Guess the year:

The end-of-a-newspaper story has become one of the commonplaces of our time, and schools of journalism are probably giving courses in how to write one: the gloom-fraught city room, the typewriters hopelessly tapping out stories for the last edition, the members of the staff cleaning out their desks and wondering where the hell they are going to go.

As with most industry descriptions in New Yorker lifer A.J. Liebling’s collection of media criticism, The Press, the differences between the author’s time and ours are largely technological; replace “typewriters” with iMacs, or the paragraph’s later mention of the New York World-Telegram with Seattle Post-Intelligencer or Rocky Mountain News, and we’re as easily in 2009 as 1950, when the above passage was originally written. The Press, published in 1964 and included last month in the Library of America’s second Liebling volume, The Sweet Science & Other Writings, has enough of these universally applicable observations to remain relevant a half-century on, even if its author’s nitpicking focus on his era’s daily print journalism challenges contemporary interest.

It must be said that Liebling’s observations remain relevant largely because his brand of post-Mencken cynicism and distrust of authority never ages; it never goes out of style to call the news biased and newspapers politically suspect. In Liebling’s general diagnosis, papers are poorly written and offer little actual news, but “[n]ews broadcasts offer even less, because often the newspaper owns the radio station, and because television and radio have been pulling steadily out of the news field and regressing toward the animated penny dreadful,” another circumstance where only the economic particulars have changed while the cause for cynicism has deepened. This doesn’t make The Press less valuable, however; indeed, it’s helpful and oddly conciliatory to be reminded that the issues concerning our current newspaper “crisis”—perceived journalistic bias, a relative dearth of proper foreign reportage, charges of elitism, the financial tenuousness of newspaper operation—are nothing new. To read The Press now is to be granted some historical context for the hysterical Chicken Little tone of our current media observers.

Liebling’s book provides an overabundance of context, in the form of his constant block quotes and overviews of the media’s handling of different stories. These range from Stalin’s death to a now relatively obscure piece of Manhattan lore about a taxpayer-bilking poor woman known as “The Lady in Mink.” Regardless of story, the Liebling method is to place each paper’s handling of the issue side-by-side and weigh political allegiances by parsing their respective language. In one of his many well-known aphorisms on the media, Liebling said that “people often confuse what they read in newspapers with the news,” and his close reading and seriatim dismantling of journalistic “objectivity” does provide a valuable service in proving that point. But the fact is that The Press’ big philosophical points are made early on, and the final two-thirds of this book, an omnibus of Liebling’s New Yorker column “The Wayward Press,” drags under the weight of dated discussion.

The book’s early sections, however—the foreword, “The End of Free Lunch” and the first chapter, “Toward a One-Paper Town”—abound with still-relevant wisdom, namely Liebling’s insistence that a for-profit corporate business model runs counter to newspapers’ intended role in society. “I think almost everybody will grant,” he observed in ‘64,

that if candidates for the United States Senate were required to possess ten million dollars, and for the House one million, the year-in-year-out level of conservation of those two bodies might be expected to rise sharply. We could still be said to have a freely elected Congress: anyone with ten millions dollars […] would be free to try to get himself nominated, and the rest of us would be free to vote for our favorite millionaires or even abstain from voting. […] In the same sense, we have a free press today.

Liebling’s perspective, of course, is that of a man for whom a possible alternative to this model is necessarily inconceivable. This is why, to my contemporary sensibility, his rants sometime seem as sophomorically taunting as they are inspired; his industry was a forest of millionaire-owned redwoods, and all he really did was laugh as the trees wobbled and occasionally fell from poor management. (He mentions TV once or twice, but his contempt for the medium—and its relative newness—blinds any serious consideration of its effect on newspapers.) The idea that a new medium could arrive and sound a nearly instantaneous death knell throughout the business was unimaginable, which is why Liebling’s observations on journalism are so amazing to read now. He seems to have unintentionally, unknowingly, foreseen the unforeseeable.

“[A] good newspaper is as truly an educational institution as a college, so I don’t see why it should have to stake its survival on attracting advertisers of ballpoint pens and tickets to Hollywood peep shows,” Liebling states in “Toward a One-Paper Town,” advocating privately-endowed (and thus not reliant on ad sales) papers. In this way he perhaps anticipates multi-private-donor sites like The Huffington Post, while understandably still operating under the assumption, now generally ignored, that in such scenario the journalists themselves would be striving towards some utopian objectivity that the donors’ personal involvement might blemish. But generally, Liebling saw the flaws (he went so far as to call it “the evil”) in a system where information is held hostage not only by the whims and biases of a lucky, wealthy few, but also by the precarious business of the accepted newspaper business model itself; it follows that, whatever misgivings he might theoretically have about the current devaluation of straight-reportage, Liebling would applaud the sheer volume of possible information sources available to us now.

More to the point, it’s hard to imagine the man who refers to the press as “the weak slat under the bed of democracy” crying over the loss of newspapers whose business models doomed them to failure. Had Liebling lived at a time when an even moderately less corporate news-carrying alternative to the newspaper existed, he almost certainly would have preferred it. After all,

[I]t is evil that men anywhere be forced to depend, for the information on which they govern their lives, on the caprice of anyone at all. There should be a great, free, living stream of information, and equal access to it for all.

Regardless of the Internet’s current wild-west state and the uncertainty of how its journalism will be funded, we’re closer to this idea now that Liebling could have possibly hoped for in the 1950s and 60s. With the benefit of hindsight, Clay Shirky expanded Liebling’s warnings in his recent, and much linked-to, blog post “Newspapers and Thinking the Unthinkable.” “For a century,” Shirky writes, “the imperatives to strengthen journalism and to strengthen newspapers have been so tightly wound as to be indistinguishable. That’s been a fine accident to have, but when that accident stops, as it is stopping before our eyes, we’re going to need lots of other ways to strengthen journalism instead.” And as Liebling constantly advocates, the best way to strengthen the medium is through better writing. In The Sweet Science, his famous book on boxing, he recounts a bit of wisdom from Thomas A. Matthews:

Mr. Matthews, who was the editor of Time, said that the most important thing in journalism is not reporting but communication. “What are you going to communicate?” I asked him. “The most important thing,” he said, “is the man on one end of the circuit saying ‘My God, I’m alive! You’re alive!’ and the fellow on the other end, receiving his message, saying, ‘My God, you’re right! We’re both alive!’”

The debate, however pointless, will continue over whether or not the general quality of writing has decreased as a result of the Internet, but there’s no doubt in my mind that the various current methods of online journalism allow for more of this kind of communication than the crumbling paperbound varieties. Newspaper companies are falling because their product simply does not offer the same reader benefits and customizable options that online information sources do. Through increased interaction with newsmakers (lame as Twitter and comment threads can be, they do allow this), immediate access to multiple viewpoints on a given issue, and even through Internet sources’ more open acknowledgment of political biases, we’re moving steadily towards the info-state advocated in The Press. Will paper-obsessed Liebling get his due as a genuine, if curmudgeonly, information-age prophet?

The Sweet Science and Other Writings by A.J. Liebling. Library of America, 1057pp., $35.

A.J. Liebling Saw This Coming

In The Press, published in 1964, the media critic predicted that newspapers' business models would be their undoing.

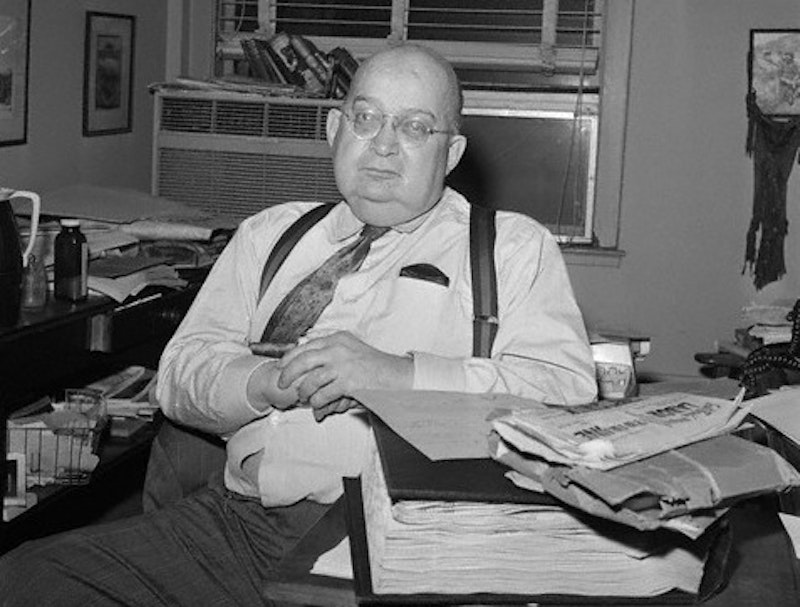

A.J. Liebling in 1963.