on the screen, you better have a good reason for it. The source material for Belfast offers many, but for a film about something so serious and relatively contemporary, it’s far too balmy in its depiction of violence. Buddy can’t comprehend the details of the Troubles—one good scene features his older friend Catherine, played by Olive Tennant, explaining that “Sean” and “Patrick” are telltale Catholic names, while “William” and “Billy” are signs of a Protestant—and in the absence of any material that really deals with the circumstances of the time, viewers are left with a formulaic family story seen countless times. However true it is, and however close Branagh’s childhood was to Belfast, it’s a movie made for matinee audiences and mild Oscar bait. It’s a good-looking movie, inventive in parts, and funny enough.

Pulling punches and narrowing in on one aspect, one family during a horrible historical period makes sense, but not in the service of this. Belfast’s script is surprisingly jejune for such an accomplished actor-filmmaker, and its rosy eyes (and cheeks) aren’t the problem, it’s that these are roses we’ve seen before, and they’ve long since wilted.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith