I’ve just finished reading Down The Highway, the life of Bob Dylan, by Howard Sounes. I spent most of Christmas absorbing it while lying in bed in a post-Covid haze. The reason I wanted to read it is that I’ve been forced to make a reassessment of Dylan recently. This was after the discovery that a favorite song of mine, Death Is Not The End, as sung by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, is actually a Dylan song.

The discovery surprised me because I thought him incapable of writing a good song anymore. Ever since his Christian phase I’d grown to despise him. I can’t stand his weird, croaking, nasal voice, like a frog with adenoids, and meanwhile the quality of his song writing has been deteriorating. I haven’t listened to an album all the way through since Slow Train Coming, the first of his Christian efforts. Not even Rough and Rowdy Ways, which many people said represented a return to form. Murder Most Foul, the 17-minute single from the album, was universally lauded in the press. To me it represented a concatenation of clichés leading to nowhere.

It was a dark day in Dallas, November 63,

A day that will live on in infamy.

President Kennedy was a-ridin’ high,

Good day to be livin’ and a good day to die.

Being led to the slaughter like a sacrificial lamb…

Yawn, yawn, yawn.

It’s like he can’t be bothered to come up with an original phrase any more, or as if he’s too old and tired and his brain isn’t working properly. There’s nothing in this song, or on this album, that makes you sit up in wonder the way his old songs did. He’s looking inside himself, at the thesaurus of his soul, and only finding rehashed lines from old TV soap operas and B movies starring Ronald Reagan. I can’t be bothered.

I used to love him. It was hearing Dylan that set me on the road to becoming a writer. The first record by him I owned was Positively Fourth Street, that bitter lament on lost friendship, which contains the most vicious put-down in the history of music:

I wish that for just one time you could stand inside my shoes

And just for that one moment I could be you

Yes I wish that for just one time you could stand inside my shoes

You’d know what a drag it is to see you.

It’s strange because it’s such a jolly tune, and, I have to admit, it wasn’t really the lyrics that got to me at first, it was his voice, and the sweet, swirling sound of that organ. His voice was so good back then. He’s young, and yet the voice carries an air of ancient knowledge, as if he’s in on some secret I’ve yet to define, as if he’s auguring something about my own future being.

The record came out in July 1965 but I don’t suppose I heard it till I was 14 or 15, two or three years later. After that I just wanted to hear everything he’d ever written. The first album I owned was Blonde on Blonde, which my friend Joe Field told me about. We were both Dylan fans. I liked the fact that Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands covered the entire fourth side. Listening to it was like being taken on a journey to a magical other world where words contained crystallized meaning.

I bought every record then available, and each contained revelations. I discovered that he was the composer of Blowin’ in The Wind and had written the words to Too Much of Nothing by Peter, Paul and Mary. I remembered hearing that on the radio, on Two Way Family Favourites, which was the BBC Light Programme’s link up for British service personnel overseas. The words “the waters of oblivion” struck me even before I knew they came from the pen of Dylan. It was such a poetic phrase.

A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall, from the second album, was the profoundest thing ever written by anyone to my young ears. It sounded ancient, and yet it was new. It resonated with hidden meaning. It was ungraspable, unknowable, and yet meaningful all at once. You could tell he was on a roll as he wrote it. The images just pour out of him. Not a single cliché. It’s hard to imagine that he was only 21 when he first rattled it out on his typewriter in the summer of ‘62. It shows the ability of language to create images out of nothing, and how magical a power this is.

Early Dylan was a force. I realize now that he gained his power from its source code within the folk music tradition itself. Many of the songs repurpose tunes and conventions that come from folk music history. So “A Hard Rain” uses the question and answer structure of such traditional ballads such as Lord Randall, while the tune for Blowin’ In The Wind is almost directly lifted from the old spiritual, No More Auction Block, which Dylan had covered previously. It’s for this reason that some people, including Joni Mitchell, have called him a plagiarist.

Dylan once said, when asked what his influences were, “You open your eyes and you’re influenced, you open your ears and you’re influenced,” which is an acknowledgement that the source of his genius lies somewhere outside himself. It seems to me that this is precisely true. None of us are exclusively ourselves. We’re all made up of the countless sense-perceptions. That includes our influences. It’s out of this chaos that we create our world. The artist is someone who can process this overwhelming mass of information into something that’s never been heard before. This is what Dylan did. He took an old form and made it new. He took old songs, old attitudes, old beliefs and he performed some strange alchemy on them in the crucible of his soul, and came up with songs that make you see things as if for the first time.

As the eponymous character in Inside Llewyn Davis says: “If it was never new, and it never gets old, then it's a folk song.” All Dylan’s greatest works are like this. “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” “Chimes of Freedom,” “Girl From The North Country”: they take something that’s everyday—a storm, a memory, an observation—and add an archetypal twist. When he sings the last verse of Chimes of Freedom, you can hear the urgency and universality of the message:

Starry-eyed an' laughing as I recall when we were caught

Trapped by no track of hours for they hanged suspended

As we listened one last time an' we watched with one last look

Spellbound an' swallowed 'til the tolling ended

Tolling for the aching ones whose wounds cannot be nursed

For the countless confused, accused, misused, strung-out ones an' worse

An' for every hung-up person in the whole wide universe

An' we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing

He’s taken an experience which we’ve all felt; that sense of awe and wonder at the majesty of a thunderstorm, and he’s added a human dimension to it. He’s made it a hymn to all the lost souls on the Earth. It’s so full of feeling, empathy, of direct human connection with the people around him, it’s a wonder that it came from the same pen that produced the bitter dismissiveness of “Positively Fourth Street” or Like A Rolling Stone. And yet these too are full of poetry, albeit of an angry kind.

Obviously something must have happened in the intervening years to shift his perspective. This is where Howard Sounes’ book has proved invaluable to me. It shows the cost of fame. He went from being a brave young poet, out to seek his fortune in Greenwich Village, visiting his idol, Woody Guthrie in the hospital, to being an international superstar of wealth and power, in just a few short years. The girls adored him. He was like all four Beatles rolled into one. All the young poets looked up to him. Mine weren’t the only ears to prick up at his talent and to be guided by him. There must be millions of us around the English-speaking world who’ve drawn inspiration from his words.

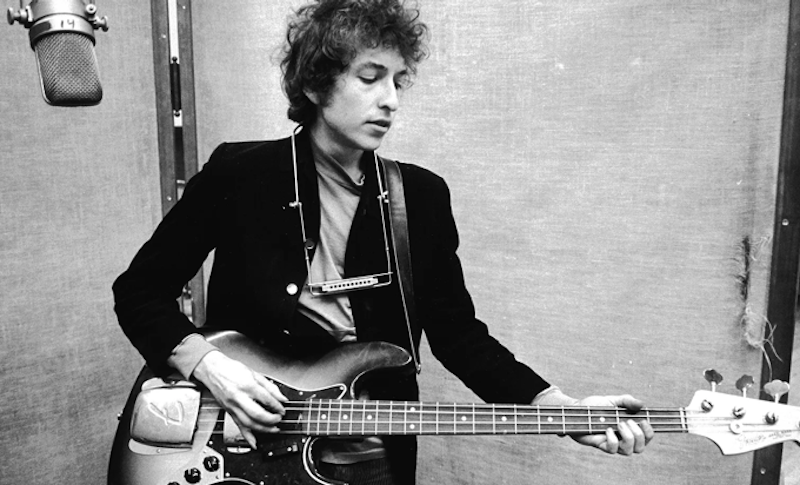

His shift into rock music and symbolist poetry marked another departure and only increased his fame. You wonder now at the voices calling him Judas and booing him on his British tour in 1966. Couldn’t they see how raw and authentic this was? Just as he’d taken folk music and renewed it, so now he was taking rock ‘n’ roll and reinventing it for a new generation. No one had heard poetry like this in the rock format before. Songs like Ballad of a Thin Man, and Visions of Johanna extended the possibilities of what popular music could achieve. Everyone was listening to him and learning from him, from the Beatles to the Byrds, from Allen Ginsberg to Jimi Hendrix. Even conventional poets like Simon Armitagehave acknowledged their debt to him.

But even while this was all happening, while he was touring the world, alternatively screamed at and booed, while snorting speed and drinking too much wine, he was also losing touch with his base, with his real friends, and with the people who’d been with him at the start. He was surrounded by acolytes and obsequious hangers-on all vying for his attention. He couldn’t take out a cigarette without a dozen lighters being flashed in his face. His motorcycle accident, in July 1966, while not all that serious, gave him the excuse to take time off and reassess his life. The result was John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline and a series of Country and Western inspired LPs.

This is when he first began to lose me. I went to see him at the Isle of Wight festival in 1969. He had smoothed out the rough edges of his voice and was trying to sing like Bing Crosby. I was bitterly disappointed. The new songs were dreary and old fashioned-sounding compared with the earlier stuff. Songs like Lay Lady Lay, from Nashville Skyline, seemed so cliche-ridden, lacking in drive, they might as well have been written by one of the professional hacks down in Tin Pan Alley.

Howard Sounes points out that actually he was happy at this time. He’d settled down with his wife and was raising a family. You can see it on the cover photo of Nashville Skyline. He’s looking down at the camera and smiling with a look of contentment on his face. Contentment rarely makes for good art. He was no longer speaking to angst-ridden teenagers like me. His world and my world were so different by now that I could no longer relate to his point of view. This was brought home to me when I read his autobiography, Chronicles, a few years back. There’s a passage in it about how unhappy he was when his yacht was damaged in a storm. How can a man with a yacht speak to the vast majority of people on this earth?

It took unhappiness to bring back the power and urgency of his genius. It was Blood on the Tracks, written while he was splitting up with his wife, that reminded us all of how true and authentic he could still be. There’s a couple more decent albums after this. I liked Desire and Street Legal, but it was not long after this that he converted to Christianity and turned all preachy. I went to see him at the National Exhibition Centre in Birmingham around this time. It was this vast, cavernous hall with tens of thousands of people in it—a long way from the intimacy of the Gaslight Cafe—and little old me, lost in the midst of it all, a thousand miles from the stage. He was doing this weird thing with the songs, restructuring them so they sounded like something else. You could hear the lyrics, so you knew what the song was supposed to be, but the tunes were entirely different. It was like he was showing his contempt for his audience. He wouldn’t stoop to letting us hear the songs we all loved in the way we loved them.

And then, at some point, he stopped the music, and said, virtually the only words all evening: “I don’t know what you think about when you listen to my music, but when you listen to this next song you must think about God.” And his gospel backing group fired up with a gospel hymn about being in heaven and there being nothing to do but to sing God’s praises all day. I thought, “If that’s all there is to do in heaven, I think I want to go to the other place.”

I hated him after that. Everything about him gave me the creeps. His horrible, nasal voice which can barely touch a note these days (he used to be such a great singer). His dreary, cliche-ridden lyrics. His self-satisfied air. His fake references. His awful film making. His constant chasing after money. Selling his back catalogue. Allowing some of his greatest songs to be used as advertisements. His never-ending tour. His theme time radio hour. His book of song reviews. His stupid mustache, cowboy hats and cowboy gear. His ridiculous Christmas album. His long silence when his Nobel Prize for literature was announced. His failure to turn up and to receive the prize with grace and humility. Sending Patti Smith instead, which led to her embarrassment at forgetting the lyrics to “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” That was Dylan’s fault. He should’ve been there singing the song himself.

There’s a sense of betrayal now that all the hopes I’d invested in him have turned out to be false. He’s just another greedy rich man, so full of his own sense of self-importance that he can no longer see the reality of the life around him. And yet he can write a song like Death Is Not The End, surely as good a song as he’s ever come up with. I think there may be one or two more tucked away in his recent catalogue which show that he can still write. I guess I’ll just have to put up with that gnarly voice of his and find out what they are.