It’s been a long time since I’ve been to the movies. Longest stretch in my life, in fact… yessir, and I reckon that it’s due to continue for some time now. Well I did hear that there are movie theaters in Minnesota, but who wants to make the trip? I don’t have a projector at home, any movies, or a home really—just my cabin, my outhouse, and me. It’s not a nice time but it’s what I have. Though I have free reign over the great outdoors, I never feel like going on walks. It’s not exciting, it’s not beautiful, it’s not transcendent. It’s not nitrate film, it’s not black and white stock, it’s not Cinerama, it’s not three-strip dye transfer Technicolor, it’s not glorious eye-popping CinemaScope. Reality makes no sense without direction and editing. Take a look around and imagine Terrence Malick, Miranda July, and Tsai Ming-liang auditioning you for the part of a blind farmer in their new movie (it’s entirely possible, I mean everyone reading this is probably really beautiful).

Imagine Terry in his safari jacket positioning his camcorder directly below your left nostril. Imagine Miranda throwing packing peanuts at you and asking, “Aren’t we all kind of like dead macaroni?” Imagine Tsai challenging you to a staring contest. No one has ever won against him, and while he and everyone else knows this, still they persist. They love losing. One thing I’ve noticed that’s particularly strange about so many human beings is how much they love losing: you see it in the old movies, the silents of course, by the great masters of course. I don’t speak of Chaplin or Lloyd, no—Rex Ingram was my “pageant-master,” along with James Joyce (a friend).

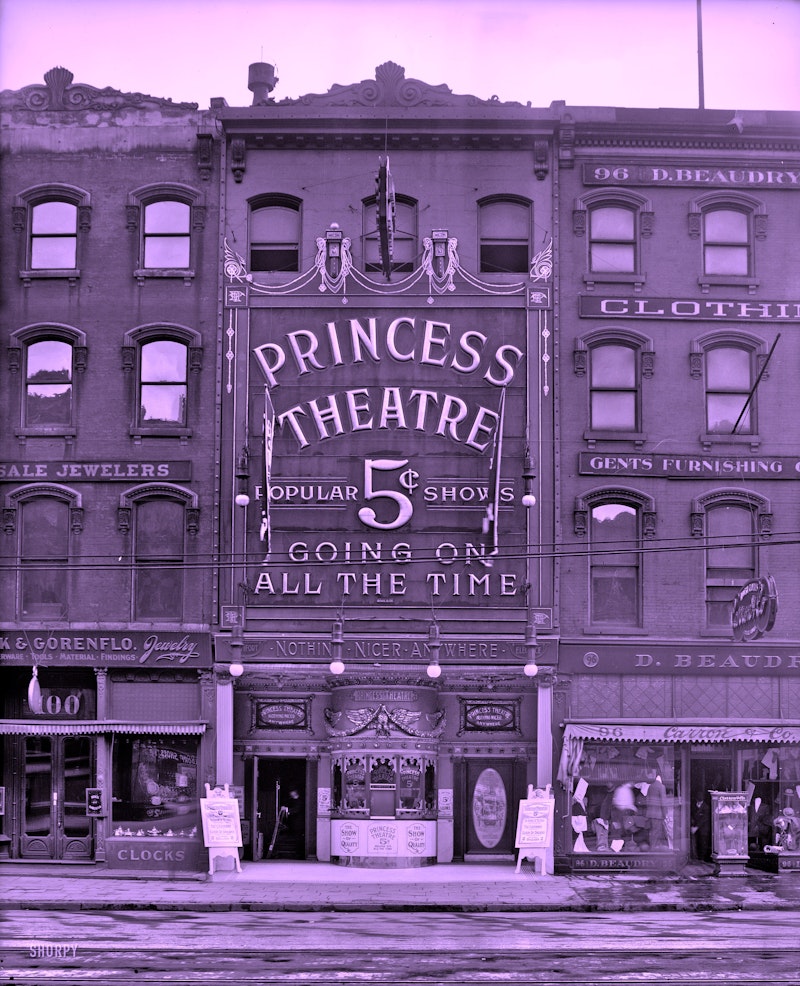

I remember seeing a film of Ingram’s at the 30th St. Nickelodeon in Manhattan. Of course it wasn’t advertised as such, back then the only attraction for movie houses was the peanuts, popcorn, and candy—and of course the novelty of the moving image, a phenomenon many still regarded as practically heretical during the first decade of the 20th century. I took my place in the front row of the tiny, unventilated theater, and waited for the cacophonous hordes of children, criminals, and invalids to come in behind me. They’d often be louder than the pianist accompanying the picture, and I’d have to squawk them, and, in too many unfortunate but necessary cases, I had to spur claw them.

“Bennington,” you may ask, “how could you admit to spur clawing innocent children in dingy turn-of-the-century nickelodeons, much less do it?” Answer: I’m a vitamin ho. No, actually I was one of the world’s first cinephiles. Think about it: who else was arriving on time to these shows? No one. I doubt it was different in France (my ex-wife Daphne says she remembers similar venues in Paris, though without the peanuts of course. They fed their children wine). Yes, it was me, Langlois, Lumiere, and uh… Edison I guess. But I was the first civilian to become interested in movies, and I’ve loved them ever since I first stepped foot into that cramped black box.

You see in a theater like that they had a man that would come every half hour or so to spray a sweet-sweet-sweet disinfectant and mop the floors to mask some of the vomit and fluid smell. Even during the 1918 pandemic, some theaters continued to operate with very risky policies. I was in New York that fall to collect some papers and documents relating to the botched emigration of our family to Ireland in the 1890s, and I couldn’t get out soon enough: the city was alternately empty and full of the dying and the dead, corpses piled three stories high on Canal St. and all the war widows still clinging to windowsills begging for a better tomorrow. There were calls to “wear a mask” back then, but there was more dignity to it.

Even in ignorance there’s dignity, at least sometimes. During that viral pandemic, people were more fractious and distrustful of each other. Every region and town experienced the sickness differently. There was hardly any uniform approach to the cure or ameliorating its most alarming effects. Men, women, and children were dying in the street with distended bellies and lungs full of crystals that looked like they’d come from mustard gas. If you were smart and rich, you stayed out of public indoor spaces for a couple of years. However, given that I am neither smart nor rich, nor was I ever, I continued to go to movies where movies were open.

Big mistake. What was playing in 1918? D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance—yawn. If I wanted to see Lillian Gish sleeping, I’d visit her grave. The “grand master” of film grammar was no such thing, and while I always detested his racist and intolerant films, my issue with him was not political, it was aesthetic. D.W. Griffith spewed poison in the name of God, condemning all foreigners of the Caucuses to servitude, humiliation, and death—but more importantly, he set things in stone. After Griffith, there was no more play in the silent movie houses. There were no more experiments. The films became more homogenous and recognizable in their construction and effect: a close-up of a woman crying, a shot of birds flying away. Montage had begun, and the dream was over.

It’s hard to overstate how radical silent films were even to an uneducated and poor audience in Manhattan through the 1920s. Everyone was still figuring out the seventh art for themselves, and the results were glorious. I remember another matinee turned all-nighter in Times Square around 1925, when sound was just around the corner and those dreaded poof stage actors were about to enter the picture(s), where for a dime I was able to see two features, a newsreel, a two-reel comedy (starring a young Carole Lombard), a vaudeville act (they were old though, really old, a team on their last legs and about to eat dirt and roses), and of course live accompaniment by the neighborhood pianist. You see well into the 1920s, Times Square had its theaters and it had its nickelodeons: they weren’t smutty exactly, but were dirty.

I’ve often speculated that the rest of my family and I were inoculated to the 1918 flu by our regular movie watching habits. As soon as the theaters with cushioned seats opened and we could convince enough neighborhood kids to vouch for us or sneak us in, we went to the movies every weekend. I’m surprised Rooster and Monica haven’t written more about it. We’re some of the only living witnesses to the entirety of film history in America (and some of Europe, but again, what a story! And so little time…). We saw so many films with stars that have all been lost, either in vault fires or shortly after they were screened. Movies were not considered worthy of posterity until well into the 1980s when preservation really began. They were like newsprint—to be consumed and junked in the same gesture.

My favorite hole-in-the-wall theater was the Apraxis in Greenwich Village. No records survive, and I believe everything I saw there was either destroyed or lost. The crowd was older, hipper, but still conspicuously young and dumb. Again, remember: movies were considered a distraction for children and adult idiots. But this was the presaging of the beret and black coffee scene, and they sat in awed silence before the images of Alan Dwan and Horus Huxley, just as they would laugh politely at a Chaplin comedy or a Tashlin cartoon. Perhaps my memory is getting fuzzy—I only remember what the picture was called… Pennies from Hell. Pre-Code, of course. But I remember so little else…

While I’m confident that I’m already immune to the novel coronavirus, I don’t think I’ll be going to any movie theaters any time soon. Not because of the virus, and not because I don’t want to, but it just makes me sad. Movies aren’t what they used to be, and going to the movies isn’t what it used to be. When movies were silent, the audience had to participate and contribute something to heighten the experience. And there was a program! Every movie was a live variety show. For so many decades now it’s just been black boxes to put people in for a few hours before they can go home again to their resentful spouses. I shouldn’t digress, because I know I can cover this topic—the history of cinema in America—in full, it just might take me 50,000 words. So consider this the first arrow in a personal history of the cinema as territory that’ll continue until I judge it to be done. It’ll be a major part of my life’s work.

It’s not for everyone, but I want the variety shows back. I want the peanuts and the candy and the toxic disinfectant. I miss the secondhand smoke and the roar of the projector. I miss the risk of being trapped in a fire hazard theater and being crushed or burned alive. I miss the thrill of seeing a print go up in flames. I miss the stars of Hollywood, and I miss going to the movies. But I don’t miss people who ask if they can pet me. Because it happens every. single. fucking. time. I go to the movies. NO YOU CAN’T PET ME! Only when I ask. Winky face.

—Follow Bennington Quibbits on Twitter: @BenningtonQuibb