Peter Parker, the Spectacular Spider-Man number 14, January 1978, opens in a super-villain’s lair with the human arachnid, a longstanding member of his supporting cast, and a new super-hero chained up and threatened by a time-bomb in the shape of a few sticks of dynamite rigged to an alarm clock. The danger’s standard for the genre, but this instance is archaic, hilariously low-tech even if instantly visually legible. You find the 1970s shaping the story in a number of other ways, sometimes especially striking because they’re not that obvious.

The storyline begins in issue 12, when Peter Parker and Flash Thompson encounter a cult led by two masked figures, having an assembly in Central Park. Flash recognizes one of the cult leaders as Sha Shan, a woman he’d once loved but who, four issues previously, he’d found out was now married to another man—the guy on stage with her. A fight breaks out, and Sha Shan and her husband, Achmed Korba, turn out to have super-powers.

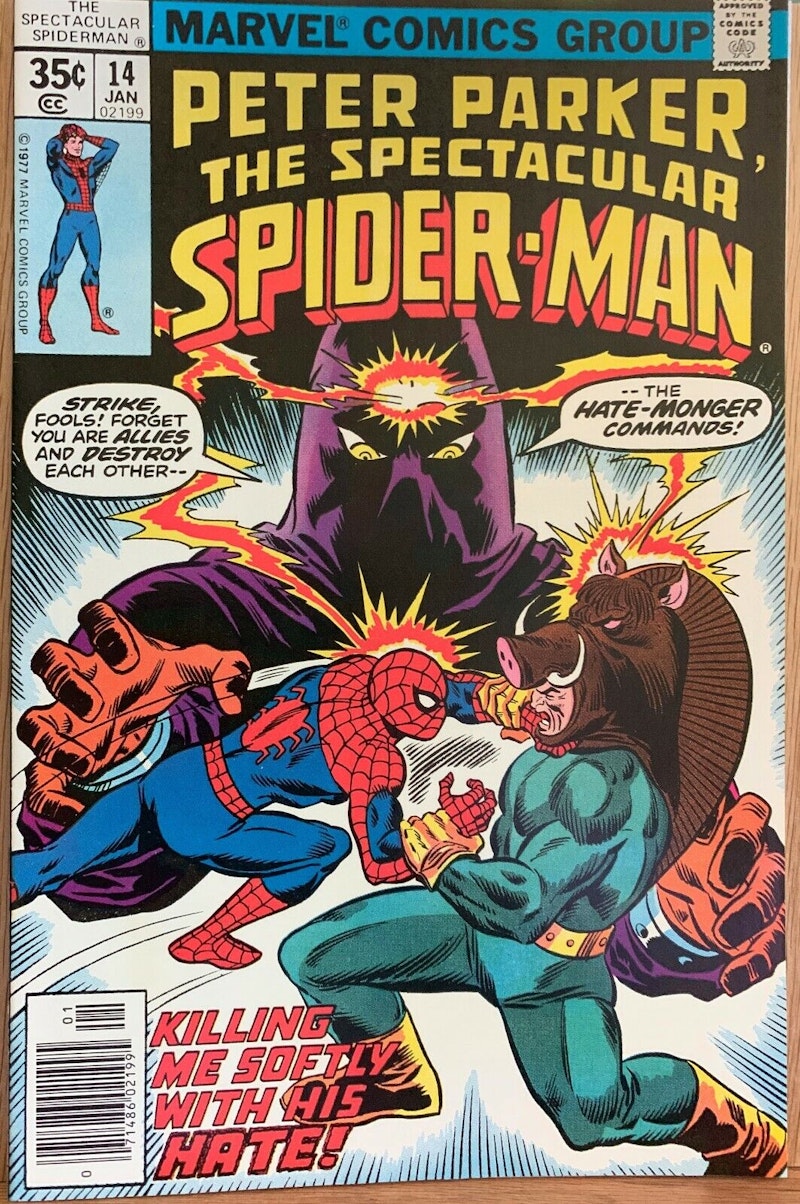

Later, Peter investigates the cult, the Legion of Light, while Flash goes to confront Sha Shan. Peter joins him as Spider-Man and is promptly blasted into a nearby alley where he runs into Razorback, aka Buford Hollis, a hayseed trucker from Arkansas who speaks in CB radio lingo. When his sister ran off with the Legion, Hollis built himself a super-hero suit, kitted out his truck with high-tech gadgets, and tracked her to New York City. He and Spider-Man fight, then team up, and with Flash in tow follow Korba to a compound north of the city. They all get captured, find out the cult’s secretly led by a villain called the Hate-Monger, and are left with the time-bomb.

Escaping, they head off to confront the cult, who’re having a major gathering at a nearby baseball stadium where the Hate-Monger will use his mind-control powers to take over the tens of thousands of attendees. A fight breaks out that lasts for the rest of issue 14 and all of 15. There are explosions, exposition, and the Hate-Monger is revealed as Adam Warlock’s old enemy the Man-Beast (that is: the super-villain here is another super-villain in disguise). In the end the good guys win, Sha Shan and Flash are reunited, and Buford’s sister decides to go on looking for something more than life in Texarkana.

All four issues were written by Bill Mantlo, with issue 12 also giving plot credit to Archie Goodwin. Pencil art in all four issues came from Sal Buscema, with Mike Esposito inking 12, 13, and part of 14; John Tartaglione also worked on 14, and Ernie Chan inked issue 15 with a nice ragged line.

As a whole, the storyline has the incoherency and breakneck pace of good super-hero comics without really being that good. The plot’s held together by more coincidence than usual, there’s no sense of the story building coherently, and Spider-Man’s pulled along by events at random. But there’s some weirdness here, with a distinct 1970s flavor.

Razorback’s CB jargon is part of it. But the Legion of Light, a cult of Asian origin that holds meetings in a baseball stadium before a crowd of thousands, reads as a comic-book reflection of the Unification Church of Sun Myung Moon, which in 1966 had inspired a researcher to coin the phrase “doomsday cult.” The conservative Moon drew attention in 1974 by having his church hold fasting and prayer vigils to support Richard Nixon. Later, in 1976, the Korean-born Moon held a series of public meetings around the US; one took place in Yankee Stadium (the PPTSSM comics climax at ‘Yonkers Coliseum’). Tell-all books by former members of the church stoked fears of brainwashing.

I remember these fears, and the pop-cultural presence of the “Moonies.” I can see the reference when I read these comics. That’s what mainstream comics did, and to some extent still do: grab stuff from the headlines and puff that material up into an action-adventure fantasy. But time passes. Some of those inspirations lose visibility to later generations. I can’t remember the last time I saw a reference to Moon or the Unification Church—unless you count links to The Washington Times, founded by Moon in 1982 and still owned by a Church-backed company.

There’s more of the 1970s in these books: Sha Shan dates back to 1972’s Amazing Spider-Man 108 and the Vietnam War. Flash Thompson met her when he was serving in the US Army; she and her father lived in a generic Orientalist-fantasy temple which was (according to Stan Lee) destroyed in the very last bombing raid of the war. Marvel forgot about her, and here she turns up years later, now largely disconnected from a conflict Marvel never really knew what to do with. It’s a very 70s mix of uneasy half-memories of the war with images of a stereotyped mysticism that help smooth the plot along.

The storyline that started at the end of the second year of Marvel’s secondary Spider-Man comic came directly from the subconscious of its moment in time. The 1970s is encoded in it in ways both obvious (Razorback’s CB slang, scrupulously footnoted and defined) and not so obvious, a four-color manifestation of a half-forgotten zeitgeist. Who remembers now the panic over the Moonie stadium rallies? But that’s what pop culture does: records, unwittingly, a record of fears and concerns—which get forgotten as society moves on. Leaving, in its wake, only comic books: time bombs of a non-explosive kind, primed to blast an unwary reader with ideas and imagery of eras long gone.