Phil Hale is an enigma of a modern artist. He doesn’t have a website, his biography is sparse, and even the hordes of amateur Internet detectives can’t find out much about Hale’s process, life, or art. He’s also one of the most talented modern illustrators and painters that we have, with numerous book covers and the official government portrait of Tony Blair. Despite having a huge body of works to his credit, very few of them appear in any kind of collected format.

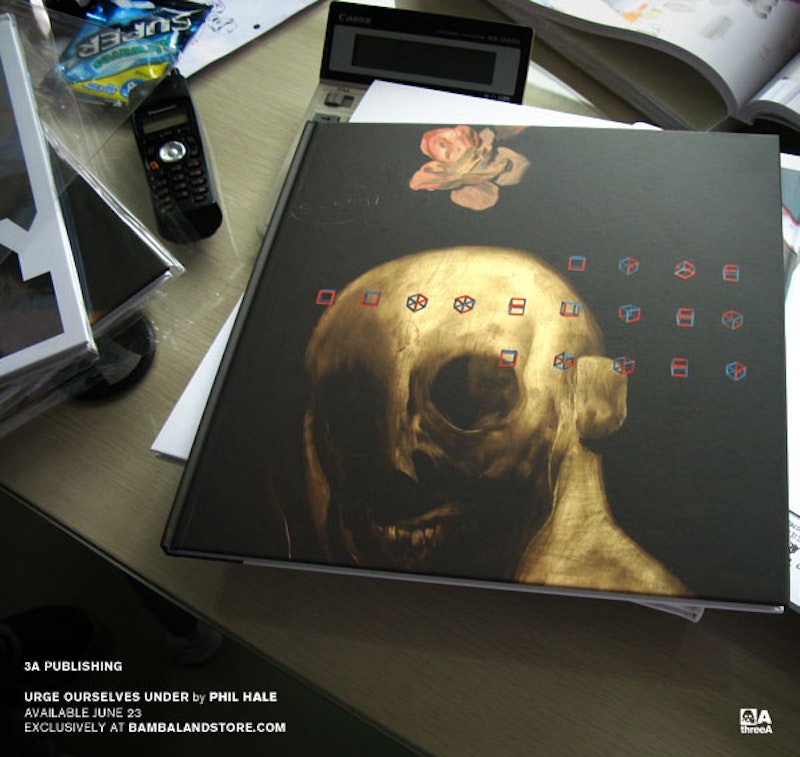

Hale often works in weird anatomical distortions, executed in a very classical, studied portrait style, so his most recent book, Urge Ourselves Under from 3A Publishing, shouldn’t be as much of a surprise as it is. Instead of working with kinetic bodies frozen awkwardly in time, Hale spends an entire 60-page book studying one face. It’s a creepy, obsessive, admittedly self-indulgent collection of work that spans an entire year of study and understanding the same form experiencing similar functions. When displayed, these were shown under the name Toren Schvantzi (or Schvantzt, depending on which part of the press release you read), deepening the weird mystery of the works.

As the series of roughly 30 works progresses, it’s almost like seeing frames from a very disjointed animation. What is obviously a human head has had the front of its surface sheared off—not in any gruesome way, but more akin to what you’d find under the skin of a ghost, or a still of a popping balloon. The sepia and gray skin ripples away, occasionally revealing a hint of bone or eye sockets, but mostly just exposing shadow and the vaguest impression of form underneath. You’re left with the impression that the placid skin of this face is made of water, and someone has just tossed a rock into it. This book captures the record of the 10 milliseconds after this violence. The fact that these portraits are nearly photographic in quality adds to the unsettling, eerie nature of the collected work.

The book format makes it impossible to view these side by side in order to make comparisons and see how the image has changed or shifted, so the nagging question of “What did I just see?” follows you through every page.

Hale seems to be an artist who is uncomfortable talking about his work, and he rarely seems to be photographed in the wild, so the grossly overwrought, flowery interview conducted by Tray Batey concludes that the book seems far out of character with these paintings and Hale himself. Phrases like “moral acuity” and “discernment” are thrown around while Hale’s reply is a simple “yes.” That’s my kind of artist—not shunning discussion, but eschewing the pseudo-intellectualism that some feel necessary to employ when talking about art.

The artist has come under criticism for publishing a book that offers such limited diversity, but what this collection offers is a visceral study in obsession—with one idea, with dense and delicate textures, and with an artist who doesn’t talk a whole lot about his work. I won’t feign enlightenment by claiming that every image offers a new revelation, or presents an intellectual exploration into some new creative frontier, but if the viewer invests just a little bit of time into observation of these works, something very beautiful begins to emerge.