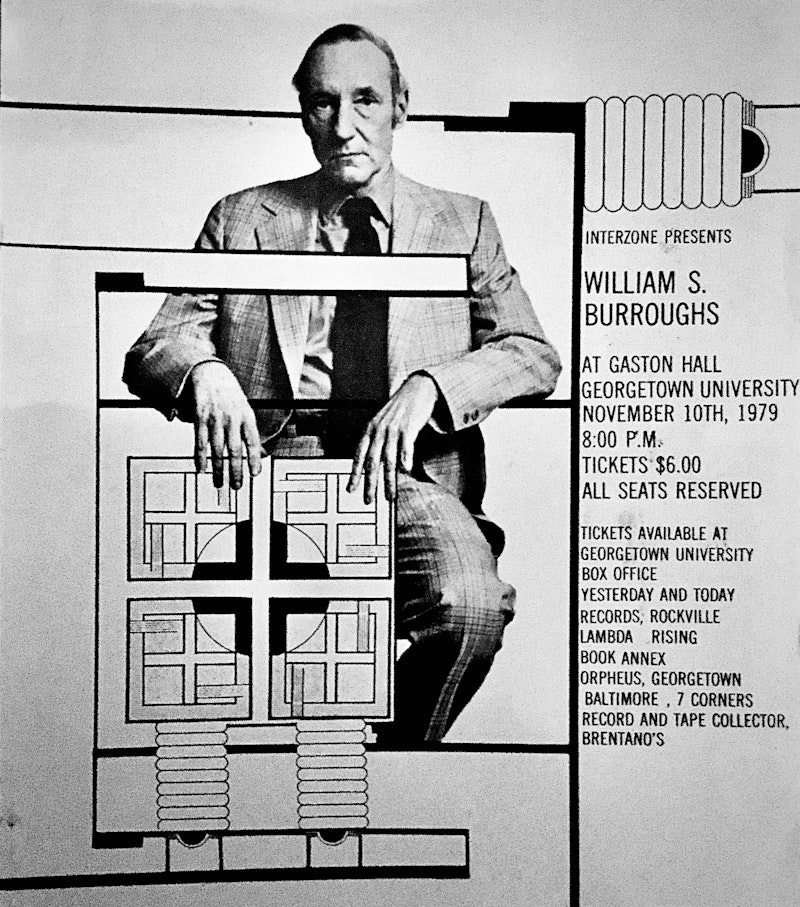

Ten feet tall—looking down on us, talking backwards—the man would’ve been 107 years old on February 5th. The same tall, thin man carried a black briefcase across Georgetown University’s Gaston Hall’s sparse stage back on November 10, 1979 at 8:35 p.m. He sat down showing no emotional reaction to a Washington DC’s audience applause.

Imagine a CIA agent testifying before Congress running a bit late. He opens the briefcase. A few papers are placed in order. The man adjusts his glasses and the desk microphone. He took a deep breath and cleared his throat. William S. Burroughs was ready to speak.

Earlier that evening outside Gaston Hall, John Waters was there along with others from Baltimore including City Paper writers Pam Purdy and William F. Ryan. Poets Joe Cardarelli, Andrei Codrescu and David Franks talked in the hallway. A coming-of-age generation of art students attended too. Everyone sought the same—a much-needed kick in the ass from a Beat Generation god.

The poetry trio kept a close watch on the Baltimore Kid. Tom DiVenti was busy spinning chaos after a fifth of vodka and tequila. The Interzone staff handled the commotion with discretion.

That kind of misbehavior just added to the erratic, unreal nature of a Burroughs reading. His public appearances were rare events with even fewer book signings. Let’s consider some notes, research shows: Burroughs’ novel Cities of the Red Night was yet be published, reading tickets were six dollars and the event was short, under an hour. During the winter of 1978, an eclectic three-day affair linked to Burroughs took place in New York City, the legendary Nova Convention. That evening Burroughs proceeded to feel the love and expressed himself in calm, deadpan manner. He targeted a number of specific topics in a non-derisive manner.

Using an unfettered reality filter, he wreaked verbal havoc. His subject matter included: a purple-ass baboon runs for president, the usage of Naked Lunch’s Doctor Benway’s persona, “Now, boys, you won’t see this operation performed very often and there’s a reason for that…” and deliver shocking queer prose steeped with a disdain for authority.

Reading Burroughs rewired my brain and he was way ahead of his time. In light of today, Burroughs knew viruses could control the world. When he wrote about contagions in 1964’s Nova Express, he gave them names: Limestone Johnny, Hamburger Mary and Blue Dinosaur. Burroughs’ writing, books and recordings continue to resonate like a taste of straight strychnine.

As John Waters’ guest, I was lucky and grateful to attend a reading reception afterwards in a tony DC neighborhood outside Georgetown. It was the first time I met Burroughs. What a night. I wasn’t star struck in any fashion; the encounter was inspiring. Why not? It was Burroughs. Thank god I didn’t fall all over the place. Our striking conversation was brief. We’d have a few more encounters.

About a year later in New York City I went to a party at a “bathtub in the kitchen” tenement flat on the Lower East Side. Burroughs resided nearby at 222 Bowery at the time. It was “The Bunker” days when Burroughs lived in a former gym locker room with its curved corners and windowless white-walled rooms.

That evening many engaging East Village artists stuffed themselves into the bohemian walk-up apartment. Burroughs was there. As a rite of passage for the ceremonial event, we smoked a joint together. I asked about the Nova Police and he said, “If these criminals vanish, the police must create more in order to justify their own survival.” His reply was delivered while sitting on the edge of the bathtub.

It was mesmerizing to watch his lips move around a chiseled skull pulled tight by sallow skin—tingled by his voice in AMSR quality. Burroughs’ eyes were intense, emitting a warmth with piercing gaze—a Superman’s laser eyes with an ability to see right through you.

A catchy soundtrack played on a nearby Boombox, “96 Tears” by ? and the Mysterians repeated itself over and over. A piece of artwork highlighted the setting: a table top diorama of butchery, an homage dedicated to the Jonestown Massacre composed of melted, green plastic soldiers splattered with red paint.

Fast forward to 1991, my friend Don Gilbert, who worked with me at New York Press, asked if I’d heard about an upcoming Burroughs signing. I said, “No, really, when?” Burroughs’ book version of The Seven Deadly Sins was slated for a signing at an Astor Place bookstore. The limited edition had a 12-gauge shotgun painting on balsa wood tipped on the cover as artwork.

Don and I shared celebratory substances on occasion that gave us additional reason to go. Outside the bookstore that cold, misty November afternoon people were lined-up around the block to get in. Believe me, nothing was too cool for this crowd. While standing outside, there was a moment when everyone’s head turned around in unison. Burroughs was spotted approaching west on Astor Place. The distinguished gentleman now walked with a cane. He swaggered up to the entrance wearing a long, black leather trench coat. Don and I nodded with approval.

We waited for several hours and finally got in. Then one of the youngest of the Beat poet writers arrived—Gregory Corso acting full-on outrageous, hollered and shouted for Burroughs’ attention. Sound familiar, it made sense. After all the excitement, I caught a cold. This would be the last time I saw Burroughs.

Now, Burroughs and Don are both gone. I never had a taste for junk, well aware of its allure and danger. When I finally arrived at the signing altar that day, I couldn’t help but notice how Burroughs had aged. Ready for my communion, I asked him with a whisper of recognition, “How are you?”

Burroughs looked up directly into my eyes and replied with a warm welcome. In a matter of fact manner he said, “Ah yes, Washington DC, how are you?” I smiled back at Bill.