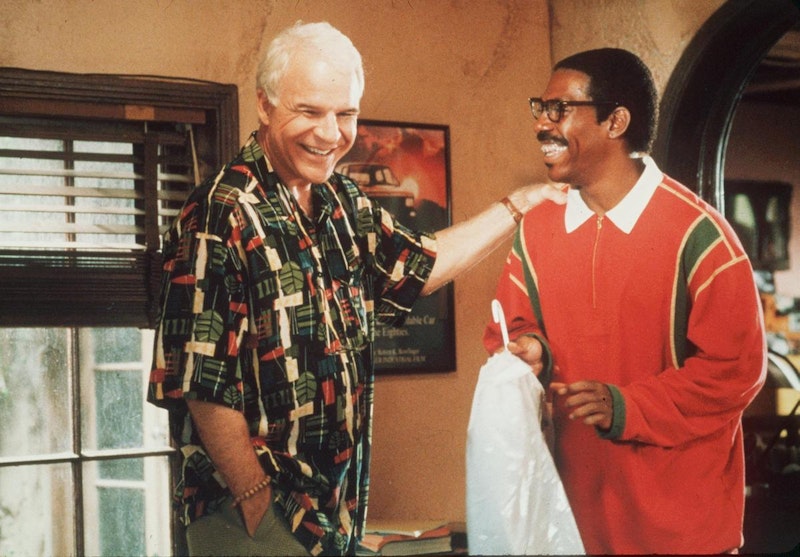

I don’t remember where I saw Bowfinger. It wasn’t one of our regular theaters, like the Regal Union Square (which I misidenitifed as an AMC in last week's column) or the AMC Village 7. It wasn’t the Angelika, Village East, or the AMC 19th St. East 6 where I saw Phone Booth and Jimmy Neutron: Boy Genius a few years later. This was 1999, and on a Downtown Summer Day, my brother, a babysitter, and I went to see Bowfinger, a new comedy starring Steve Martin and Eddie Murphy. Before I watched it for the first time in 23 years the other day, all I remembered was the highway (freeway) scene, where Murphy runs across a dozen lanes of some of the most terrifying, fast, and indifferent traffic in the history of popular cinema. What I didn’t remember was that Murphy was playing his second role here, and that the reason he’s been sent out in front of speeding cars is because he’s being recorded by a mentally-ill film crew, who have all put their faith into the craziest one of them all, Martin’s Bobby Bowfinger.

Bowfinger is a comedy about failed filmmakers: Martin’s character is introduced alone in a dusty Californian house decorated with memorabilia, props, film canisters, and junk. The arch above his front door reads “BOWFINGER INTERNATIONAL PICTURES,” and he promises his braindead followers that, “One day, that Federal Express truck is going to turn that corner and throw a couple of heavy parcels onto the porch,” and then he’ll know he’s made it. What soon becomes clear is that Bowfinger is even more of a loser than the opening credits sequence let on, and if he ever had a hit television show or even a novelty record, it’s up to our imagination. When Bowfinger accosts an executive played by a pre-rehab Robert Downey, Jr. and manages to give the guy a copy of the script he’s written for Kit Ramsey (Murphy), the guy somehow takes the script (which is called “STAR WARS” according to the cover of the script, maybe their only copy, a very funny joke that’s never ruined with a close-up).

Not that it means anything: Ramsey only ends up in Bowfinger’s movie by triangulation and stalking: their crew, including Jamie Kennedy as cinematographer and Heather Graham as a fresh-off-the-bus aspiring actress, follow Ramsey around and simply start saying their lines and allowing Ramsey to do whatever he’s going to do (at first the crew doesn’t understand why they have to stay away from their co-star, and Bowfinger tells them, “It’s an action movie! All he has to do is run away!”). They’re all deluded as Bowfinger, and only Kennedy, and eventually Graham, know that they’re fooling Ramsey, who’s conveniently in the grip of a Scientology satire called MindHead, where the various “levels” of members wear silver triangle hats, give away all their money, trust, and autonomy, and snitch on others against the organization. Terence Stamp plays the David Miscavige stand-in, staying stone faced as Murphy rants about, “White people following me talking about all this pod people shit! It’s like some secret white language I can’t decode! It’s HORRIFYING!”

I didn’t get the Scientology reference back in mid-August 1999, when I was six. Nor did I know exactly what Heather Graham was doing alone with all of those men (and one woman at the end), always bathed in golden light. But I knew she was alone with them. And I knew everyone wanted to be alone with her. And when she introduces her new girlfriend at the end as “one of the most powerful lesbians in Hollywood,” I may not have gotten the underhanded dig at Anne Heche, but I knew that some women loved other women. I may not have known the word “lesbian,” but what difference does that make? I went to a day camp run by lesbians throughout my early childhood. Things like this weren’t unusual until someone said so—and in Bowfinger, a child could see that scene straight and notice only a happy couple, not a cynical power play that tops off the running joke of Graham sleeping with everyone on the crew.

I may not have remembered much about Bowfinger except the highway scene, and a joke that went over my head at the time and only came back to me via a tag on The Howard Stern Show some years later (Martin is flirting with Graham, and she asks him, “Do you like Smashing Pumpkins?” “Are you kidding? I love doing that!”) I may not remember much else specific about that viewing or that theater, except that I think I saw Toy Story 2 there just a month before. And now I remember that this was the first theater where I ever saw “pre-show entertainment,” meaning a rotating slide of advertisements. Everywhere else started with trailers, as they should. Now I may not remember much about Bowfinger, but I know that I liked it enough then that, if I ever saw it again, I’d feel the same way. I didn’t know why, now I think I do: besides being a movie about making movies, and all of the chaos that goes into making them, this is a severe, deadpan, and often very mean comedy about a delusional artist with messianic tendencies, a small coterie of followers, a stunning lack of self-awareness, and a wildly distorted sense of his own talent.

I loved this movie.

Was I soiled, or traumatized, by seeing Heather Graham ride Steve Martin in medium close-up when I was six years old? Of course not. This isn’t pornography. Like single-gender schooling, taking a puritanical or even “modest” view on what movies a kid sees is counterproductive and shortsighted. I first heard the word “virgin” on the sitcom Grounded for Life a few years later, and I didn’t know what it meant—they wouldn’t say on primetime television. But I knew what sex was. Everyone talked about it. I don’t mean kids at school or my parents, I mean movies, television, commercials, video games, books, everything. Around 1999, my mom did have a “birds and the bees talk” with me, behind the dugout at the field where I played Little League. No one was around, and I don’t know why we were there, and I didn’t even realize that’s what she was doing until many years later.

But everything that’s talked about and showing in PG-13 American movies from the 1990s is pretty easy to understand if you’re a kid. Nobody ever says Heather Graham is “fucking” Bowfinger, or even “sleeping around”—she’s always on the arm, or in the bed, of a new crew member. The whole movie is sight gags, and besides being appropriate for children, it’s the foundation of cinema. I watched a Harold Lloyd short the other night called Bumping into Broadway (filmed in Los Angeles), and it struck me how close Lloyd and the silent era are to us, and how much time has passed since I saw Bowfinger in that small theater somewhere in Manhattan. 23 years: the entirety of D.W. Griffith’s career.

Those who insist movies will become like opera and replaced by some video game hybrid are too old to understand that I was playing video games when I saw Bowfinger in 1999 and I knew they’d never be as good, as real, as serious, or as meaningful as something that adults did—like make movies, write books, record music, and everything else that makes the world spin.

And while I don’t remember it, I know I must’ve felt just as heartbroken back then as I did earlier this week when Murphy’s second character, the one who runs across the highway and looks an awful lot like Kit Ramsey, admits that he’s actually Ramsey’s unknown and unloved brother. “You guys like me just for me, not because I’m some famous guy’s brother…” Murphy made this movie in between bigger commitments, including one of the Nutty Professor sequels, and it’s a virtuosic performance from the man who made a masterpiece of Beverly Hills Cop. Bowfinger isn’t a long movie, only 98 minutes, and Murphy’s screen time is split between the action star and the nerdy brother. But he kills in all of it, particularly when he’s complaining about never getting an Oscar (“Black man has to be a slave to win an award. White man can just play dumb. Tell you what, next movie, I’m gonna win Best Actor playing a retarded slave”).

And while I know that I loved Martin’s mean jokes as a kid just as much this time, I know I responded to the ending, and the message of the movies: these people aren’t idiots, or even insane. They may be a little bit loony, but they’re passionate and exciting and they really care about each other. Bowfinger is a very sweet movie full of slapstick, abrupt rudeness, and a picture of the way things really are in the world—brutal—that every kid should understand by that point.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith