It was unseasonably warm on Wednesday, and before the cicadas erupt, masses of people were eager to run outside and drink overpriced beer in the middle of a blocked-off street, stare at their friends and take pictures of obscured objects or indications of outdoor activity: a book, a coffee, a muffin, a menu. America has begun to “resume the pose,” however absurd and uncertain everything remains.

So businesses in Baltimore are allowed to operate once more, taking customers alternately meek and irate, criticized for doing what they can in an impossible situation: opening up at all before the pandemic is over. Shuttering for a year or two isn’t a problem for certain adjacent establishments, but The Charles Theater reopens today. It’s showing Minari, French Exit, The Father, and Godzilla vs. Kong. First run blockbuster aside, typical fare, “back to normal.” The Senator remains closed, the CinéBistro in Hampden is closed for good, and the Landmark at Harbor East was taken over by new management and will reopen after renovations.

Encouraging, but one can only be so optimistic: “In Harbor East, the operator plans to schedule screenings of new releases as well as independent and art house films, according to the announcement.” This, from the landlord, is more discouraging: “The eventual repositioning of this asset allows us to more strategically tailor the entertainment experience to our guests’ needs, as well as the safety protocols which the current circumstances demand.” Nothing new, there are bloodsuckers everywhere, but with people like this managing “cinema” worldwide, you can only feel so secure in their promise to deliver and maintain a “true entertainment hub for the district and more broadly, the city of Baltimore.”

This story is playing out throughout the world now, as conglomerates plop what my friend John Jones called “chipotle dorm jails” everywhere. Some of these include movie theaters. They’re new but already look old, outmoded, really just profoundly ugly. Towson’s Cinemark, open for some months with limited capacity, fits the description, as did the CinéBistro in the renovated Rotunda complex, another disaster of design. But this too, is nothing new.

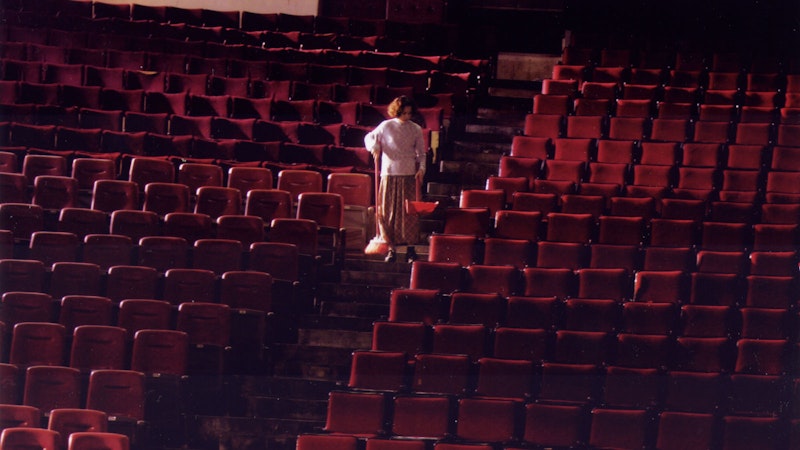

Nick Pinkerton writes about this trend in his excellent new book Goodbye, Dragon Inn, focusing on Tsai Ming-liang’s 2003 film of the same name. He describes “the curious double nature of moviegoing, both a communal and deeply private, solitary activity” that vanished in the last year, and was fading for some years before that. Nothing new: Tsai’s film was only prescient if you didn’t assume that digital technology would quickly reach a point of supremacy over celluloid as production and distribution materials.

As Pinkerton notes, the DCP changeover in the early-2010s made it easier and cheaper for movie theaters to operate, even with reduced capacity. The ghosts of Tsai’s film still have time to linger, and I watched as audience members drained from seats throughout the last decade—at a certain point, people only turned out for event films. In 2019, there were many (Midsommar, Joker, Parasite, Us—to name just a few with single word titles). But in the five previous years, the “regular moviegoer” was left hanging more often than not. One of Pinkerton’s most astute observations is that the festival success of Hong Sang-soo is “significant” not because of his films (as good as some of them are), but that they’re deliberately “no budget” and often sloppy: “We are a long ways from the ambitious undertakings of an Antonioni, a Truffaut, or even Yang or Tsai.”

Goodbye, Dragon Inn is one of the most powerful and immense films made in the new millennium, and I recommend watching King Hu’s Dragon Inn immediately before Tsai’s film. Hu’s wuxia classic echoes through the nearly empty Fu-Ho, a second run theater in Taipei once bustling (as shown in a brief prologue), now a rundown spot for men to cruise. It’s closing, and this is the last movie that’ll ever show in the Fu-Ho. We watch a Japanese tourist awkwardly make his way through the patrons, sizing them up and regularly rebuffed. The first line of dialogue—“Did you know this theater is haunted?”—occurs 40 minutes into an 82-minute film.

There isn’t much more. No matter, if you love moviegoing: Chen Shiang-chyi plays the disabled ticket taker, who wanders behind the screen during a climactic sword fight prominently featuring Ying Bai—it’s here, in this otherwise formally strict piece of “slow cinema,” that entertainer and spectator, idol and worshipper, superhuman and mere mortal, meet in a series of rapid intercuts between the two. It’s an enormously powerful cinematic expression of the kind of transcendence and communion that can happens at “the movies”—because they are still that, “the movies,” a place, a territory.

2020 confirmed that movies only exist at a level beyond niche subculture if the cinema remains a territory. Pinkerton, on Tsai’s attempts at a new cinema funded and exhibited by museums and galleries, correctly praises one of cinema’s prime virtues: “Despite the myriad compromises built into the systems through which films are financed and exhibited, the traditional dependence on rapport with a popular audience has kept cinema free of the perfectly insidious financial arrangements that define the gallery world, which depends in no small part on catering to the whims of a handful of obscenely wealthy international collectors.”

One problem: how much contact can people have with these new, “modern” renovations and protections, as with the Harbor East Theater? I imagine it’ll be impossible to cruise or cry as the few patrons of the Fu-Ho theater in Tsai’s film do. The theater in Baltimore that most resembles that of the Fu-Ho is The Parkway, whose upper balcony could play in a pinch for a key scene in Tsai’s What Time Is It There? That space, opened in the 1910s, belongs to the same category as the shuttering Fu-Ho, or the Senator Theater. These are “secular temples,” a phrase not unique to Tsai, Pinkerton, or me.

I’m not sure what “modern-safe” theaters will look like, but I know that they’ll be “the movies,” and that an art gallery will never be the territory of “the cinema,” and that they’ll never be “the movies.”

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith