Go to any American college and pick up the campus newspaper. Flip to the opinion pages, or maybe the arts section—notably, almost never the political section—and you’ll see the legacy of Hunter Thompson torn and frayed, stretched thin like a t-shirt after its hundredth wash. His is the kind of reputation that lives on even in people who haven’t read a word by the man. Maybe they’re fans of Chuck Klosterman or Neal Pollack, or maybe they’re entranced by Keith Olbermann’s “innovative” mixture of newsroom atmosphere and proudly objective asides. Thompson—the man, the style, the ethos, the legend, and more rarely, the writing—has been mainstream for years, the journalistic equivalent of a bottle of Jerry Garcia wine.* And when people think of “gonzo,” the first thing that probably comes to mind is a mixture of 60s-era psychedelic drug imagery and the serpentine walk of Johnny Depp in Terry Gilliam’s film version of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, the poster for which is another perennial college accessory nowadays.

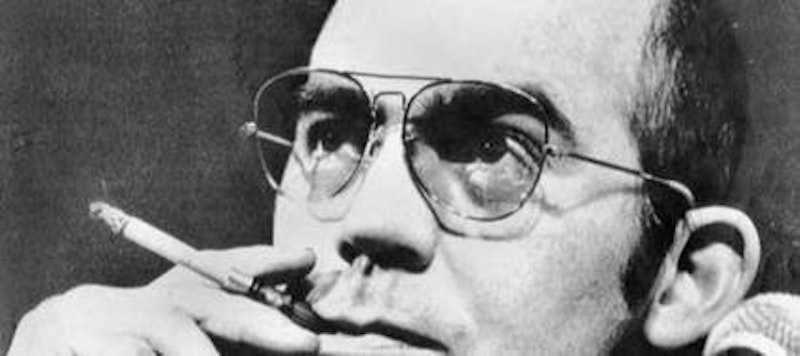

Alex Gibney, whose new documentary Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson opened in select cities on July 4, refreshingly acknowledges in his film that Thompson’s transition from renegade to cliché is the man’s own fault as much as anyone’s. He even pinpoints the moment at which Thompson’s persona swallowed him whole—October 30, 1974, the day of the famed Foreman-Ali Rumble in the Jungle. Thompson was in Zaire to cover the event for Rolling Stone, but chose to skip the fight itself and instead drink near the hotel pool. He’d spent the previous decade habitually bumping up against missed deadlines and blown assignments, but Zaire was the first time that he’d actually dropped the ball and produced nothing. Gibney posits, and is backed up by testimony from Thompson’s friends and ex-wife, that this was the moment when Thompson stopped being a real writer and instead started coasting on Raoul Duke autopilot.

Gonzo is a fun movie almost by default; you’d have to be a pathologically dull person to make a boring movie out of Thompson’s decades-long lifestyle of pills, pot, booze, guns, and fuck-all libertarianism. Thompson’s story encompasses the Hell’s Angels, the Summer of Love, the 1968 DNC riots, the rise and demise of hippie culture, the screaming birth of New Journalism, Vietnam, and of course, Richard Nixon. And his heyday, both as a prose innovator and a public figure, coincided directly with the most talked- and written-about decade in modern American history, roughly 1965 to 1975.

Gibney captures this decade quite well, luckily avoiding cliché simply because Thompson himself managed to do so most of that time. He was older than most of the hippie generation (born in 1937), and was a father by the time the real cultural tumult of the late 60s got underway. He was, despite appearances, a shrewd and hard-working writer, famously retyping The Great Gatsby and A Farewell to Arms in their entirety just so he’d know what it was like to produce a masterpiece. Thompson was aligned with the counterculture’s embrace of drugs, but not with their pacifism or their music; his politics were based more in a general mistrust of all authority than a specific liberal or conservative ideology. Thus Gibney’s impressive list of interviewees includes many of Thompson’s varied friends from throughout the years: Jimmy Carter, Pat Buchanan, George McGovern, Jann Wenner, Jimmy Buffett, and more.

Yet for all the 60s-era trappings, the talk of acid and the frequent gun blasts, Gibney’s documentary is a pretty straightforward piece of work at heart. He focuses primarily on Thompson’s most fertile artistic period, relying on a mixture of Johnny Depp voiceover readings from the man’s writings, interview testimony from his wives, friends, and son, and archival footage of Thompson’s life. No one familiar with Thompson will find much new information here, other than some anecdotal knowledge. (My own favorite anecdote is from Thompson’s 1970 campaign for sheriff of Pitkin County, CO, during which he shaved his head in order to refer to the incumbent Republican as “My long-haired opponent.”) Gonzo functions primarily as an introduction to Thompson, and the best compliment I can give it is that I left the theater wanting to read more by the guy.

This is no small endorsement. I have quibbles with Gibney’s approach—his Errol Morris-style reenactments are particularly out of place and are realistic to the point of near-dishonesty—but perhaps this is the kind of Hunter Thompson documentary that the world needs. We’ve already had two fictionalized and mythologizing accounts of the man’s craziest elements (Bill Murray played Thompson in 1980’s Where the Buffalo Roam), and a forthcoming film of The Rum Diary will surely add to the pile-on. The most revered passage of his writing isn’t the many Nixon takedowns, his groundbreaking Hell’s Angels book, or his infamous article "The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved," but the litany of drugs that Raoul Duke recounts at the beginning of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Thompson’s primary legacy is that of a relic from the acid era, rather than the searing satirist he was in his prime. If nothing else, Gonzo places the emphasis back on Thompson the writer, the firebrand, rather than the time capsule.

Gibney would have been truer to his subject, however, had he borrowed more of Thompson’s penchant for burrowing into the dark heart of his stories. The movie doesn’t ignore Thompson’s late-period decline (he had a mild resurgence with his “Hey, Rube” column on ESPN.com’s Page 2, particularly in the post-9/11 first Bush term), but his movie would be even more culturally useful had he not left out, for instance, the fact that Thompson shot and wounded a woman on his Colorado property in 2000. Gibney acknowledges that his last years were basically an extended bout of substance-enhanced mayhem on his Woody Creek ranch, but this is no small detail to ignore.

Also lost in the Thompson love-fest is the other, non-pharmaceutical reason for his post-70s decline—namely, that his stock-in-trade was that most tenuously inspirational of preoccupations, vitriol. He was political only in the sense that politics and politicians represented the most stultifying and visible version of societal authority, and Thompson’s entire life was a continuing whiskey-soaked howl against any oppositional or controlling force. As such, his writing was never better than when he abhorred something or someone; hatred was the electricity behind his best metaphors and observations, such as this gem about Nixon:

For years I’ve regarded his very existence as a monument to all the rancid genes and broken chromosomes that corrupt the possibilities of the American Dream; he was a foul caricature of himself, a man with no soul, no inner convictions, with the integrity of a hyena and the style of a poison toad. I couldn’t imagine him laughing at anything except maybe a paraplegic who wanted to vote Democratic but couldn’t quite reach the lever on the voting machine.

Or, since this stuff is so much fun to quote, how about his description of a drunken Texan at the Kentucky Derby:

Anybody who wanders around the world saying, “Hell yes, I’m from Texas,” deserves whatever happens to him. And he had, after all, come here once again to make a nineteenth-century ass of himself in the midst of some jaded, atavistic freakout with nothing to recommend it except a very saleable “tradition.”

Thompson was funniest and wittiest when in the throes of disgust, but you can’t stay disgusted forever without becoming disgusting yourself. When Nixon left the political arena, Thompson never had another equivalent adversary again, and it’s no wonder that his existence became more and more secluded and nihilistically bacchanalian. He died at the relatively young age of 67, but he already looked over 80; his was a lifestyle that couldn’t sustain itself, and like his writing, it was a great time for a while until the center could no longer hold.

Gonzo is an encomium, however, not a takedown. Gibney corrects the overly heroic view of Hunter Thompson by refocusing the gaze on his writing, but he would have done an even greater service to future susceptible gonzo-worshippers by further emphasizing Thompson’s decline into self-parody and self-abuse. Anything to make today’s burgeoning, faux-Raoul Dukes realize that Thompson was a true original, and as such, irreplaceable.

*No offense to the excellent and Thompson-inspired Flying Dog brewery in Aspen, who use Ralph Steadman’s drawings for their graphic design; try their pale ale, seriously.

Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson, directed by Alex Gibney. Magnolia Pictures, Rated R, 118 min. Now playing in select cities.