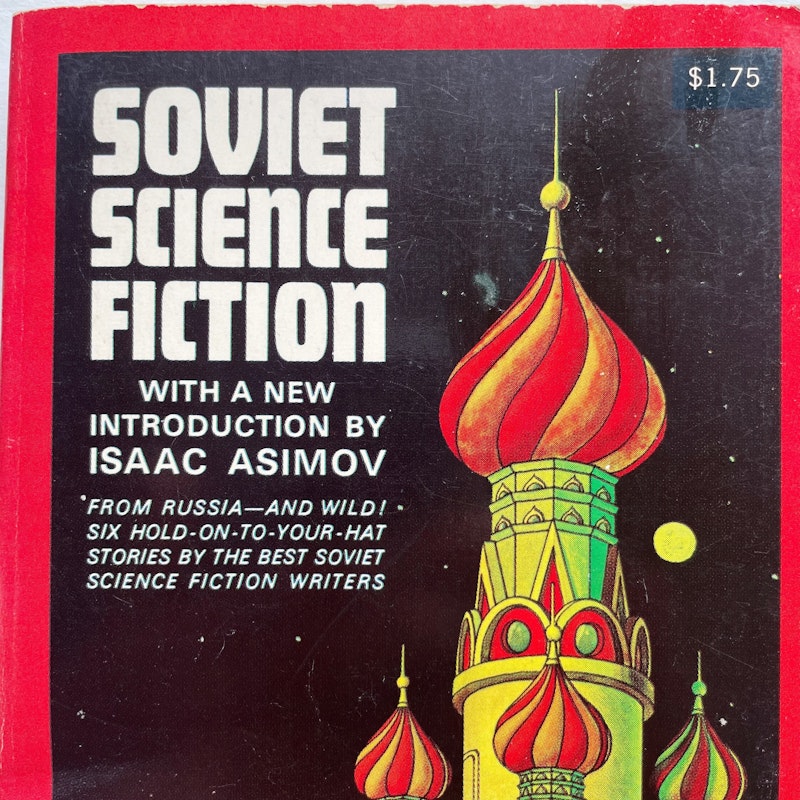

After months of stretching myself thin on writing projects, I’ve recently blocked time out for, let’s call it, “off-topic” reading. I’m trying to branch out my science fiction consumption from excessive amounts of Philip K. Dick—too much of whom I can’t imagine is good for my sanity or my prose, as much of his body of work was poorly-written until he’d really crossed over the acid-threshold of the 1970s. I’ve accrued some Soviet sci-fi collections, in part because of my renewed interest in Eastern Bloc film. I chose the first collection, aptly named Soviet Science Fiction, because it was one of the first collections of Soviet sci-fi short stories published in the US in 1962. The collection is notable for only two things: 1) an expository introduction by Isaac Asimov, and 2) being kind of bad.

Asimov, the Russian-born author, lays out a narrative that in the Western World science fiction is seen as largely an American phenomenon, something that readers of Hugo Gernsback magazines wouldn’t question—after all, their consumptive habits are American. Asimov deftly denies this as a universal phenomenon between Blocs, of course the Soviets of the day aren’t going to American authors to look for ideas about the future! He mentions an unnamed “Soviet literary publication” that has itself cherry-picked examples from American sci-fi specifically to denounce it “militarist, racist, and fascist,” which he believes an incorrect read of his contemporary literary climate (although looking at “Golden Age” sci-fi with a modern eye I’d disagree with Asimov’s opinion). Yet in order to make Soviet sci-fi palatable to American audiences, the editors of this publication choose to go for the most toothless stories. Asimov admits as much in the intro, saying the editors avoided what would have too much anti-American or anti-capitalist sentiment. Perhaps this was to avoid the spread of “propaganda,” however what it does instead is reinforce an idea that the Soviets are distinctly behind-the-times literarily.

There are three stages (up to the then-present) that Asimov posits for the development of science fiction literature:

Stage One (1926-1938)—adventure dominant

Stage Two (1938-1950)—technology dominant

Stage Three (1950- ? )—sociology dominant

American literature, naturally, is in “Stage Three,” while Asimov believes that the Soviets are trapped in “Stage Two.” It’s an interesting theory, although his structure, like so many harebrained sociologists, is imposed rather than innate. Why should science fiction literature necessarily progress from technologic speculation to narratives about societal developments? Are they necessarily separate?

More than his introduction is enlightening about Soviet literature, it’s revealing of Asimov’s own beliefs about what science fiction should be rather than what it is. As far as I can tell, since the collection's original publication in 1962, the Asimov introduction has always been included. This is almost a decade after Asimov completed his original Foundation series, books which extrapolate the decline and fall of the Roman Empire into a space-age narrative. They have a very necessary idea of history, where events progress in such a logical manner that all of time can be predicted by “psychohistorians.” It would make sense, then, that Asimov would believe that all societies and cultures have a path so specific that it could be mapped out—and that these maps all work the same.

Literature is literature, and so it progresses like literature. Different conclusions about the future aren’t much more than aberrations. It’s a denial of reality, presenting another world’s stories in their least otherworldly manner possible. It’s strange for someone self-declared as concerned about sociology would argue: while Fukuyama would argue that opposing forces to liberal capitalism (fascism and communism) that ceased to exist, Asimov’s idea of necessary development implies that the difference between these ideologies are all merely window dressing without their own structural forms. Despite saying that he’s interested in ideas of progression, Asimov’s imposition really implies that there’s no such thing as history at all.