I first came across The Dark Gods sometime in the late-1990s. I was living in Glastonbury at the time, working on my second book. I went round to someone’s house and he told me that he’d illustrated a book once. His name was Tom Eveson, and the book was The Dark Gods. This struck me quite forcibly at the time as Glastonbury is all “love and light” and people wafting around in floaty dresses being “spiritual” all over the place. The very title of the book seemed to contradict all that.

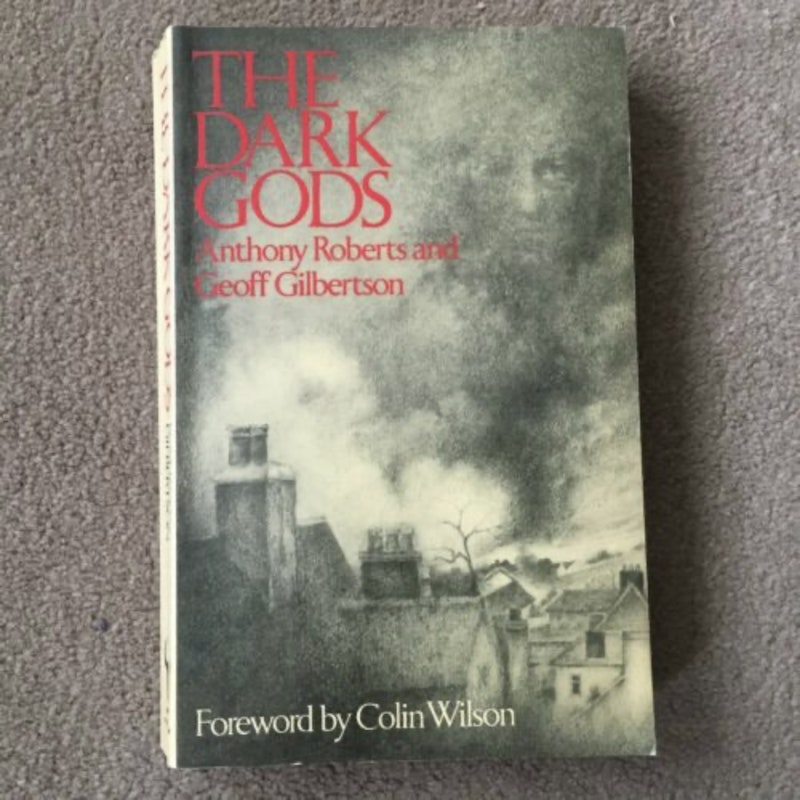

Eveson’s drawing is on the cover. It’s in pencil and shows an image of Glastonbury, or some other town, from high up over the rooftops. There’s a faintly discernible face in the clouds on the right hand side. There’re a couple more of his pictures inside: one of H.P. Lovecraft, and another of some of the other figures who make an appearance in the book, including Madam Blavatsky, Rudolph Steiner, Adam Weishaupt, Aleister Crowley, Houston Stewart Chamberlain and Dietrich Eckhart. I was impressed by Eveson’s art.

Sometime later I met one of the authors, Geoff Gilbertson. I was working on my fourth book and visiting a friend in Muswell Hill. Either Gilbertson was staying there as well, or he lived nearby. We all went to the pub and had a jolly time. I remember no more about that occasion. After that I was surprised to see a copy of the book on a friend’s shelf. This was around 2007. My friend’s a computer scientist and it seemed an odd book for him to have. He explained that he was interested in comparative religion and the book covered some aspects of that subject. He didn’t think it was a very good book.

It was some time after this that Gilbertson contacted me. Later we began to exchange emails. I asked what he was up to these days and he said he designed websites. I was thinking of upgrading my website at the time and asked if he could do this for me. He said he couldn’t as he was ill, but passed me on to a friend of his who he described as his “apprentice.”

After that I got a phone call. There was no name attached to the number so I didn’t know who it was. I answered and an eerie voice came out of the ear piece. It’s hard to describe. Very high-pitched, like the twittering of a strange bird, or the sort of sing-song voice you might put on to depict an otherworldly creature from a mystery play, like and elf or a fairy. It was so odd I couldn’t make out what the person was saying at first. I thought it was some mad woman haranguing me. It took a minute or two for me to realize that this was Gilbertson. I was sure he didn’t sound like this when we went out to the pub all those years ago. We arranged to meet at a friend’s house in Soho.

This was the woman he had described as his apprentice. We were going talk about my website. I rang the bell to the apartment and was buzzed in. Gilbertson was standing on the top of the stairs waiting for me, twittering in his otherworldly way. He was very excited, flapping his arms about like a bird, dancing from one foot to the other. He had a bald head and many teeth missing. His legs were wrapped in bandages. He didn’t stay long. Despite the fact that I’d travelled up from Kent, he was gone within 10 minutes of my arrival. He just upped and walked out the door without saying goodbye.

“He’s always like that,” said Bianca, the website designer.

I said, “What's with the voice?”

She said that he’d had a psychotic breakdown and this is what had become of him. Either that or it was the medication, she told me.

I met him a few more times after that, always in London. Once Bianca and I went to see him at his home. It was a small apartment in a large municipal building which he was sharing with other people with mental health difficulties. There were nurses on call. He showed us his private space. It consisted of one chair in front of a TV with discarded microwave packets all over the floor, with another room where his bed was harbored. There was nowhere to sit down. I suggested he might get some more furniture so he could have visitors, but he gave me a strange, sidelong look. It was obvious he didn’t really enjoy people’s company all that much.

We walked around the part of London where he lived. Everyone knew who he was. How could you miss him? He had the strangest walk. He waddled along like a wooden marionette, with his arms flat by his side, his hands turned out at right angles, palms down. He grinned a lot, a great, wide child-like grin of wonder, as if everything was perfectly delightful, but I knew he wasn’t really happy. He once told me that the last time he remembered being happy was in the pub that night when we’d first met.

Other than that he used to ring me up, several times a week. The conversations were always brief and often bizarre. I didn’t always answer the calls.

Then he announced he had cancer. This was in Bianca’s apartment. He said, “I’ve got cancer but it’s okay because I’ve got good friends.” He was supposed to be going into hospital for an operation, but then surprised us by declining the treatment. He said, “Well, I’ve got to go sometime!”

He died on October 24th, 2017. The cause of death was “malignant neoplasm of the sigmoid colon and ulcerative colitis.” I wrote an obituary for him, which was published in the Guardian, and another, longer piece which I published on my own website. I spoke to a number of his friends to get the information for that, some of whom later became my friends.

According to almost everyone I spoke to, he blamed his breakdown on the writing of The Dark Gods. First published in 1980 by Rider/Hutchinson & Co, it has a foreword by Colin Wilson. It went through at least two editions. There’s the earlier version with Eveson’s picture on the front, and another version, published by Panther Books in 1985, with a picture of a vampire-like female creature with lightning flashing from one eye. Copies of both editions sell for absurd amounts on the internet, particularly the earlier edition. It probably has more to do with the foreword by a relatively well-known author, than the book itself.

Gilbertson and I did a book swap at one point. I gave him a copy of The Trials of Arthur, my fourth book, and he gave me a copy of The Dark Gods. I tried to read it at the time, but it’s style is hard to get into, turgid and old-fashioned, with a lot of adjectival woo-woo, particularly from Anthony Roberts. It’s been sitting on my shelf ever since.

I decided to read it this week, I’m not sure why. It’s an ultimate conspiracy theory book, preceding Dan Brown and David Icke by more than a decade. Its basic contention is that there’s a malignant force in the Universe, undermining humanity at every turn, which the authors have attempted to delineate using a variety of sources: from myth, fiction, folk stories and history. It mixes up its sources shamelessly, treating the fiction of H.P. Lovecraft on a par with accounts of UFO sightings and the writings of Madam Blavatsky. The book admits that much of Blavatsky’s work was plagiarised, but nevertheless decides to take her seriously. Likewise Lovecraft, whose fictional output is read as if it’s describing real phenomena, and Wolfram von Eschenbach, whose medieval romance, Parzival, is used thematically throughout the book. Gilbertson takes delight in putting phrases from his disparate sources into italics to show some kind of link. If the description of a malign character in one book matches the description of a character in another book—if they have dark skin, or oriental eyes, or their eyes shine in the dark—then this is taken as proof that both are representatives of the Dark Gods the book is attempting to bring to our attention.

You can read a review of the book here, and see a video review here. There are also reviews on the Amazon page and on Goodreads. The Goodreads review page is particularly poignant as it includes an entry by Gilbertson himself.

Here is what he wrote:

I am the co-writer of "The Dark Gods." I became a web designer after I became an author.

I'm not sure now I believe everything I wrote. I am glad we got five stars.

I now live in London.

That’s typical of Gilbertson’s later terse style. It was the way he wrote to me. Not at all like the style of the book, which is very dense. As he says, he stopped believing in many of the things he wrote in the book. In the 1990s he was involved in the Parallel Youniversity, which was like a salon in a rave, organized by the Zippie protagonist Fraser Clark. He was known as Cyber Geoff and he was, indeed, an early website designer. He used to go around with a toy lizard in his breast pocket. This was a reference to David Icke’s famous assertion that the world’s run by shape-shifting alien reptiles, the equivalent of the Dark Gods of his own earlier imagination. The lizard was meant to show that he no longer believed that. Lizards were nice, he said. He also said that the Illuminati, the villains both in Icke’s mythology, and in The Dark Gods, may have been the good guys, not the bad guys.

The reason I decided to read it is that I wanted to check if there was anything malign in the book. Gilbertson claimed he had a breakdown after he finished writing it, but his serious breakdown, the one that caused him to become infantilized and that sent his vocal tone into the stratosphere, came years later, in the 2000s rather than the 1980s. Friends told me that he never ate properly, living off snacks and microwave meals. He had Irritable Bowel Syndrome and had to rush to the toilet frequently. He was also always in love with some woman or another, many of whom would take him for a ride, rip him off and then dump him. He was a vulnerable person who never knew how to look after himself properly.

Despite its ponderous writing style, the book is very dark and paranoid. It’s relentlessly Manichaean, positing an eternal battle between good and evil, between the agents of the light and darkness. It’s full of references to death and suicide and to people being driven mad. On one page Roberts states that it’s easier to be evil than to be good, while Gilbertson, in his introduction, refers to the book as “an excursion into what some might call ‘a peculiar form of madness’.” It’s also obvious that it’s Roberts who’s leading the argument. His literary voice is more accomplished than Gilbertson’s, and, in fact, there are a number of titles that bear his name. He died in 1990 and I’ve been unable to find any biographical details about him.

The Geoff Gilbertson that I knew was a holy innocent rather than an agent of the dark. Everyone I spoke to about him commented on the sweetness of his character. It’s odd that he chose to take part in writing such a darkly obsessive book, but it’s clear that he would’ve had his breakdown anyway, whether he wrote it or not. He was such a fragile person, not designed to live easily in our fractured world.

—Follow Chris Stone on Twitter: @ChrisJamesStone