The eighth and supposedly final Mission: Impossible movie is the fifth-highest grossing film of the year, drawing more than half a billion audience dollars and incidentally scoring positive reviews. That’s not surprising. For almost 30 years the Mission: Impossible movies have been reliable moneymakers, often picking up critical praise.

One might wonder: Why? Tom Cruise has star power, but he’s also been in his share of commercial failures. What makes these movies in particular so popular?

Going back to 1996, the first film in the series offers some hints. Paramount wanted to make a movie based on the 1966 TV series (and its 1988 reboot) for years. Once Cruise got on board as a star and producer, the project got some momentum, and Cruise hired Brian De Palma as director.

Opinions vary on De Palma’s oeuvre, but the man has an incredible command of moviemaking craft. He and Cruise wanted to make a clever, twisty film, and largely succeeded despite difficulties in putting a script together. The final movie gives credit for story to David Koepp and Steven Zaillian, with the screenplay by Koepp and Chinatown’s Robert Towne.

The first challenge was figuring out what to adapt, beyond a snazzy theme song, and how to make a film out of a concept designed as a TV series. Each episode of the show had American secret agent Jim Phelps assemble a team of experts to con a ne’er-do-well out of a MacGuffin or must-have information. The personal lives of the agents weren’t explored; the show was about the scheme and the plot, nothing more.

Solutions were found. The movie opens on a guy (an uncredited Emilio Estevez) watching a scene playing out on closed-circuit TV. He’s a part of Phelps’ crew (Phelps played in the film by Jon Voight), and he’s seeing the rest of the group work a con on an unsuspecting bad guy. The movie Mission: Impossible opens with a man watching the action of an episode of Mission: Impossible on a TV.

The information’s procured, and then there’s a cheap-looking scene, with TV dialogue and TV lighting, in which Phelps presents the crew with another mission. They set about the job, but things go wrong. Everybody except a guy named Ethan Hunt (Cruise) dies. And suddenly we’re not watching a TV show, but a big-budget movie.

Hunt’s bosses think he was a plant. Hunt escapes, but he’s a wanted man. He has to clear his name and find the real killers. And that means assembling a crew of his own. Double-crosses and set-pieces follow. If you sense De Palma’s self-conscious cleverness in the opening, you see his stylistic fetishes in the scenes that follow; split diopter shots are everywhere. And his Hitchcock obsession visible in the shape of the plot.

Hunt’s the classic Hitchcock character, an innocent man hunted by authorities who believe him guilty. Dutch angles, a frequent Hitchcock technique, emphasize pulpy danger. But the drama’s undercut by the fact that Hunt’s a spy. He’s a man on the run, but he’s used to deception and hiding out. That’s his job.

We don’t feel Hunt’s overwhelmed by his circumstances, or even see him worry about the cops. It’s a narrative tic, a nod to one of Hitchcock’s favorite story angles, without any follow-through.

There’s not really any other attempt to build up emotional stakes. We don’t learn much about Hunt, why he wanted to be a spy, why he’s acting in the service of his country or how he ended up in the Impossible Mission Force (the IMF; the TV show doesn’t predate the formation of the International Monetary Fund, but does predate the common use of its acronym).

We get a glimpse of Hunt’s mother and uncle, and there’s a nod to a backstory about the death of Hunt’s father causing money troubles. But even the obligatory romantic subplot is weirdly underplayed, which saps emotional power from a series of final betrayals. The audience gets what it needs to get to follow Hunt and be pulled into his story, nothing more. In that sense De Palma again shows his craft. You can feel the plot beats slipping into place to set up the next set-piece, like fine clockwork ticking away.

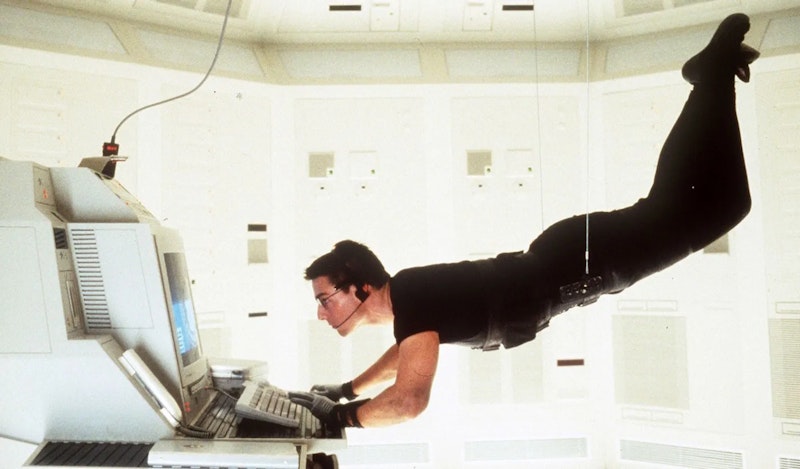

And the set-pieces, on the whole, work. If the final showdown’s weighed down by dated CGI and conventional Hollywood staging, then the bravura sequence of Hunt and his team breaking into a high-security vault in CIA headquarters makes up for it. Decorated in early Kubrick, the vault ought to strain credulity with its air duct improbably large enough for movie stars to wriggle through and positioned in just the right spot for plot convenience. But there’s a strong temptation to overlook it, as De Palma plays expertly with time and tension to make the scene memorable.

And so it goes, until an odd set of final shots. We see Hunt quit the IMF, and then, in images that echo Phelps being given the fatal mission at the start of the movie, Hunt wakes up on a plane and is given a new job. Did he not quit? Or is the whole movie a dream?

Just before we see Hunt wake up on the plane, he leaves a pub with a song playing faintly in the background: the Cranberries’ “Dreams.” A hint from De Palma? Or a lucky coincidence in a script went through too many drafts? Either way, it gets at what the film gives you at its best: a fun dream of an old TV show, upgraded to a blockbuster movie by a director with a playful cleverness and craft to burn.