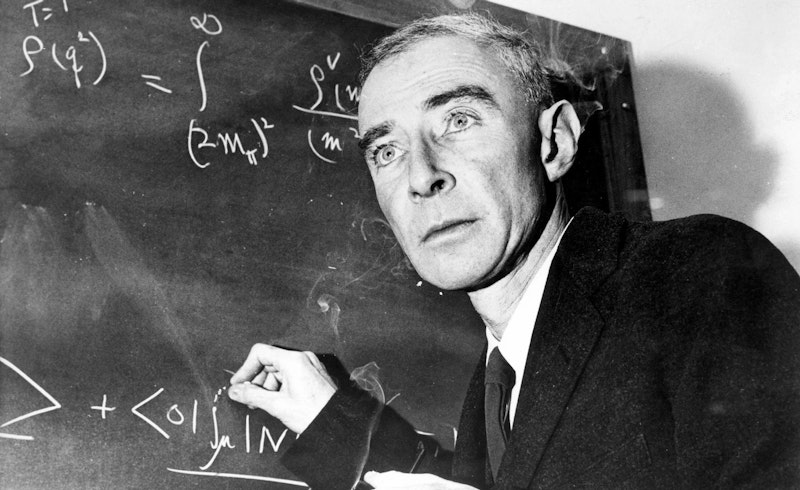

I finally got around to watching Oppenheimer, which mentioned that J. Robert Oppenheimer theorized about black holes before he led the Manhattan Project. Theoretically I knew this, but I’d forgotten. I looked up an essay about Oppenheimer I’d once read, by physicist Freeman Dyson, who considered the former’s 1939 paper introducing the concept of black holes, “On Continued Gravitational Contraction,” “Oppenheimer’s one and only revolutionary contribution to science,” and several times asked his friend why he didn’t return to that research, never getting an answer.

Oppenheimer had a negative view of a 1960s play that showed him lamenting his role in creating the atomic bomb, and likely would’ve disliked the 2023 film for the same reason. He died, however, with regret at not having done more in pure science. The somber last paragraph of Dyson’s essay states:

“Late in Oppenheimer’s life, when he was sick and depressed, his wife Kitty came to me with a cry for help. She implored me to collaborate with Robert in a piece of technical scientific work. She said Robert was desperate because he was no longer doing science, and he needed a collaborator to get him started. I agreed with Kitty’s diagnosis, but I had to tell her that it was too late. I told her that I would like to sit quietly with Robert and hold his hand. His days as a scientist were over. It was too late to cure his anguish with equations.”

I found that off-putting when I first read it, as if Dyson were dismissive of someone no longer in his league in physics. Re-reading, I recognize the compassionate intent, though I wonder whether it wouldn’t have been worth trying to engage the aging physicist with some equations. In any case, Dyson had his own unfulfilled ambitions, such as that a ban on nuclear explosions in space ended Project Orion, which would’ve built a gigantic spacecraft propelled by hydrogen-bomb detonations. Both men started out in pure science (Dyson contributing to quantum electrodynamics) before gaining greater notice elsewhere, in Dyson’s case as a writer as well as tech visionary. Still, when the younger physicist applied for a leave from the Institute for Advanced Studies in 1958 to work on Orion, such a diversion into applied science was approved only reluctantly by the institute’s director, Oppenheimer.

Oppenheimer died in 1967, a year marked by a resurgence of interest in the gravitational objects he’d conjectured; the term “black hole” was promoted by physicist John A. Wheeler at a conference that year, in response to a suggestion shouted from the audience. Dyson lived until 2020, seeing the beginning of an era in which telescopes would capture images of black holes (more precisely, images of matter circulating at black holes’ event horizons). Dyson’s tech visions evoke possibilities for future or alien civilizations such as a Dyson sphere, a megastructure that would capture the energy emitted by a star. Some scientists imagine such a sphere built around a black hole, drawing enormous energy from gravity.

Gravitational waves, emitted by black holes and other powerful celestial phenomena, such as neutron stars and supernovae, are a burgeoning area of pure science. Such ripples in space-time have been detected by the Laser Interferometry Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), which uses facilities in Washington state and Louisiana. Early this year, funding was approved for the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), a collaboration of the European Space Agency and NASA; this will involve three space probes, launched in the 2030s, that’ll form a triangle in solar orbit, detecting gravitational waves from enormous black holes in other galaxies and picking up echoes from the primordial universe.

—Follow Kenneth Silber on Threads: @kennethsilber