James Bond’s been strapped to a solid slab of wood by the evil Auric Goldfinger, and the beam of an industrial laser’s inching its way up the slab toward his groin. “Do you expect me to talk?” he snaps.

“No, Mister Bond,” Goldfinger chortles, climbing a nearby flight of stairs. “I expect you to die!”

It’s one of the most famous moments in the James Bond films, part of the first scene filmed on 1964’s Goldfinger, the third movie of the series. It’s based off a similar scene in Ian Fleming’s book, which is less engaging; instead of a laser the book has a sawblade, and Goldfinger does expect him to talk. Here as elsewhere, the Bond films improve on the novels by making them wilder and less realistic.

Goldfinger was directed by Guy Hamilton, coincidentally a friend of Fleming’s, and was written by Richard Maibaum and Paul Dehn. As was becoming standard for the Bond films, the plot stuck close to the novel but added gloss and visual excitement: James Bond’s assigned first to observe and then stop suspected gold smuggler Auric Goldfinger (Gert Fröbe, dubbed by Michael Collins). Captured by Goldfinger, Bond learns that Goldfinger plans to set off a nuclear bomb in Fort Knox to manipulate the price of gold. His only hope is to seduce Goldfinger’s private pilot, Miss Pussy Galore (Honor Blackman).

This doesn’t sound like much, but the movie lives in its visuals. It’s not especially well-photographed—it’s a little dingier than the first two movies, and the compositions unexciting. But the story’s told clearly and effectively. Production designer Ken Adam returned from Dr. No, and his sets are spectacular, particularly Goldfinger’s base and the vault at Fort Knox where Bond has a knock-down fistfight with Goldfinger’s ominous lieutenant, Oddjob (Harold Sakata). And editor Peter R. Hunt keeps things racing along that you hardly notice how rickety the story is.

Bond’s ordered at the start of the film to observe Goldfinger; for no real reason he proceeds to meddle in a card-cheating operation Goldfinger’s running. Bond’s main action in the film is seducing Pussy Galore, who’s the one to foil Goldfinger’s scheme off-camera. When Bond spies on Goldfinger’s compound in Europe, Goldfinger captures him and prepares to kill him with the laser before Bond bluffs him into thinking Bond knows something about his plan—so Goldfinger then flies Bond across the Atlantic with him to his American headquarters before interrogating him.

And then that headquarters becomes the site for a meeting Goldfinger has with the heads of American crime syndicates, where Goldfinger explains his plan using an elaborate model and sliding floors and the best bleeding-edge technology 1964 had to offer. Then he kills the heads of the syndicates. For no reason.

But it also doesn’t make sense that Bond, a spy, is given the job of taking down a gold smuggler. The movie works because it creates a dreamlike logic of things happening because they must. That scene with Goldfinger’s exposition—it’s narratively pointless, but it’s lovely to watch, not least because Bond escapes captivity long enough to stumble into the backstage area of the giant interactive model Goldfinger’s made of Fort Knox. We see the undercarriage of the mechanisms, the steel-and-oil analog solidity of 1960s technology, and it’s still impressive.

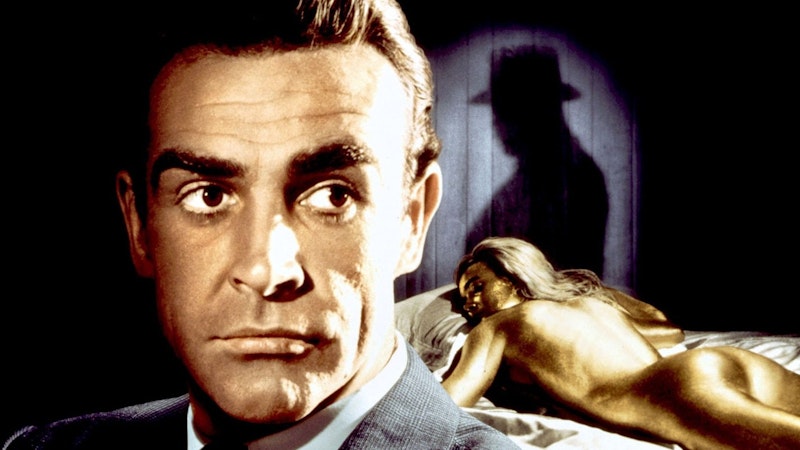

More images: the movie opens with Bond swimming into a harbor in a frogman’s wetsuit before stripping out of it to reveal an immaculate tuxedo underneath; it feels like the distillation of Bondness. Or consider the bomb at the end, a weird concoction of wires and spinning disks and blinking lights. In between there’s Pussy Galore’s Flying Circus, a team of black-clad blonde pilots and the second-best-known Flying Circus in British film history. There’s also one of the most famous images of all the Bond movies: a woman killed by being painted gold. It makes no medical sense. It works anyway.

And then there’s the car. Bond’s given an Aston Martin tricked out with gadgets to use in tailing Goldfinger. Most of those gadgets are seen in a major set-piece toward the center of the film, as Bond tries to get away from Goldfinger’s men. The girl with him at the time has a moment in the middle of the chase, a smile of pure joy at all the wonderful toys; and that’s the point of the movie, that’s what it's aiming for, the euphoria and dizziness of high adventure and high-tech wonder.

It’s played just right. Connery’s had two films to work out his approach to Bond. Blackman’s had two seasons of playing the lead on surreal spy TV show The Avengers; both of them know how to tell the kind of story that doesn’t live in traditional character arcs. And Harold Sakata tells us all we need to know about Oddjob without a line of dialogue through presence and movement alone.

We get glimpses of Bond’s character in the way he interacts with his superiors at MI6: an obnoxious schoolboy, so self-assured his masters want to swat him down, so clever they can’t find a way to do it without looking like idiots. It’s a nice variation on Bond the cool man of action. Less engaging is his arrogance, particularly toward women: Bond the ass-slapper. His confidence in his own infallibility gets two women killed; his only real contribution to the plot is to bring another woman over to the good side by sleeping with her.

The film’s in the tradition of boy’s-own stories, in this case for slightly grown-up boys. It should, objectively, be a bad movie. The plot’s incoherent, characters rudimentary, the dramatic arc’s flat. But it hangs together, and is one of the best films of James Bond’s 60-year-plus career.