Walter Kirn, the other day on Twitter: “People feel trapped, the poor are poorer, the rich are something beyond historical precedent or normal comprehension, the meth is everywhere, the pain pills too, veterans of endless wars are staring at walls — & our grandiose politicians are on a manic divisive fame & virtue trip.”

Kirn is talking about the moment, not movies, and since theaters have closed, movies can’t effect the moment. Pop culture is frozen, cinematically at least, in 2019. Some people may talk about Nomadland or Promising Young Woman, but these “major” awards season movies will pass through the American cultural colon unnoticed. A movie like Parasite has no opportunity to inform the moment, because people are otherwise occupied with “nothing doing”—ironically, in a time when there’s ostensibly more “free time” than ever, it appears impossible to get a necessary mass of people to pay attention to one thing for longer than a week. Remember Mank?

Parasite had realistic gore, but only toward the end, and unlike so many genre-conscious American films, there’s a comfort in Parasite moving between tones and modes of cinematic expression. It’s funny, politically incisive, fantastical, and at times extremely violent. The sum of these elements is a critique of modern capitalism and gig work. The gore in Bong Joon-ho’s film is justified and not overdone or lingered on. This is one way to use realistic gore. On another tip, It’s been nearly 60 years since the JFK assassination, and the American public has not had the jolt of an enormously famous person being murdered in brought daylight in particularly gruesome fashion.

We don’t want this to happen in real life. But in the movies, we need it. We need to see more heads exploding—not those of Congressional representatives, necessarily, but I know that we’re going to see a stream of Capitol and MAGA movies in the next few years, because the media and production companies are still stuck in the Trump era without realizing that nearly half their audience has already left them. That’s fine: we can work out a way for the future while they throw good money after bad. Movies can be important and “poorly made”—when people say that, they mean not realistic enough, or too realistic, in that, “I could do that.” Anybody could rig a fake bat or cat to a system of strings and send it into the face of a beautiful ambiguous European. At least it’s cheaper than “real gore.”

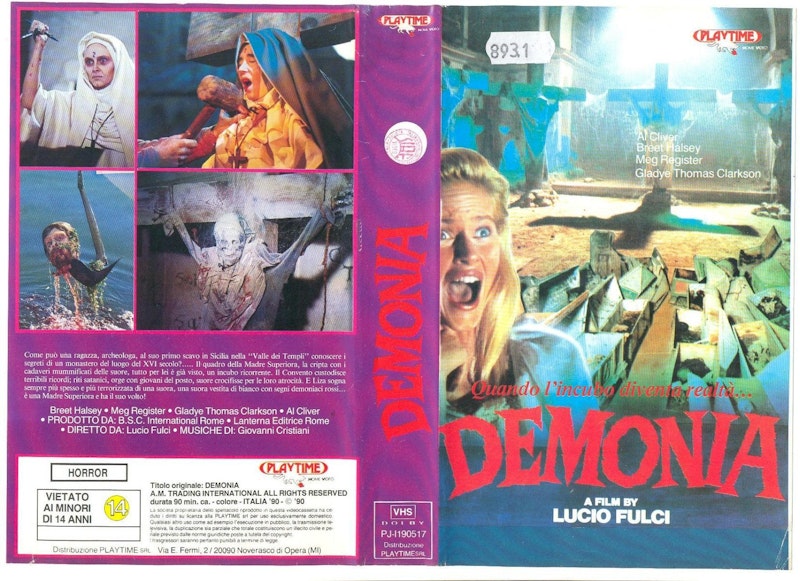

The gore in movies today is too realistic and grim to be really rewarding spiritually in any way. Just because fake blood looks realistic, doesn’t mean it should be used. Red paint blood is fine, and obvious mannequins not only standing in for their actors but dying for them, spectacularly: the “human wishbone” sequence in Demonia is beautiful, and just macabre enough without leaving one feeling bone bleached and terrified. Ari Aster makes technically sophisticated movies, but they’re cold and punishing in a way unleavened by any sense of familiarity of comfort in the presence of death.

This is what was revelatory for me about the movies of Marco Ferreri, whose “physiological cinema” is necessarily about death and decay—but he has fun. In La Grande Bouffe, four Euro stars eat themselves to death while two women watch, and it’s glorious and fun and sad in the way that light in the afternoon is sad, or when you see an old friend and consider how much has (or hasn’t) changed. This isn’t the same punishment as Aster’s work, even when he got goofy with it in Midsommar (cutting to a long shot when the first guy jumps off the cliff is pretty funny, but of course the movie still had more common with Aster’s previous film Hereditary).

The same goes for almost all contemporary “prestige” indie horror not produced on an independent basis or by Blumhouse Studios. I can only speak of two dozen or so films, but the movies Blumhouse puts out are more pungent and intent on fun more than revelation or critical adulation, but again here the gore is the problem. There’s plenty of it, but so much of it is CGI. If Blumhouse is a modern analogue to Roger Corman’s harum-scarum production style, it makes sense that these films made on a relatively cheap basis will rely on CGI when they can’t afford blood squibs.

But there’s a juicier alternative, one that satisfies both the red-blooded and the egg-headed: Fulci Wishbone. That scene, one of the last in Demonia, is the standard by which modern movie gore should be set against. Here we see a man ripped from limb to limb by two trees, pulling his legs in opposite directions as his entire inner system plops out with wet, bone-crunching sound effects and what looks like a full intestinal system. Of course this execution is committed on a dummy—the actor (already badly dubbed, as in most Fulci movies) must only suffer anxiety before his “body” is torn in two.

The death in Demonia is extreme, and more graphic and out there than anything in Midsommar, but it didn’t make me feel terrible. Horror movies shouldn’t make you feel terrible. Scared, intrigued, anxious, horny: yes. Absolutely. But I don’t need to be punished by realistic body horror unless that realistic body horror is the subject of the film. David Cronenberg explores the human body, inside and out—Aster’s films are just bludgeoning, and ultimately, deadening.

There are landmines in the past. I may be in the minority, but I find Dario Argento’s 1975 “giallo” classic Deep Red so much duller than it should be, albeit an excellent score by Goblin and a solid cast of contemporary Euro-stars… including Macha Méril, who’s killed off in the first 20 minutes and given exactly two scenes—in the second, she’s chopped up with an axe and left crashing through glass. This death, along with all of the others in Deep Red, is covered poorly and bizarrely prudish and bland. Argento’s gore was never as good as Fulci’s, but later films Tenebrae and Phenomena fulfilled this crystalline vision of spectacular death and “modern cinematography” inspired by Andrzej Żuławski’s Possession.

Those two movies are fun, whereas Deep Red (and some of Fulci’s early giallo films, like Perversion Story) is a slog, because they’re essentially police procedurals with brief flashes of violence and gore. Compared to his 1980s films, Argento looks incompetent in Deep Red next to Fulci when filming murder—whether censors got involved is irrelevant, because the entire visual structure of the film is weak. What Deep Red reminded me of most is contemporary police procedurals, so blue and hectic and dull and ugly, all loud, grim, meaning nothing.

Movies don’t have to mean anything. It’s probably better that their creators don’t intend on making anything that “means” something, other than a functional movie. But there must be a new way to explore modern anomie and 2020s nihilism without retreating into museum mourning and fodder for grief and trauma addicts. Death must be fun again in the cinema. Bring out the dancing skeletons and give them the floor.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith