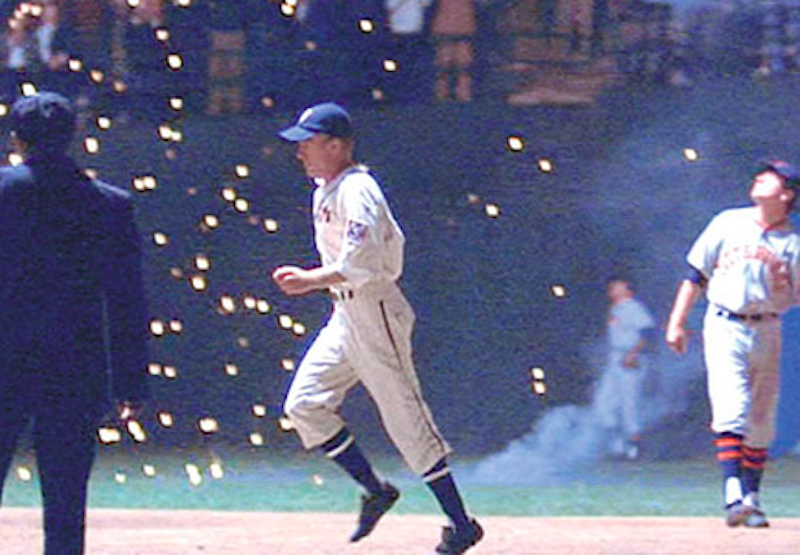

It ends at the beginning, in the light. The light of lightning itself, whose arrow sounds the trumpet and crowns the hero. The light of a suite for brass, organ, and percussion. The light of a staff rather than a sickle, reaping a crop of victory. The light of a rainstorm of artificial light, showering the ground with sparks—and spikes—of mercury and glass. The light of a hero at the plate, rounding the bases and returning home. The light of the best baseball film there ever was, The Natural.

Stark in its contrasts and sometimes contradictory in its use of names, The Natural is a story about light. The titular star is a Nebraskan, not a naïf, whose name shines for a single summer after a long winter of misery and exile. His name is Roy Hobbs (Robert Redford), right fielder for the New York Knights. He wears number 9, a symbol as overt as his blood-stained flannel, signifying both the removal of a silver bullet of a nail from his body and the mortality of his flesh.

His enemies include a gambler, a temptress, a judge, a seductress, and a scribe.

His angel is a mother named Iris (Glenn Close), radiant in her goodness, with clothes as white as snow. She is his muse in Chicago, his maiden in Manhattan. She’s the light at a day game, the burst of daylight at a one-game playoff at night.

The light delivers the pennant to the Knights.

The light delivers a different ending than Bernard Malamud’s novel of the same name. The light delivers a Hollywood ending in which Hobbs has a second act in his American life, eschewing the city for the country; escaping the lure—and lucre—of the East for the modesty of the West; evading the green light across the bay for the sunlight amidst the plains.

The light is the daybreak of morning in America.

The morning is the creation of Phil Dusenberry, whose screenplay is a prologue to the script for

Ronald Reagan’s “Morning in America”: a wide-angle shot of the nation at work, from the lights of an urban harbor to the light above the heartland, culminating in a train carrying the 40th president of the United States.

The light is a remembrance—and a romance—of things past, encompassing the nation’s civil religion and the public’s devotion to the national pastime; recreating, too, those public institutions that grace the landscape with monuments big and small, from ballparks to buildings throughout the city of Buffalo, New York, including the main concourse of the Central Terminal and the neon signs of the Parkside Candy Shoppe.

The light sanctifies the scenery of upstate New York, not far from the Chautauqua Institution and Palestine Park, where a miniature model exists of the Holy Land.

The light reveals the cities and the hills and the rivers and the seas. The light is a path toward replicas of Jericho and Jerusalem, exalting Jesus and the Jewish people. The light runs from the banks of the Jordan to the depths of Jacob’s Well, inviting all to rejoice beside the waters of affusion and acceptance.

The light is a fleeting wisp of glory, where the Knights linger through September. The light lasts for one brief shining moment, while its legacy is everlasting. The light is a scoreboard and bold, signaling kindness and redemption. The light is fanfare for an uncommon man.

About this man, future generations of filmgoers will still say, “There goes Roy Hobbs, the best there ever was in this game.”