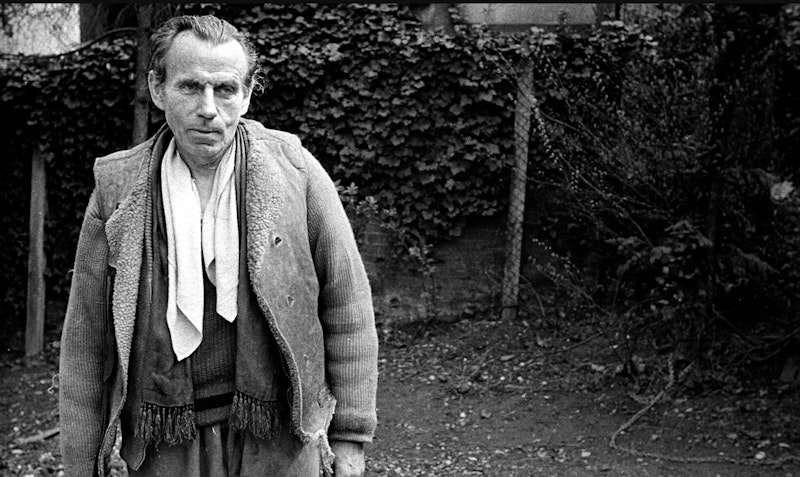

Having finally gotten around to reading Louis-Ferdinand Céline's celebrated novel, Journey to the End of the Night, I'm again reminded of what a rotten human being the French author was. Céline was a vocal anti-Semite who fled France in 1944 for Germany after being accused of collaboration with the Nazis. Only after receiving a pardon in 1951 was he able to return. France graces artists with the sort of artistic license that allows for a separation of their work from their character; talent trumps morality. It's hardly a surprise that persecuted author Oscar Wilde chose Paris as his haven in exile at the end of his life, after his release from prison. And Wilde summed up succinctly the French approach to art: "There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all."

The Irish libertine was echoing that French philosophical slogan, "l'art pour l'art"—"art for art's sake—that 19th-century French poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire, who was once prosecuted for obscenity, embraced in his time. In Baudelaire's essay on Edgar Allan Poe, who he introduced to France via his extensive translations of Poe's work, he denounced didacticism in art and the notion that art should serve a useful purpose. While Baudelaire admired Victor Hugo's imagination, he had no use for the French novelist's morality lessons.

Known as the "father of modern poetry," Baudelaire had a philosophical opposition to, in the name of "progress," any idea that would diminish the importance of artistic beauty in service of making art into a vehicle for social and moral change. Compare this view of art with the modern left-wing sensibility of attacking any art (sometimes physically) that may be perceived as offensive to their allies, which is essentially an extension of the Soviet Union's "Socialist Realism" philosophy, under which artists were expected to use their work to advance the principles of a classless society. That era produced no enduring artistic achievements, it's a recipe for mediocrity.

Compared to Americans, the French never required much morality or adherence to progressive societal norms from their artists. Michel Houellebecq, France's most renowned author for several decades now, when asked if he was an Islamophobe, answered, "Probably yes." He's also said that Islam is "the stupidest religion." Bound by the loose restraints of French literary culture, the author feels no need for self-censorship as an American writer would. He felt free to write Submission, a novel about Islam bending the French elite to its will as it seizes power. Given the lack of separation between Islam and government in Muslim nations, this is an important concept for artists to explore, but an American author would risk cancellation in doing so.

French artists having carte blanche to deal frankly with taboo topics is a sign of France's cultural maturity. In comparison, the U.S. has often come off as childlike and moralizing. Henry Miller's Tropic of Cancer was published in Paris in 1934 (Baudelaire already had equally salacious material published there decades ago by this time) after it was banned in America for graphic sexual content. The same story repeated itself with Joyce's Ulysses, Nabokov's Lolita and Burroughs' Naked Lunch. In France, adults aren’t considered children who need a "big brother" government to protect them from subject matter that would presumably corrupt them.

When Grove Press published the banned novel in the U.S. in 1961, 60 obscenity lawsuits were brought against booksellers that sold it. Pennsylvania Supreme Court Justice Michael Musmanno wrote, sounding very American, that the book "is a cesspool, an open sewer, a pit of putrefaction, a slimy gathering of all that is rotten in the debris of human depravity." Baudelaire was also accused of celebrating depravity, but there was a passionate philosophical commitment behind his choice of criminals, prostitutes, and other riff raff as his subject matter, rather than a desire to celebrate them. The poet was committed to the idea that art must struggle to create beauty from even the most depraved or “non-poetic” situations, a notion that, while it didn't sit well with traditionalists, set him on the path as an artistic pioneer.

Céline was also an artistic pioneer, and one of the greatest writers France has produced. He did for the French language what James Joyce did for the English language, and while it's despicable that he wrote some bigoted rants against Jews right around the time they were being herded into gas chambers, that garbage didn't change the impact he had on the literary world. Baudelaire influenced French poet Arthur Rimbaud, and Rimbaud influenced Céline, who went on to influence Samuel Beckett, Henry Miller and Charles Bukowski.

Céline was a critical link in a chain that produced great literature, which in the end is the overriding factor for the French. But this doesn’t imply that celebration of his work isn't controversial in France. The French government publishes annually the Recueil des Célébrations, a list of cultural events and personalities to be commemorated over the next year. After the storm of disapproval that followed Céline's name being included in 2011, culture minister Frédéric Mitterrand removed it. But the intelligentsia revolted. There were accusations that the "Jewish lobby" had cowed the French government into submission. Literary giant Philippe Sollers accused the Culture Ministry of "censorship." Frédéric Vitoux, who wrote a biography of Céline, compared the move to the USSR's airbrushing of history under Stalin. Celebrity intellectual Bernard-Henri Lévy stated that there'd been a missed opportunity to try to understand how a "truly great author" can also be an "absolute bastard."

Years before this incident, it was established that art in France transcended morals, politics, and "proper" behavior, so the intellectual outrage that ensued wasn’t a shock. France proved that it’s the haven for the world's artists who find their voices are under attack from opportunistic politicians, moral scolds, and strident do-gooders.