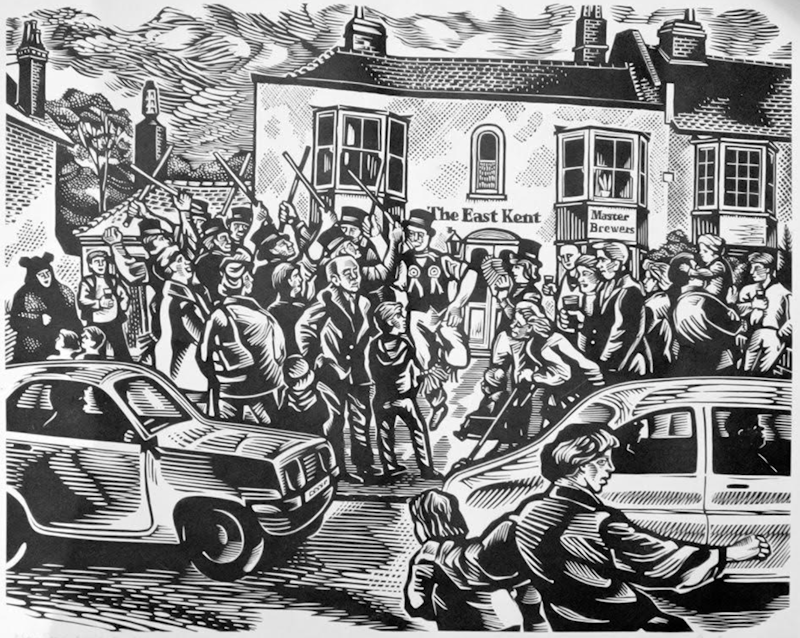

The above image is by the artist Ben Sands. It dates from 1987 and shows a May Day scene in Whitstable, outside the East Kent pub on Oxford Street. You can see the Morris Dancers bashing sticks as they leap into the air. They’re wearing top hats with ribbons and waistcoats with rosettes, with bells tied around their calves. One of them plays a concertina, while the crowd looks on happily, clutching their drinks. You can imagine the joy and the laughter, the old English folk tunes, the rhythmic rattle of the bells, and the clack of the sticks as they crack together.

There’s a brilliant description of a May Day event in Philip Stubbes’ Anatomy of Abuses, from 1583. You can read the original text here, but following is the text in modern spelling:

"First of all, the wild heads of the parish flocking together, choose them a grand captain of mischief, whom they ennoble with the title of Lord of Misrule; and him they crown with great solemnity, and adopt for their king. This king anointed chooseth forth twenty, forty, threescore or a hundred lusty guts, like to himself, to wait upon his lordly majesty, and to guard his noble person. Then everyone of these men he investeth with his liveries of green, yellow, or some other light wanton colour, and as though they were not gaudy enough, they bedeck themselves with scarves, ribbons, and laces, hanged all over with gold rings, precious stones, and other jewels. This done, they tie about either leg twenty or forty bells, with rich handkerchiefs in their hands, and sometimes laid across over their shoulders and necks, borrowed, for the most part, of their pretty mopsies and loving Bessies. Thus all things set in order, then have they their hobby horses, their dragons, and other antiques, together with their bawdy pipers, and thundering drummers, to strike up the devil's dance withal. Then march this heathen company towards the church, their pipers piping, their drummers thundering, their stumps dancing, their bells jingling, their handkerchiefs fluttering about their heads like mad men, their hobby horses and other monsters skirmishing amongst the throng: and in this sort they go to the church, though the minister be at prayer or preaching, dancing and singing like devils incarnate, with such confused noise that no man can hear his own voice. Then the foolish people they look, they stare, they laugh, they flee, and mount upon the forms and pews to see these goodly pageants solemnized. Then after this, about the church they go again and again, and so forth onto the church yard, where they have commonly their summer-halls, their bowers, arbours, and banqueting-houses set up, wherein they feast, banquet, and dance all that day, and peradventure all that night too; and thus these terrestrial furies spend the Sabbath day."

I quote it in full because it’s such a lively piece of writing, which brings the scene to life, despite Stubbes’ disapproving puritanism. He dislikes such overt displays of pleasure, and it’s against this religious criticism that James I issued his Book of Sports, which gave royal approval for such “May games, Whitsun ales and morris dances, and the setting up of May-poles and other sports therewith used, so as the same may be had in due and convenient time without impediment or neglect of divine service, and that women shall have leave to carry rushes to church for the decorating of it.”

Following the English Civil War, with the ascent of the Puritan faction to power, such scenes were banished from the English landscape. They were reinstated with the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. It’s no wonder that the common people grew dissatisfied with the previous regime, and threw their lot in with the Royalist party.

Unlike most holidays, May Day was never a religious festival, dedicated to Robin Hood rather than any recognized saint, as is clear from the following quote, from Bishop Latimer, writing in the 1580s: "I found the church door fast locked," he says. "I taryed there half an houre and more, and at last the key was found, and one of the parish comes to me and sayes, Syr, this is a busy day with us, we cannot hear you; it is Robin Hoode's day; the parish are gone abroad to gather for Robin Hoode." The people didn’t want to attend church on this day, preferring instead to collect greenery for Robin Hood. The young men would create bowers in the woods, made of hazel switch and leaves, decorated with flowers, to which they’d hope to lure their “pretty mopsies and loving Bessies.” Such secret trysts were referred to as Greenwood Marriages—no need to ask the clergy’s permission—and the resulting offspring were known as Children of the May, or Merrybegots. They were considered to be especially blessed, being children of Robin Hood.

Following is a poem from The Play of Robin Hood and the Friar, collected by William Copeland, from his Mery Geste of Robyn Hoode 1560:

Here is an huckle duckle,

An inch above the buckle.

She is a trul of trust,

To serve a frier at his lust,

A prycker, a prauncer, a terer of sheses,

A wagger of ballockes when other men slepes.

Go home, ye knaves, and lay crabbes in the fyre,

For my lady and I wil daunce in the myre,

For veri pure joye.

That gives you an idea of the flavor of the festivities on Robin Hood’s Day. Friar Tuck was a bawdy character, originally attached to Maid Marian before the story was cleaned up for modern consumption in later years. Marian was sometimes seen as the personification of the Virgin Mary. The “huckle duckle” of the opening line is a wooden phallus which the Friar would strap to his groin and expose by lifting his cassock while chasing the girls around. “Trul” probably means “trollop.” No wonder the church disapproved.

In the Celtic countries, May Day was known as Beltane, which may mean “bright fire” in Common Celtic. It was one of four seasonal festivals, the others: Samhain (1 November), Imbolc (1 February) and Lughnasadh (1 August). These have since been adopted by neopagans as one-half of their Wheel of the Year. The other half consists of the two equinoxes and the two solstices.

Beltane marked the start of the summer, when the livestock were driven out to the pastures. Rituals were held to protect them from harm, both natural and supernatural, involving the symbolic use of fire. Animals were driven between fires, and humans would jump over them once they’d died down. Parallel rituals were held to protect crops and people, and to encourage the fertility of the land. The fairy folk, or sith, were thought especially active at this time of year and the goal of the rituals was to appease them. According to Nora Chadwick (The Celts 1970) Beltane was a "spring time festival of optimism" during which "fertility ritual again was important, perhaps connecting with the waxing power of the sun."

The modern adoption of Beltane by neopagans dates to the 1950s, when Gerald Gardner, the founder of the Wiccan religion, and Ross Nichols of the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids, were looking to set up their own festival cycle to replace the Christian calendar.

Both May Day and Beltane might have roots in the Floralia, the festival of Flora, the Roman goddess of flowers, held from 27 April–3 May at the time of the Roman Republic. A similar festival was held from the 2nd Century AD, called the Maiouma or Maiuma. This took place every third year and lasted the entire month of May, in celebration of the sister-brother-lover gods, Dionysus and Aphrodite. Walpurgis Night, held on May Eve in Germanic countries, commemorates the official canonization of Saint Walpurga on 1 May 870. The best known modern May Day traditions include dancing around the maypole, crowning the Queen of May, jumping through bonfires, and drinking copious amounts of ale.

In England it’s most associated with Morris Dancing, a lively, stepped folk dance which is accompanied by the waving of handkerchiefs, the wielding of sticks or the clashing of swords. It has been going in and out of fashion for the last 300 years at least. Almost dying out after the Industrial Revolution, it was saved from extinction by folklorists such as Cecil Sharp and Mary Neal in the early-20th century, and then reinvigorated again during the pagan revival in the 1980s and 90s.

There are a number of different forms and traditions, including Cotswold Morris, North West Morris and Border Morris, this last one the wildest, involving much dangerous-looking stick bashing, leaping and whooping. Traditionally this was done in blackface, but has evolved to keep up with the times, various colored makeup being used as a substitute. Border Morris is the form most favored by the pagan community.

Here in Kent we have the famous Sweeps Festival in Rochester which takes place over the bank holiday weekend in early-May. It’s one of the largest celebrations of Morris Dancing and folk music in Europe. The name derives from the fact that in the 19th century some of the last keepers of the May Day traditions were chimney sweeps. Charles Dickens writes about one such scene in his book, Sketches by Boz, which you can read here.

International Workers Day also takes place on May 1st. Held in commemoration of the general strike in the United States, which had started on May 1st 1886, and which culminated in the Haymarket affair four days later, it was established by the International Workers Congress in 1889 in support of the campaign for an eight-hour day and takes place in countries throughout the world.

In the UK an early May Bank holiday was established in 1978 by the then-Labour government. Though not officially associated with Labour Day, its institution by the avowedly socialist Employment Secretary, Michael Foot, led to some controversy at the time. In 1982, not long after the British victory in the Falklands War, a parliamentary bill was introduced to abolish the holiday and replace it by a new Bank Holiday, more “in keeping with the traditions of England than the workers’ jamboree” as the Conservative MP for Preston North, moving the bill, put it. Opposing the bill was the Labour MP for Preston South who said it’d grown into a celebration of internationalism, describing it as “a people’s holiday.” The bill to abolish the holiday was narrowly defeated.

The link between May Day as a socialist festival, and May Day as a popular people’s festival in honor of Robin Hood is obvious.