Roald Dahl had a problem. He’d signed on to write the screenplay for the adaptation of You Only Live Twice, written by Dahl’s friend Ian Fleming before Fleming’s death in 1964, after two other writers had tried and failed to adapt the novel. But Dahl found there wasn’t much to work with: he’d later compare the story to a travelogue, and observe “It was Ian Fleming’s worst book, with no plot in it which would even make a movie… I didn’t know what the hell Bond was going to do.”

He was right about the novel. It has Bond, psychologically scarred by the death of his wife in the previous book, given a mission in Japan to get himself together; slowly he does, then towards the end he finds out the villain he’s after is also the guy who killed his wife, and has a showdown with him in a coastal castle. Dahl kept Japan, and the identity of the villain, and that’s about it. The movie Bond hadn’t even been married at this point.

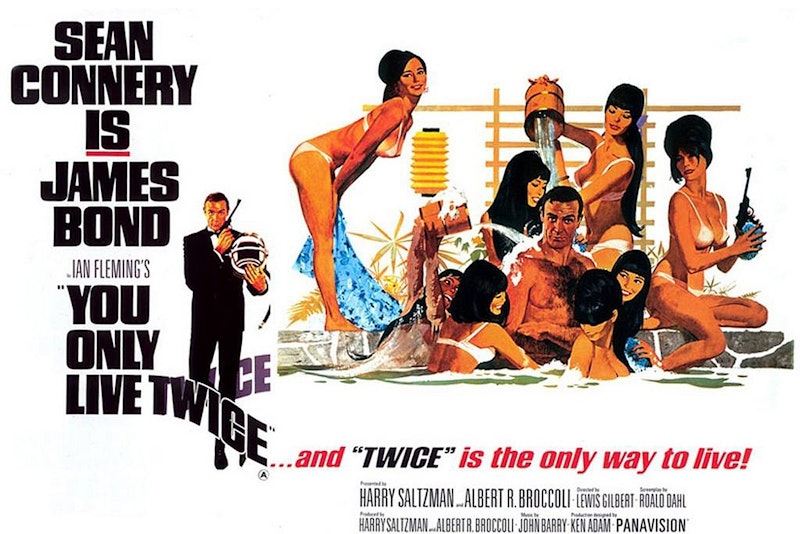

Eventually, Dahl worked out a script and the producers managed to coax Lewis Gilbert, known for dramas like Alfie, to direct it. Along with reliable editor (and second-unit director) Peter R. Hunt’s sharp sense of pace, Sean Connery returned as Bond despite dissatisfaction over his pay. And the result, despite Dahl’s desperation, works.

The plot builds well: after an introductory sequence in which Bond fakes his own death, he’s assigned to find out who launched a mystery spacecraft that space-jacked an American ship and killed two astronauts. The unknown spaceship landed somewhere in the Sea of Japan, so Bond starts looking there. He joins up with Japanese secret agent Tiger Tanaka (Tetsuro Tamba), and eventually learns the evildoer is Ernst Stavro Blofeld (a startling Donald Pleasence), leader of the evil secret society SPECTRE. A showdown in a hidden mountain base occurs.

Hanging over the action is the threat that the US will launch a nuclear attack on the USSR, believing the dirty Reds are responsible for the disappearance of the spaceship. Bond knows if he doesn’t find a solution to the mystery by a certain time, the missiles will fly, and that gives a ticking-clock urgency to the film. More than that, Dahl imagines a SPECTRE motivated by a desire for power—their plan is to set the Americans against the Soviets, and pick up whatever’s left after the superpowers destroy each other. That’s much more satisfying than the extortion scheme of Thunderball, which was right out of the Fleming book.

This is further sold by Pleasence’s performance. He’s nowhere near as physically imposing as Bond, but he’s angry, seething with rage at everyone around him, actively homicidal at all times. Blofeld’s a ball of hate you believe will blow up the world so he can take over the remains; you accept this is an international supervillain who’s built a multinational terrorist group and a hidden volcano lair.

While Pleasence only appears fully onscreen in the movie’s third act, it’s a fun trip getting there. The movie looks nice, with the typical deep-focus camerawork, and it’s interesting to see 1960s Japan—at the cutting edge of technology then as ever since, but here it’s pre-digital technology. Action scenes are well-handled, with a spectacular aerial dogfight, and it all leads to a berserk ending at a SPECTRE base that recalls the weirdness of Dr. No’s island headquarters.

It has its odd moments. Dahl made the film significantly less racist than the book, but there’s still a scene where Bond’s disguised to look Japanese for no credible reason (Connery ends up looking less Japanese than Romulan). You wonder if that bit’s an extended straight-faced practical joke perpetrated by Tiger Tanaka. The woman Bond ends up with at the end of the film never has her name mentioned, and maybe that’s because the filmmakers were a trifle embarrassed that the book named her “Kissy Suzuki.”

There’s also a scene where a helicopter picks up a car with a giant magnet. But that works, if not too smoothly, because while Thunderball represented a movement toward realism, this one welcomes the over-the-top weirdness. By this point the 1960s craze for campy technothriller spy stories (a subgenre later called spy-fi) was at its height: The Man From U.N.C.L.E., Mission: Impossible, The Prisoner. You Only Live Twice embraces that tone, with microdots and hidden X-ray machines and a ninja camp and a one-man helicopter, as well as all the stuff up in space.

Production designer Ken Adam did something a little different here, and the movie has a different tone as a result. Where previous films balanced technological madness with scenes in rich classical European settings, here we have a nonstop Japanese modernism in architecture and visual design (as well as scenes, like a fake wedding, using more traditional settings). 1960s spy films and TV shows typically worked by creating a sense of glamour against which the story happened, a world of impeccably-tailored suits and sumptuously-decorated estates. There’s that richness here, but with a distinct visual character.

And it works, because the surrealism of the film works. With this movie we begin to see a sort of self-reflectiveness in the Bond films, an awareness of their own existence. There’s a sense of Bond as myth: after all, at the start of the film he dies and comes back to life, in a thoroughly Bond-like manner.

There’s more energy in You Only Live Twice than in Thunderball, and the villain’s secret lair is well-imagined, with a sense of scale and enough extras marching around in the background, that it gives the ending a real punch. The cartooniness enhances the action. All the formulas of the Bond series so far are used with particular effectiveness in this installment, and the result’s a pure if simple pleasure.