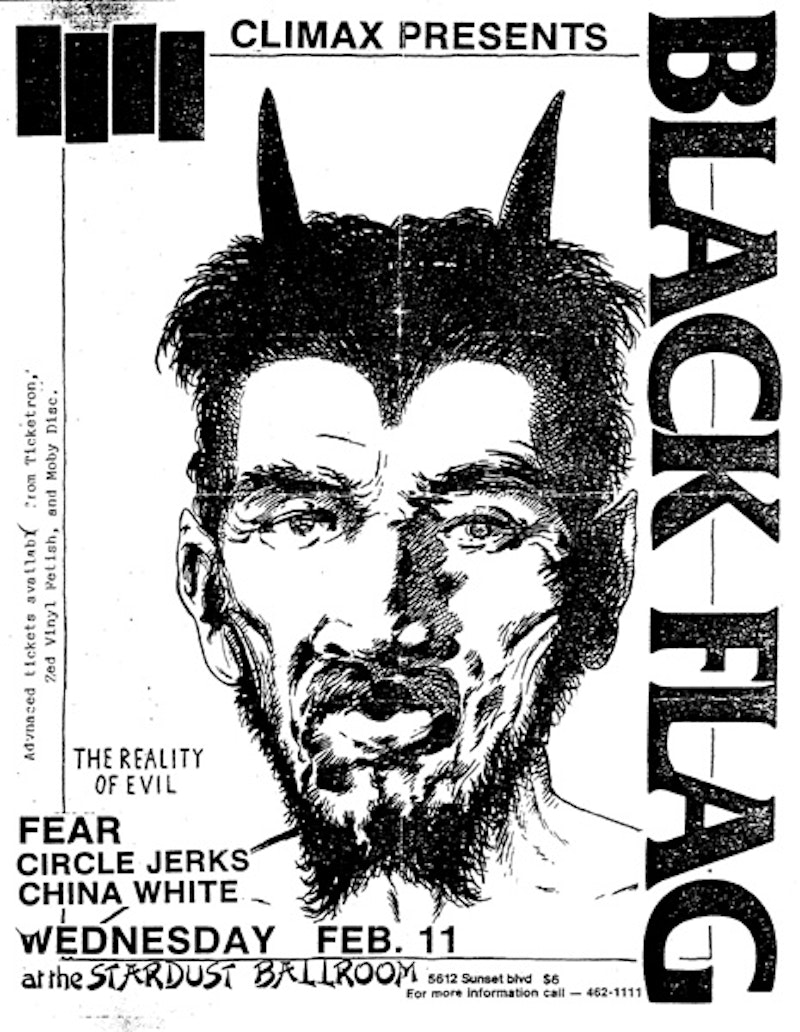

In the winter of 1981, I responded to a backpage ad in Flipside, an independent zine covering the Los Angeles punk rock scene. The ad read: “Videographer needed to document local punk shows.” I’d spent several thousand dollars on a Panasonic video camera and was looking for a way to recoup the investment. I called the number and spoke with Boris, a man with a heavy Slavic accent. He told me to meet him on Wednesday night at the Stardust Ballroom, an old big band venue at the corner of Western & Sunset in East Hollywood.

All I had to do was videotape several hours of punk rock performances and Boris would pay me $300. It sounded simple enough. I’d been a drummer in high school with a love for prog-rock bands like Genesis and King Crimson. I didn’t know much about punk. I’d heard the Sex Pistols and the Clash. I figured punk was just another outlet for teen angst and rebellion, the essence of all rock ‘n’ roll.

The band list that night included the Circle Jerks, Fear and Black Flag. This would be an epic LA show, but I had no way of knowing this at the time. Boris met me outside the venue. He wore a dark sharkskin suit and his face was pockmarked with acne scars. He introduced me to El Duce, a local punk legend who would be my chaperone that evening. El Duce was a menacing singer for the “rape rock” band The Mentors. He was a bald Latino with a ratty beard, sanpaku eyes and a hairy belly protruding beneath a tight t-shirt. He was rude, crass and prone to spitting on and cursing women. (One of his songs included the lyrics, “Bend up and smell my anal vapor, your face is my toilet paper.”) Boris said, “As long as you stay near him no one will fuck with you.”

Boris said he’d meet me on the sidewalk after the show. I followed El Duce into the lobby past a mass of white teens wearing t-shirts and jeans. People gave El Duce a wide berth as he flashed the finger and made fart sounds with his lips. I noticed several skinheads beating the crap out of a longhair near the concession stand. I also had long hair. I turned on my video camera and started taping. My camera would be my invisibility cloak, my instrument of anonymity.

El Duce disappeared into the crowd leaving me without a security detail. I entered the performance space as the Circle Jerks were playing “Live Fast Die Young.” Singer Keith Morris thrashed around stage screaming indecipherable vocals into the microphone. The music was frenetic with distorted guitar, pulsing bass and hyperactive drums. I searched for a vantage point to position my camera. There was an opening left of stage, directly beneath a large amp. I turned on my portable light and carved through the crowd like a snowplow.

There were about 200 people in the audience. Most were calm except a few trying to start a mosh pit. As the Circle Jerks stormed through their playlist, the throng pushed against me and the slam dancing began in earnest. I was struck by a few wayward arm thrusts but I was more concerned for the camera than my own personal safety.

At the end of the set I followed the Circle Jerks backstage. I entered a small room with graffiti-covered walls, a torn couch and several broken chairs. Guitarist Greg Hetson thrust a beer into my hand. He urged me to roll camera as he yelled directly into the lens. “We’re making history tonight. LA is the center of the punk universe.” Someone else screamed, “The Pistols are pussies.” El Duce entered the room, dropped his pants and grabbed his testicles. Everyone was excited, caught in the magnitude of the evening.

That was when I sensed a menacing presence in the corner. He was a short, stocky man with close-cropped hair, muscular neck and piercing blue eyes. He was quiet and tense, oozing rage like a tiger caught in a steel trap. I pointed the camera toward him. He flipped me off and scowled. I turned away, intimidated. El Duce admonished me, “Don’t diss Lee, man. He’ll mess you up.” He referred to Lee Ving, the notorious lead singer of Fear. To this day I’ve never met a scarier human being.

I returned to the auditorium and was greeted by a stench of body odor and stale beer. The room was now packed with thousands of screaming, shirtless fans. My previous camera position was filled. I made a fateful decision, climbing atop the eight-foot high amplifier on the stage. From there I could tape the performance without anyone blocking my view. The sound might be muffled but I was clear of the mosh pit and out of harm’s way.

As Fear began their set, the crowd roared. Suddenly everything was chaos. Their first song was “I Love Livin’ In The City.” Moshers blitzed the stage and smashed into each other like bowling pins. Two beefy bouncers grabbed the aggressive fans and hurled them into the oscillating mass. A band member played an out-of-tune saxophone. Lee Ving stumbled backwards, bodies flying around him. At one point, he looked my way. This caught the crowd’s attention as if they suddenly noticed me for the first time.

I pointed the camera toward the crowd. This was a big mistake. A cup of beer hit me in the chest. Suddenly I felt the amplifier swaying. I looked down and saw two moshers rocking the amp back and forth. Fans cheered. Lee Ving thrust his fist in the air as if to signal his approval.

The amp toppled. I cradled my camera to my chest and prepared for impact. I fell headfirst into a horde of bodies and limbs. People began punching and kicking me. Someone yanked my hair. Others spit at me. I curled into a ball, making myself as small as possible. For some reason I focused on the song that was playing, “Beef Bologna.” I had the thought, “That’s a strange thing to write a song about.”

Someone grabbed me under the armpits and dragged me away. I’ve no idea who it was. He deposited me by the back wall, near the bathroom. My shirt was soaked from sweat and beer. My breathing was labored. I struggled to my feet and shuffled out of the venue. When I reached the sidewalk, I gulped for air. My nose was bleeding but my main concern was my camera. There was a dent in the camera body but it still worked. I pointed at the marquee and took one last shot. Then I staggered to my car and drove home.

The next morning the phone rang at 6:30. It was Boris. He wanted to know why I didn’t meet him after the show. I told him what happened. He wasn’t interested. All he cared was whether I recorded Black Flag. I told him no. He cursed in Slavic. He said there’d been a near riot and a tape of the show would be gold.

He asked if he could get the tape that morning. I told him my camera was damaged and I wanted extra money. He said he would only pay $200 since I didn’t record Black Flag. We agreed on $400. Before delivering the tape, I watched the footage. The performance shots were dark and the sound quality crackled. But the backstage shots of the Circle Jerks and Lee Ving looked great.

It would take a few weeks before my ribs and nose were back to normal. The trauma would take longer to heal. I don’t know why I didn’t make a copy of the tape. Maybe I wanted to put the incident behind me. That would be the last punk show I ever attended.