Nothing’s worse than the college friend who predicts, in front of all your bohemian buddies, that you will one day teach high school. “You’ll be great at it,” he assures you, a compliment that makes the insult even worse. What he means is this: You’ll be good at explaining obvious things. This same guy was the first person to hand me a copy of Astral Weeks and tell me it was something sacred.

When you write about music, you stand in the shadows of that particular Van Morrison album and the essay Lester Bangs wrote about it. There’s no helping it; what Bangs wrote, over time, has come to define the way a serious critic can explain the mystically inexplicable so well that the rest of us hear something different, forever after, in certain pop songs. The sentences go off like a cannonade:

If you accept for even a moment the idea that each human life is as precious and delicate as a snowflake and then you look at a wino in a doorway, you've got to hurt until you feel like a sponge for all those other assholes' problems, until you feel like an asshole yourself, so you draw all the appropriate lines. You stop feeling. But you know that then you begin to die. So you tussle with yourself: how much of this horror can I actually allow myself to think about?

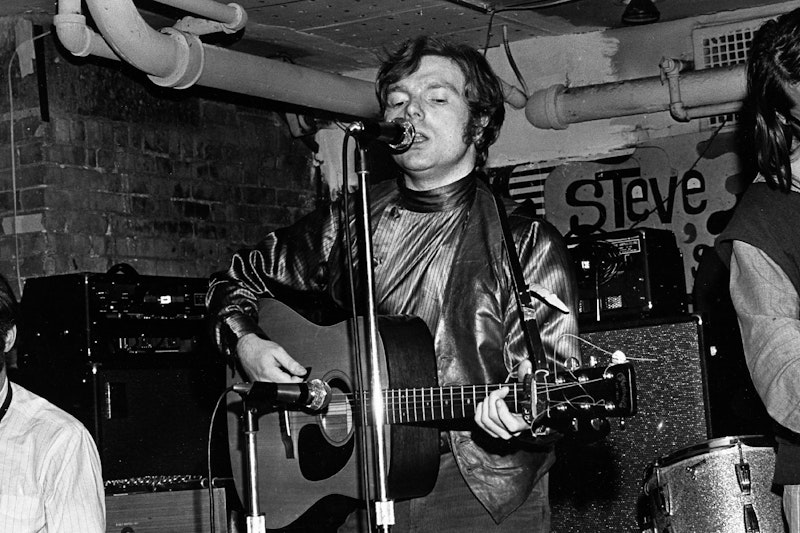

I’m not saying that these sentences, considered dispassionately, actually map all that well onto every track of Astral Weeks. Bangs has his favorites here, and he backs up his claims exclusively with them, instead of trying to explain “Beside You” or “The Way Young Lovers Do” for the sake of completeness. What I am saying is that Bangs radically expanded, by writing one incredible essay, our notion of pop music as high art. Pop singers could now dispense with accessibility. You didn’t have to be The Beatles. People didn’t have to like you. Nothing pleased Bangs more, in 1978, than digging up “a mystical document” that nobody really “got”—enter Van Morrison, in 1968, all dressed up as some kind of New Age Christ—and proclaiming, ex post facto, that it was important.

Bangs’ dictum on the rest of Morrison hangs over us, too: “Van Morrison never came this close to looking life square in the face again.” That’s truer than it is false, but there’s one important exception. In 1970, just two years after Astral Weeks, Van Morrison released Moondance. His progression from one to the other makes sense. Astral Weeks was expansive: it was a psychedelic trip through free jazz and shimmering, archetypal folk. The lyrics juxtaposed grotesque characters with utopian dreams. Moondance was the other kind of jazz: romantic, intimate, and lush, with long blasts of saxophone. Morrison’s album is consequently remembered as one of pop music’s nicest come-ons. It’s generally rated as likable, but unimportant. It’s been damned with faint praise.

Consider, though, how much this one album has to say about love. For example, the first song (“And It Stoned Me”) is about individual pleasure and camaraderie; love before it gets romantic. It’s nostalgic, but the nostalgia isn’t morbid, since the same things could happen again tomorrow: “We just stood there getting wet/With our backs against the fence.” Unlike his musical peers, who were making bitter statements about the end of the hippie era, Morrison is still stoned and loving it. The pastoral exaggerations of Astral Weeks have shrunk down from a heavenly to a human scale. Instead of walking through “gardens all misty wet, all misty wet with rain,” Morrison narrates an ordinary day: “Then the rain let up and the sun came up/And we were gettin’ dry/Almost let a pickup truck/Nearly pass us by.”

What’s remarkable here is the way water remains a vivid symbol of love, even when it’s framed by humdrum events. After the two friends hitch a ride, “the driver grinned… and he dropped us up the road/Yeah we looked at the swim and we jumped right in.” The song is a journey from anxiety in the presence of the miraculous—“Hope it don’t rain all day”—to acceptance and delight (“Oh, the water/Let it run all over me”) and even a sort of quiet renascence (“Stoned me just like goin’ home”) that is more achievable, by far, than Morrison’s fervent prayer on Astral Weeks to be “born again.”

On “Moondance,” Morrison pulls out a set of charismatic moves bandleaders like Louis Armstrong and Bing Crosby had been working for decades. The song swings so insistently, which such a bold, insinuating bassline, that it palms all its complexity like a magician who won’t reveal his tricks. “I’m trying to please to the calling/of your heartstrings that play soft and low,” Morrison sings. His syntax is bizarre, even dizzying, but rhythmically perfect. The meaning leaps and then dawdles right along with the tune. The music is his lover, re-embodied as nocturnal jazz. She possesses him as he channels her. The underlying dynamics are every bit as wild as they are in Morrison’s crazed requiem, “T.B. Sheets,” although this night unfolds in a more confident key.

I was listening to Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest, the new album by Bill Callahan, and wondering where I’d heard something like it before. That’s the quiet power of Moondance, which has countless successors, but never gets the bylines it deserves. Callahan’s unadorned, domestic album has a funny title. It comes off, at first, as a knowing joke about the samey quality of these contented songs, as if he’s apologizing for being pastoral. Dig a little deeper, and the title takes on additional resonance. The shepherd in his vest has everything he needs, in ample supply. He is lucky and free. That’s what Morrison discovered he could be, when the 1960s were over, by tucking himself away in the quenched, unspoiled places of this world. There’s a feeling of perpetual motion throughout Moondance, undertaken by gypsies who travel light: “Together we will float/Into the mystic,” Morrison sings, and he also sings about “the caravan [that] has all my friends.” But this isn’t Kerouac and the singer isn’t running. He’s on his way home, bearing gifts, surrounded by lovers and friends: “And when that foghorn blows/You know I will be coming home.”

The balance of new and old, love and friendship, exaltation and rest, is apt to look easy and dull on paper. But to live it, sing it—this, in fact, is the adventure of adulthood. Lou Reed once described his philosophy of music like this: “Music’s never loud enough. You should stick your head in a speaker. Louder, louder, louder. Do it, Frankie, do it. Oh, how. Oh do it, do it.” Morrison rejects that limitlessness: “Turn it up, turn it up, little bit higher, radio/Turn it up, that's enough." Moondance isn’t an album you have to play incredibly loud, or an album you need to hear every day for a year, or an album that only 40 people understood when it debuted. I still spend more nights blasting Astral Weeks, trying to understand it, than I spend parsing Moondance. But the elder album never completely disappears from view. When you’re ready to finally be happy, it will be there, waiting for you, at journey’s end.