The film The Devil and Daniel Johnston is a masterpiece; I just re-watched it dumbfounded. Here’s what I learned about Johnston and his “art.”

When the late Johnston was living in Austin, hawking the outsider album that would define his life’s work, he was 22. The album was complete; titled Hi, How Are You, its cover is a crude sketch of a whacked-out frog from space. The album reminds me of a science fiction story about laughter. In the story, humor’s an alien experiment, implanted into human beings on a whim. The experiment ends whenever human beings discover what’s been done to them. They enlist computers and they figure it out; at the end of the story, the laughter, all laughter, disappears.

That was Johnston’s predicament. He was a stranger to his own artistic self, unsure what he meant, following mystical leads as if dowsing for water. The disarming childishness of the title Hi, How Are You seemed straightforward to him, I’ll bet. Although I never heard him interviewed about it, I know precisely what he’d have said. “It’s an album about saying hello, in a polite way,” he’d answer, falling into a lisp. “I like it when people ask me ‘how are you?’ Don’t you like it?” In short, he always shifted the responsibility onto the Other or “others.” Because of them, he talks like this. Because of them he’s misunderstood. Because of them he’s among friends. The Other talked through him; out came songs. “I couldn’t write a song if I tried,” Johnston sang, while doped up on the wrong anti-psychotics. Then he added, “doo doo doo.” Get it? He’s not making some kind of fatuous joke. That’s how he created at all times. The seeing, reflective part of Johnston would take a powder as the new song wrote itself down.

You can sense what an eerie wordscape Johnston inhabited. His simplicity is cunning and hard to digest. His output mocks analysis. Ask yourself whether “Hi, how are you?” is meant ironically or not. (Johnston knew what irony looked like, and he constantly mugged “ironic” faces for effect, while speaking in complete earnest. But isn’t that, itself, an ironic attitude?) Is the cloying, ridiculous title meant to satirize socialized routine? Or is it some kind of misconstrued regression that only seems deep because we can’t get over a grown man trying, out loud, to mewl and crawl all the way back to infancy?

Johnston didn’t know. These questions would’ve balked him. His art comes from his own discomfort with using words as tools. His innocence is genuine: he doesn’t grow more familiar with language over time, so it doesn’t age or get sour in his mouth. It remains somebody else’s hand-me-down. In his mind, words are garbage. His idea of love is taking the ugly fragments around him, gluing them together, and signing his name; he sounds, when he’s hustling up new audiences, like a boy giving Mother the birthday card he’s covered in glitter. Because he’s saturated by words, but can’t ever get “inside” of them or grip them right, Johnston fails to see the difference between a song by John Lennon and an advertisement for dandruff shampoo. Yet he passionately refused, like the paranoiac who won’t say certain people’s names, to let himself even think about those evil, awful moments when language zeroes out and means nothing, nothing, nothing. So instead, at Johnston’s pouting insistence, words bloomed everywhere around him.

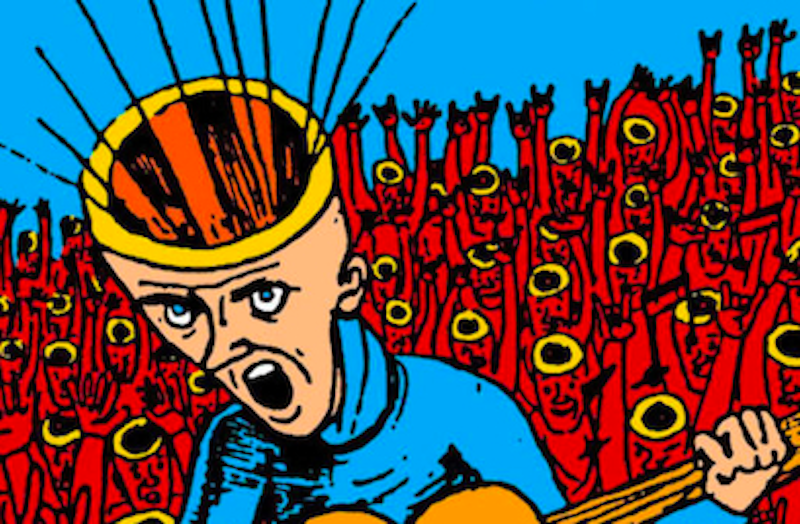

To him there was music in everything. I’m not talking about “music,” in the abstract, or as some totality of diverse genres; in his world, everything becomes connected and it is all (yes! YES!) quite simply the Beatles! He was the Beatles, in his own estimation; his Christian childhood, with its fables of Christ’s Second Coming, helped Johnston bootstrap his way to a manic zenith where he’s the reincarnation of, and heir to, nearly everybody. Then he went even further. He declared that everything he did was art, just to see if that was a magic incantation too. This was an immediate success with his fan club; Johnston broke every lock on our subjective norms, which made him sound sincere. (Who would actually say stuff like that, who’d say everything they did was holy and perfect, unless they were crazy enough to mean it, right?) The audience dreams about drinking in his fathomless sincerity with complete understanding. Give the loony his limelight!

Meanwhile, Johnston equivocated and rationalized these exaggerations. He insisted, to himself, that thinking “I’m a living, breathing epic poem” was the perfect antidote to Satan’s dangerous, chilly insistence that art is a vomit of dead sounds. Even if words did often appear, to him, like a swarming pack of vermin... he thought he could ultimately choose what to believe. He thought his childhood teachers had been right about taking a kindly, positive view of things; faith is nice, hope is nice. Being a “messiah” was Johnston’s Halloween costume, and since the night was always black with devils, he went around in costume at all times. That infected his world with a subtler kind of unreality and madness; at one point, during a prolonged psychotic episode, Johnston thought he was “Casper the Friendly Ghost.” You couldn’t have “snapped him out of it” by pointing out that Casper only exists in comic strips and cartoons. Try asking, “How can a living person be a cartoon?” and he’d answer, “If I’m not a cartoon, what do you call the comic strip I’m living in?”

Johnston ended up paying for all those condescending awards and television spots. When nobody confronts you with a greater reality than your own sandbox can hold, the castles in it cease to be whimsical. Instead, they confine you. Johnston became a prisoner of his own caricatures because we were so determined to indulge them, keeping our own “pedestrian” views about life out of his way.

Johnston’s tragic arc gives the lie to the pseudo-Nietzschean philosophy (brought to the mainstream by hippies and the Beats) that you can dig everybody’s unique perspective, no matter how extreme it gets. Because in reality there’s a certain point, for any audience, where sympathy descends into voyeurism. The voyeurs ultimately made Johnston famous. Not knowing what he meant, or how anyone could believe such incredible nonsense, became the reason urban hipsters attended his shows. To them, sincerity is only forgivable if it’s a spectacle; confessions and delusions, for instance, are thrilling things to be honest about. “All my friends were vampires,” Johnston sang at the end of his first decade of fame. You can hear how exhausting it is to always be spoon-feeding one’s audience new glimpses of gonzo. The kinds of “friends” Johnston made fasten desperately on outsider artists because they’ve gone numb to more explicable versions of the world.

I can’t reproduce the grainy, kaleidoscopic feel that permeates Jeff Feuerzeig’s movie. It doesn’t just tell us Johnston’s story—in its own way, using the medium of film, it sings along with him. I can appreciate the subtlety of that accomplishment. But I laugh off, without a pang, the idea that Johnston was ever a genius. In our postmodern era, it’s sometimes exciting to thow that term around, even when what we’re really describing is a fortunate, spontaneous, collective phenomenon. “Daniel Johnston” was a group effort. His art meant one thing to him, and something totally different to the critics and fellow musicians who made him notorious. His religious fundamentalism was literal for him; meanwhile, for his audience, their approval was a symptom of their boredom. Johnston would’ve made no friends, and gotten no sympathy, if he’d handed out his music at Faith Festivals. His niche would’ve been diluted by other acts of witnessing and made to look clumsy by slicker performers.

But he stuck to his people, in the big new indie tent, and became what they wanted him to be: that is, he turned obsessively religious. He also tried to fit in. He squandered his talent working with other musicians whose creative processes were nothing like his own. The drugs they liked to do made Johnston overbearing, at first, and then incoherent. The cities they wandered around, a la Baudelaire, were dark, sleek, disorienting places; Johnston was in freefall the whole time he was bumming around in New York. His performances there (and there weren’t very many) tended to last around 10 minutes. That’s because the world’s biggest cities make the people in them feel anonymous and invisible. Anonymity frightened Johnston so much he went mute. All he’d ever known were small towns where his smallest tics were big deals.

Did he turn things around? Did he beat a retreat, record more albums, refine his approach? Did he experiment, did he evolve? No. Johnston wouldn’t reflect on his predicament, or make a study of himself, no matter what. This refusal pre-dated his art; it was a defense against his bipolar mood swings, just like his art was a defense that externalized his demons. But mourning his decline is unfair to him. Sometimes the artist who becomes the voice of his generation, for one profound and bruising instant, gets exalted by accident. The mad ones, in fact, are always just accidental spokesmen. Their greatest desire never varies; they long for the paradise of normalcy. Kurt Cobain wanted to enjoy the sound of applause. Edgar Allan Poe wanted to be rational, his emotions suitably constrained. Antonin Artaud wanted to “give things the shape of my will,” with a show of manly force.

Daniel Johnston? Oh he wanted to marry somebody. His early songs are about settling down with a pretty, devoted girl. That was really all he thought about. His absurdly modest Technicolor dreams were more vivid and unspoiled than anything else “folk music” had going on at the time. He found overnight fame, was celebrated, and then fell apart, as if choking on an excess of purpose. The instant that Johnston really “made it,” the experiment that he was came to an end. Our laughter petered out, first; our patience followed.

In his last decade, Johnston won over whole new generations of hipsters by doing passable impressions of himself. By then all that was alien, curious, and powerful about him had flickered out. He’d even adopted the smooth humility of the professional musician. Johnston became a conventional favorite, threadbare from encores, creatively void. And he lived a long time like that, stable and steady, proof that nobody is beyond our power to cure.