The following quotes come from the letters page of Hex no. 18 (February 1987):

“Half the time I could hardly tell what the hell was going on… No one’s gonna pay 75 cents a month to read Fleisher’s wonderful stories and see them destroyed by Giffen’s trash. I’m sorry to sound so negative, but I’m so darn mad I could chew nails, bullets, and Cheerios all at once.”

“I was shocked! The artwork was terrible! Everyone looks like they have Frankenstein heads!”

“Giffen’s way of doing Hex is ugly… It took me four times to understand each panel…”

“…What have you done to the art? It’s awful… Everyone looks like a bunch of weird stone statues.”

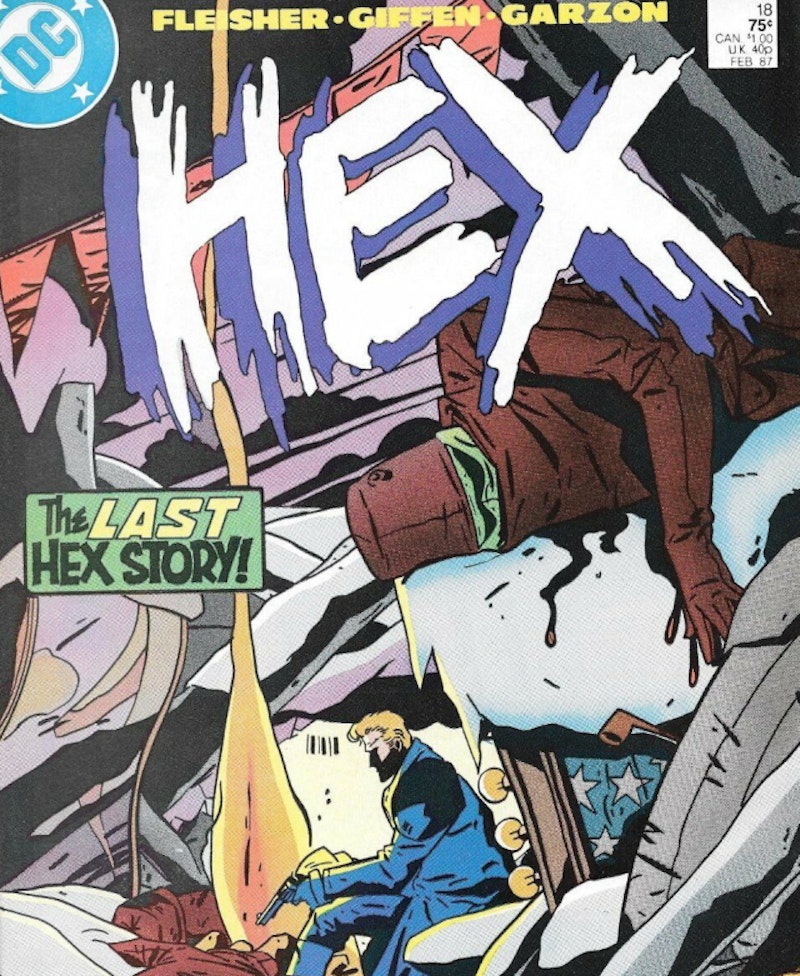

Artist Keith Giffen made some of the most dynamic and confrontational comic book illustrations of the 1980s. His work on the final four issues of DC’s Hex revealed a dystopia that was more than just post-industrial devastation and public health crises. Giffen’s take on Hex was a neurotic distress call from the future. This glimpse at life during a perpetual apocalypse jolted readers with the same sensory overload that plagued the book’s characters.

The name Hex refers to the series’ principal figure, gunfighter Jonah Hex. Up until August 1985 his Old West adventures were featured in a comic that bore his full name as its title. In the final issue, Hex is mysteriously transported through time to a bombed-out Seattle circa 2050. There he becomes a pawn in experiments and schemes hatched by imperialist technocrat Reinhold Borsten. The series simply titled Hex focused on the gunslinger’s attempts to survive the brutal new surroundings and get back to the 19th century.

While stuck in the future he gains a sidekick named Stiletta, a glamazonian biker/drug damaged gladiator who turns out to be Reinhold Borsten’s estranged daughter. Saurian aliens called Xxggs, a chainsaw-wielding assassin, and an ominous global entity named The Conglomerate get in the mix too. The series’ final installments take place underground in a claustrophobic work camp where Hex and Stiletta are pursued by all these villains. Lost in the crumbling subterranean maze, the pair also encounters clandestine rebels and slaves bent on overthrowing Borsten.

Hex 15 through 17 featured pages jammed with nine panels or more (instead of comics' standard four-to-six panel design). Number 18’s story unfolds in a conventional layout but with all the rapid-fire distortion and bloodshed of the previous issues. Several scenes depict a young Hex who has no detailed facial features, a caricature that symbolizes undeveloped identity. These flashbacks occur after he’s wounded while battling the camp’s android security thugs. Bleeding profusely, he hallucinates about his drunken abusive father and childhood days on the frontier.

Under the collaborative guidance of Giffen and writer Michael Fleisher, Hex became the union of a narrative and a puzzle. Intricate scripts were shattered by a kaleidoscopic barrage of barely-separated panels that kept you wondering what was missing, who or what was being depicted, and how close or far away anything was. These were stories from a traumatized world of living ruins where clarity could only be a ghost.